My last Lagniappe column was about our federal system of government. To briefly sum it up, state governments in the U.S. are not under the federal government. Article I of the U.S. constitution lists the functions assigned to the federal government in general. They are things that require the collective action by all the states such as national defense, foreign relations and international commerce, with all other powers left to the individual states. Yet, over the last 70 years the federal bureaucracy has managed to extend its fingers into just about every aspect of our lives. How did this come about?

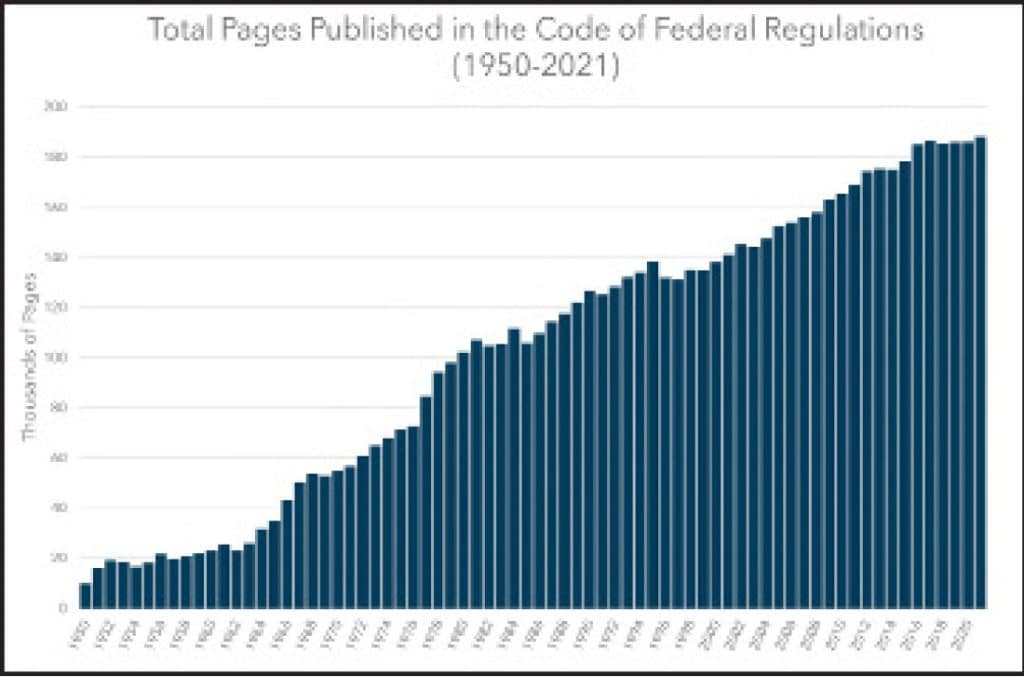

But the number of employees may not be the best measure of the scope of the federal bureaucracy. Table 1 shows the number of pages in the Code of Federal Regulations which has grown from 10,000 in 1950 to 185,000 in 2020.

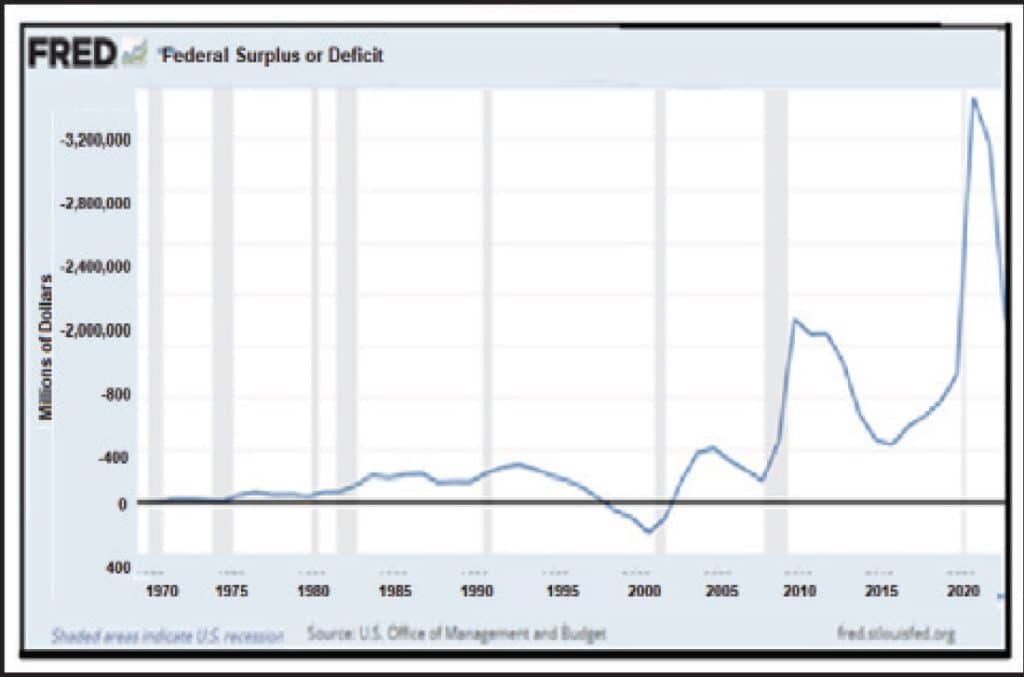

It is my contention that the growth of the federal bureaucracy has been fueled by two developments: deficit spending by Congress (see Table 2) and intergovernmental transfers to state and local governments (see Table 3).

Here is how it works. Back in 1956, President Eisenhower signed into law the National Defense Highway Act, the largest public works project in American history. The act envisioned a network of interstate highways modeled on the German autobahn constructed by the Nazis before World War II.

National defense is a legitimate function of the federal government, but the interstate highway system affected much more than the military. These highways had a huge impact on communities they connected or bypassed, as well as the U.S. auto industry, and our oil and gas dependency.

Another example of federal intrusion is education. Education is not listed in the constitution as a function of the federal government, yet there is a cabinet-level department of education. How did that happen?

Back in 1957, the Soviet Union shocked the world when it successfully launched “Sputnik,” the world’s first orbiting satellite. According to U.S. Senate records (senate.gov), “on the day Sputnik first orbited the earth, the chief clerk of the Senate’s Education and Labor Committee, Stewart McClure, sent a memo to his chairman, Alabama Democrat Lister Hill, reminding him that during the last three Congresses the Senate had passed legislation for federal funding of education, but that all of those bills had died in the House. Perhaps if they called the education bill a defense bill, they might get it enacted. Senator Hill, a former Democratic whip and a savvy legislative tactician, seized upon on the idea.”

A cry went out that the U.S. was losing the “space race” because our schools were inferior to Russian schools, so Congress began pumping money into what is now called STEM education under the National Defense Education Act.

So, what did we get for the federal aid congress poured into STEM education? The National Science Board tracks student performance on standardized tests in science and math in different countries. The U.S. now ranks 37th, and our scores have not improved in over a decade. Meanwhile our universities and industries must look overseas to find qualified professors and technicians, while many of our college graduates are unable to repay their federal student loans because they opted for easy classes not in demand in the job market.

These early federal programs were achieved by labeling them as defense acts. But the rapid growth of the federal bureaucracy came after the federal government gained the ability to spend without taxing (i.e., deficit spending). This happened in 1971 when the U.S. went off the gold standard. The dollar was grossly over-valued at $28 per once of gold (today it takes $2,000 to buy an ounce of gold), so we went to a free-floating currency, where the value of the dollar is measured in terms of other world currencies. For Congress, this meant budget deficits did not have to be backed by gold, now the Federal Reserve could simply “monetize” the deficit by buying the government bonds. To our politicians in Congress, this appeared to be “free” money.

Congress has a self-imposed debt ceiling, but every time they reach that ceiling, they simply vote to raise it. It is like the alcoholic who takes out another credit card to pay their bar tab. The federal government is now more than $31 trillion dollars in debt, which is 20 percent more than our annual production of goods and services. In the fourth quarter of 2022 alone the interest on the federal debt was $213 billion, up $63 billion from a year ago.

Most commentary on the federal debt focuses on its fiscal impact with scant attention paid to its impact on federalism and the growth of the federal bureaucracy. But while Congress can spend without taxing, the states cannot do the same: if a state runs a deficit, it must back up its borrowing with a revenue stream, which alters the balance of power between the federal and state governments.

The federal government cannot force a state to do anything that is not within its enumerated powers listed in the Constitution, but it can bribe their way in. If a state wants to spend without taxing its own citizens, it can invite the federal government in to assist them with spending — say for disaster relief, food stamps (SNAP), medical care, free school lunches, environmental concerns, unemployment benefits, economic development — it can turn to Congress for the federal funds. But like the 55-mile-per-hour speed limit, federal money always come with strings attached.

Comments are closed.