Most discussion of our soaring fed-eral debt (now more than $28 trillion) is focused on financial issues such as how much debt is too much for a country (it is now 110 percent of our GDP); how can we ever pay it back (it is equivalent to $226,000 per taxpayer); or what would happen if the interest the federal government had to pay to borrow increased (interest on the debt is currently the third largest item in the federal budget). But there is another aspect to the federal budget deficit that has generally been over-looked, and that is how it affects our federal form of government.

When I was in high school back in the 1960s, I recall seeing a diagram in my civics textbook showing how our government is structured. It was a pyramid with the federal government at the top, state government below it and at the bottom, municipal government. When I got to college and read our Constitution, I was surprised to discover that is not at all how our federal system of government works.

According to the enumerated powers clause of the Constitution, the national government and the state governments are co-equals, but have different areas of responsibility. The federal government is responsible for things like national defense, foreign relations, coining money (but not printing paper money), borrow-ing from foreign governments, providing the framework for commerce among the states (such as postal service and patent rights) and ensuring the free flow of goods and labor across state lines.

Subsequent amendments to the Constitution and Supreme Court deci-sions have expanded some of these pow-ers (for example, bank robbery and kid-napping were made federal crimes so criminals could not simply step across a state line to avoid arrest).

Thus the power of Congress and the national government is limited, and all functions not delegated to the federal government in the Constitution are the responsibility of the individual states. (Municipal government is not mentioned in the Constitution, so city governments are created and regulated by the states.)

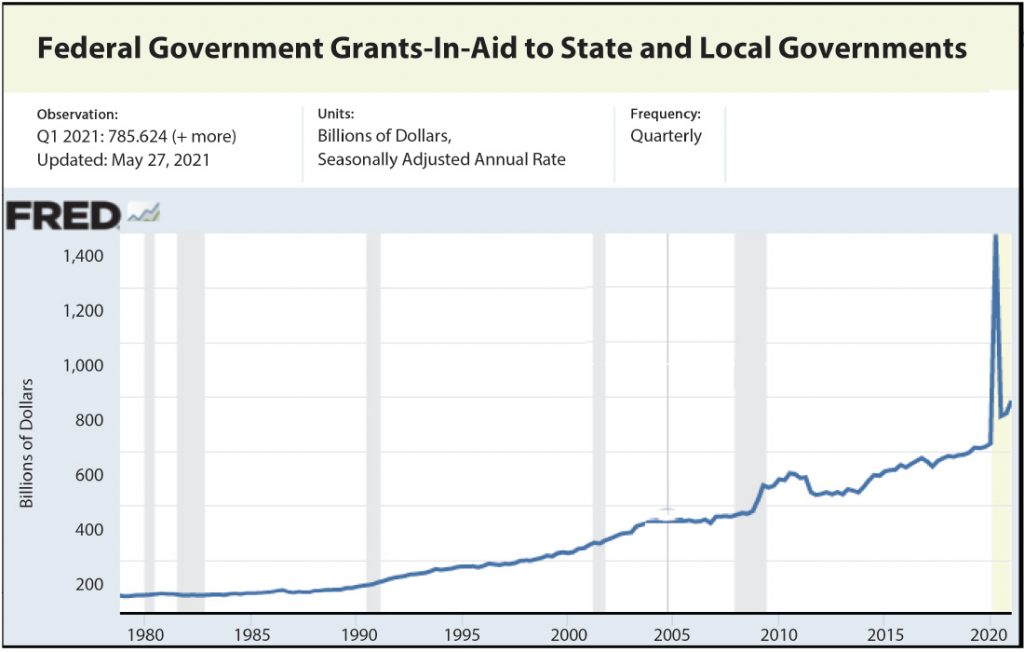

But over the last 50 years, the federal government has increasingly encroached on state and local government affairs. The primary way it has done this is by offer-ing money to state and local governments (called “intergovernmental transfers of funds”). But it has done this with strings attached: “If you want this money, then you must accept our conditions.”

For example, during the 1974 OPEC oil embargo, Congress passed the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act. The intent was to conserve gasoline by making people drive slower. So Congress prohibited speed limits higher than 55 miles per hour.

Congress had no constitutional authority to regulate speed limits, and rural states such as Nevada objected because it made no sense to putt across the desert on a deserted highway at 55 miles per hour. But if these states wanted federal funds to maintain their highways, they had to play by Washington’s rules.

And as the amount of intergovernmental grants from the federal government increased, so did the rules and regulations Congress could impose on states and cities (see Graph 1).

What does this have to do with the federal debt? Among the enumerated powers of the federal government are those of coining money and borrowing on the credit of the United States. So when the federal government has a budget deficit, it cannot simply print money to pay its bills, but it can borrow money by selling bonds. That is why Congress created the Federal Reserve Banking system in 1917. “The Fed” prints our paper money. (Take out a dollar bill and look at it; it is a “federal reserve note,” and it even tells you which of the 12 federal reserve banks issued it.)

Contrary to what many people think, the Federal Reserve is not a government agency, which is why it does not have to comply with the “sunshine laws” and can conduct its business in secret. And while Congress appoints the chairman of the Fed, it cannot fire the chairman because he or she is not a government employee.

Initially the Fed was required to have silver or gold in reserve to back the paper money it printed. These were called silver certificates. They stated that they could be presented at a federal reserve bank and exchanged for silver. But this changed in 1971 when, due to the need to borrow to finance the Vietnam War, Congress decided the Fed could hold government bonds to back our currency because promissory notes of the U.S. government are “good as gold.” So, the way it works now is that when the federal government runs a deficit and must sell bonds to pay its bills, the Fed can simply print the money to buy the bonds. Of course, pumping all that money into the economy will cause inflation and drive up interest rates, which is exactly what happened throughout the ‘70s.

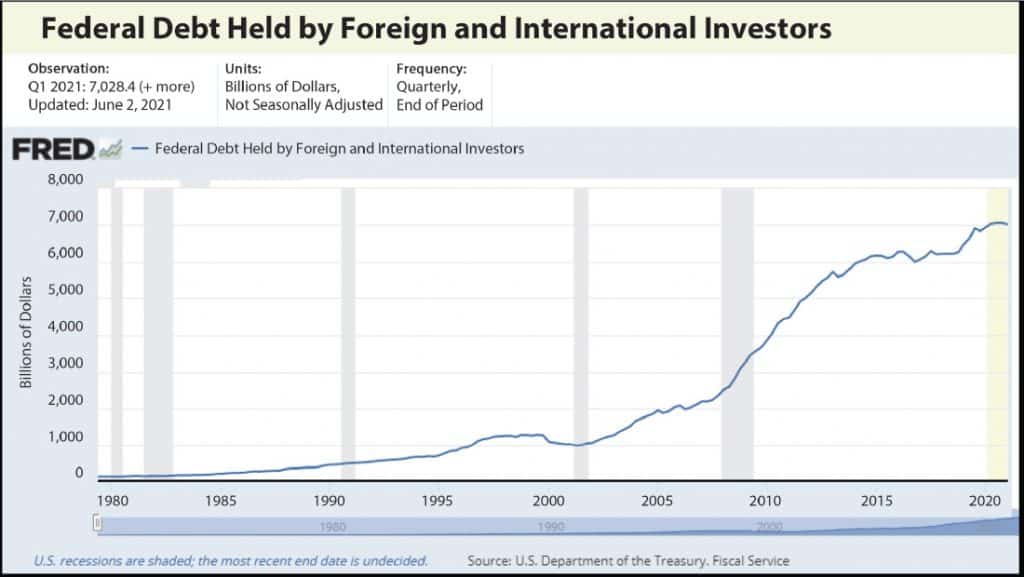

Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980 and the Fed changed its policy and began limiting money creation to keep inflation around 2 percent annually. Nonetheless, Congress kept on spending and selling bonds to cover its budget deficits. At the time, the consensus among economists was that all this borrowing by the federal government was going to drive interest rates up and crowd out private investment, but that did not happen. Something new was going on. In the past, most of the government bonds were pri-marily purchased by U.S. citizens. So in a sense, “we owed it to ourselves.” But a global bond market had developed, and increasingly our government bonds were being bought by foreign interests (see Graph 2, above).government employee.

That was great news for Washington politicians because it meant they could keep on spending without raising taxes or creating inflation or driving up interest rates that crowded out private investment. In other words, there appeared to be no adverse consequences to their spending so long as foreigners were buying their bonds. (Well, there was one consequence. The money used to buy our bonds could not be used to buy our products, so we be-gan running large trade deficits. But that did not seem to bother Washington; they just blamed it on bad trade deals.) Getting back to how borrowing from foreign interests affects our federal system of government, there was now a spending and borrowing imbalance be-tween the federal and state governments. State governments cannot run deficits that the Fed will monetize by printing money; they can sell bonds, but their bonds have the same standing in the bond market as those of any private business. So, free money from the federal government is extremely attractive to states, even with all the strings attached. If it seems the federal government has its fingers in every aspect of our lives, intergovernmental transfers financed by foreign borrowing is how Washington gets it foot in the door.

Comments are closed.