The Numbers Are In, And They Add Up To A Low Chance Of Major Hurricanes In The Gulf In 2015

Spring is almost at an end. And the world’s hurricane experts have finally quit crunching the mountains of data about what weather systems did to the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the winter and the early days of spring. They’re finally able to give those on the eastern coastal regions of the U.S. their first notions of what might happen this hurricane season.

Let’s do as we always do in the Lagniappe hurricane forecast story and start with the grand-daddies of hurricane forecasting — the ones who started it all more than 30 years ago: the meteorological researchers at Colorado State University.

If you put your faith in the folks at Colorado State, you won’t spend an undue amount of time worrying about hurricanes this season. Those scholars are predicting that 2015 will be one of the least active hurricane seasons of the last half century.

In its April prediction, Colorado State’s likelihood of a major hurricane — that is, a of a storm ranking 3-5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale — striking somewhere along the Gulf Coast this fall is only 15 percent. That’s exactly half the statistical average for the last century.

The situation is identical for the east coast of the Atlantic (including peninsular Florida) — a 15 percent chance of a strike in 2015 as compared to a 30 percent chance on average.

Colorado State calls for only three hurricanes total, and only seven named storms, in 2015. The historical averages are 6.5 hurricanes and 12 named storms per year.

The chances of a major hurricane tracking into the Caribbean this year are only 22 percent. Again, that’s well below the historical average of 42 percent.

As one might expect, this year Colorado State has particularly encouraging predictions for regional areas. Chances of a major hurricane striking regional hot spots are all well under one percent, with the chances ranging from a high of .6 percent in Cameron to a low of .1 in Orange. Across the board, these percentages are half of the historical averages. That is, in any given year, there is a 1.2 percent chance of a hurricane striking Cameron Parish. This year, you get to cut that number in half.

Why Such A Mild Season?

As always, a lot of the hurricane story boils down to what big wind will be active come fall.

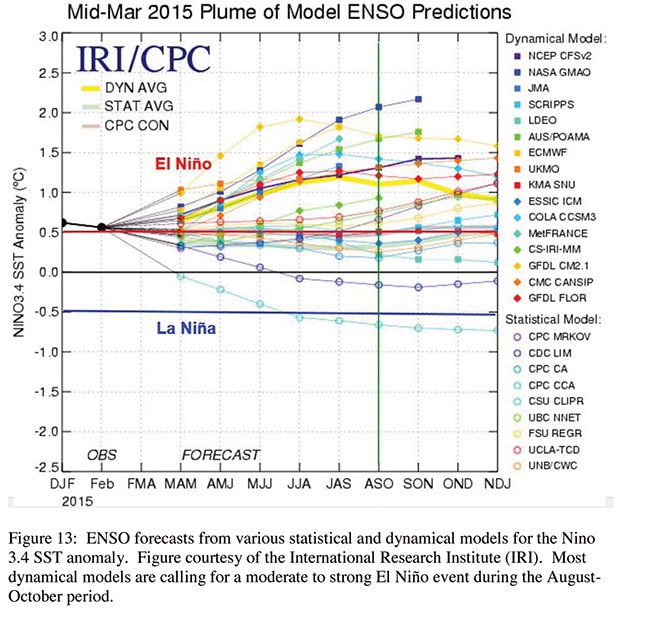

This year, says Colorado State, the El Niño current will dominate the summer and fall. The university researchers say that El Niño will exercise “at least a moderate influence.” NOAA says there is a 60 percent chance that El Niño will dominate the hurricane season.

In March, almost all major European forecasters predicted an El Niño season. El Niño winds discourage development of hurricanes in the Atlantic.

As you can see in the graphics included with this story, the major European forecasters have been even more emphatic about predicting an El Niño season. Depending on which data set you choose, only one or two is predicting the possibility of a dominant La Niña.

In general, it is felt there is a strong correlation between El Niño influence and weak storm development in the Atlantic.

Water temperatures, say the Colorado State forecasters, are already indicating a slow season.

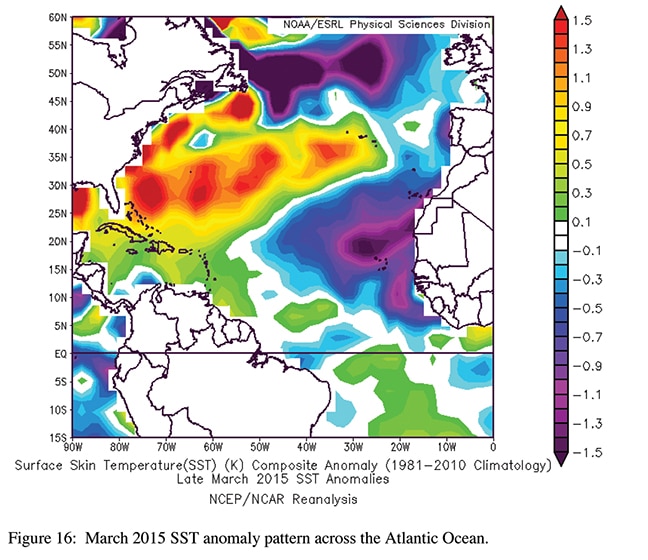

As of April, water temperatures in both the subtropical and tropical Atlantic, say the scholars, are “quite cool.” When these waters stay cool on into the late summer and early fall weeks, the Atlantic has much less of the warm, humid air it needs to form major storms.

For those who want to dive in and get the details, let’s look a little closer at the exact reasons the folks in Colorado think our storm season will be pretty tranquil this time around.

Our Story Begins In March …

Who knows when the long story behind the August and September storm season really starts? Certainly the conditions that will bring storms in the Indian summer are well underway in the Atlantic Ocean in March.

This March, sea surface pressure in the subtropical Atlantic was high, and that meant that Atlantic trade winds were high. These high trade winds mixed and blended the waters of the subtropical Atlantic, keeping them unusually cool. (It may help you to place the subtropical Atlantic if you remember that both Lake Charles and the Florida panhandle are in the subtropical zone.)

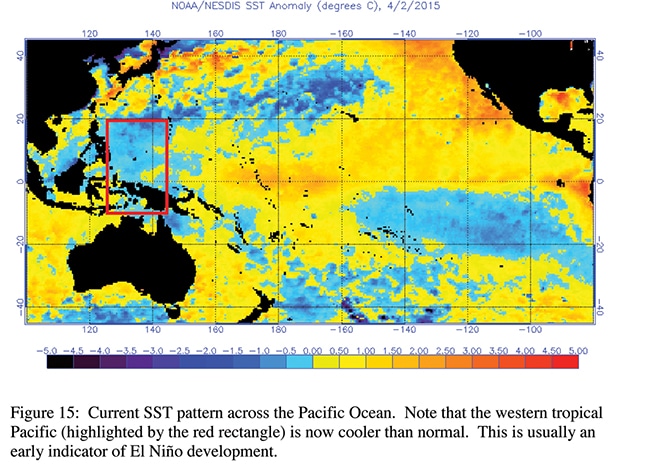

Notice that the waters of the western Pacific are extremely cool. If westerly winds continue to prevail, cool waters will move to the central Pacific. This reduces the development of tropical cyclones in the Gulf

If the waters in the Atlantic storm basin stay cool, they won’t contribute the rising, hot humidity that develops into big storms and hurricanes.

Now … back to March, 2015. In this month, sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean soared. While this was going on, the strongest westerly wind in the Pacific since 1997 developed.

Westerly winds are a key factor in El Niño development. Strong westerly winds move the hot air of the western Pacific to the eastern part of the ocean, where the waters are cooler.

If these waters in the eastern pacific stay cool, the number of cyclones that develop right on the other side of Central America in the Atlantic will usually be low.

As you can see in the graphic provided at the top of the opposing page, the water temperatures in the far west Pacific were quite cool in March. If the Westerlies and the corresponding water movements continue, this cool water will eventually move into the central Pacific. That drop in water temperature would put a real damper on cyclones that are fueled by Pacific heat and humidity and eventually turn into big storms in the Gulf.

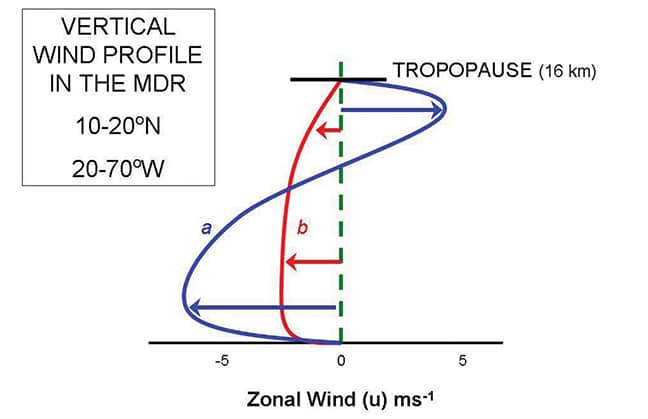

One major effect of a dominant El Niño is the increase of wind sheer in the Atlantic storm basin. With a lively wind sheer, winds near the surface of the ocean tend to stay brisk and be driven by a great deal of movement. These active winds break up storms before they can develop into hurricanes.

Finally — again, in March — the surface temperatures of the part of the Atlantic off the coast of Africa were extremely cool. This factor also points to a low number of hurricanes in the Atlantic this fall.

Most of the hurricanes that come our way originate in the waters off the west coast of Africa. Cool waters here significantly reduce the chance of the development of major storms that may one day become hurricanes in the Gulf or off the east coast of the U.S.

Reasons For Skepticism?

Colorado State has beaten the average in 23 of the last 33 years. To put it in terms of percentage, the University has beaten the average 70 percent of the time. Whether those numbers are good enough to earn your credence in hurricane forecasts is, of course, your decision.

There are still plenty of doubters when it comes to hurricane forecasting. And in fact, the reservations that Colorado State offers about its own forecasts are pretty daunting. When one forecasts hurricanes, says Colorado State, “one is dealing with a very complicated atmospheric-oceanic system that is highly non-linear … No one can completely understand the full complexity of the atmosphere-ocean system.”

Wind shear: The blue line (a) shows the extremely active wind shear that’s associated with low hurricane activity. The active winds tend to blow apart storms before they can turn into hurricanes. Winds like those in the blue line will be around this fall due to the influence of El Niño

The university goes on to note that the situation is further complicated by the fact that the Atlantic storm basin has more weather variance than any other storm basin in the world.

We remember that in 2005, Colorado State erred when it underestimated the number of big hurricanes and south Louisiana was devastated by Katrina and Rita. A similar off-year took place in 2013, when a year that was supposed to be active turned out to be flat (with the exception of one major hurricane that made landfall).

But the university admitted to its mistake; scholars there said deviations in 2013 were due to “massive changes in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic that occurred after the issuance” of the forecast.

Others agree that Colorado State caught a bad break in 2013. Todd Crawford, chief meteorologist of Weather Services International, says, “By most measures, 2013 was one of the strangest years in the tropical Atlantic in many decades.”

In spite of Colorado State’s 70 percent success rate, some leaders in the field aren’t quite ready to jump on the hurricane forecasting train just yet. For instance, while the Weather Channel does predict the number of hurricanes that will form in the Atlantic Ocean each year, it still declines to predict how many of these hurricanes will strike U.S. coasts.

Moderate Outlook All Over

Let’s look at what the Weather Channel is predicting in terms of hurricane formation in the Atlantic Ocean this summer and fall and compare those predictions to some by other big players.

The Weather Channel:

— 9 named storms

— 5 hurricanes

— 1 major hurricane

Tropical Storm Risk (a prediction group in London getting a lot of press):

— 11 named storms

— 5 hurricanes

— 2 major hurricanes

Colorado State University:

— 7 named storms

— 3 hurricanes

— 1 major hurricane.

You’ll notice that while all the predictions are conservative, Colorado State is calling for a considerably milder season than the other two.

A Brief Historical Note

Colorado State’s Bill Gray, who started the whole hurricane prediction phenomenon in 1984, is retiring from the project this year. Although, he says, he’ll still be coming into the office and working on the data every day, his interests in climate change and global warming have increased to the point that he will now make these subjects the focus of his research.

He will, he says, continue to act as an advisor to the hurricane prediction team.

Note the extremely cool water temperatures off the coast of Africa. This is where most storms that eventually hit the Gulf coast originate. Cool waters in the north Atlantic and warm waters along the U.S. east coast are also associated with low hurricane development.

Future teams will be headed by Phil Klotzbach, who has been working with Gray since 2000, first as a graduate student.

The Disclaimer Stills Applies

Every hurricane forecaster delivers the same disclaimer every year: no matter how small the odds of a hurricane striking on your land, if one strikes, it will be overwhelming and perhaps deadly. Consider that Hurricane Aubrey destroyed Cameron in an El Niño season. That was very much an aberration, of course. But if there’s one thing that’s certain, it’s that the weather sometimes sends aberrations our way.

Because there is always at least some possibility of a strike, when it is hurricane season, check in regularly with your favorite meteorologist or weather web site. If you can, get email weather alerts from a reliable source (such as NOAA, for example) or get a weather app and follow it. Use a tracking chart if you have time to.

Know local evacuation routes; the moment you feel that evacuation is called for, get started. If you can afford to do it, have accommodations booked out of harm’s way even if you think an evacuation won’t be necessary.

You’ll find other helpful tips for preparation for storm season throughout this special hurricane section. As all of us in Southwest Louisiana know, you can never have too many batteries, candles and matches, or too much water. Best of luck.

Comments are closed.