By Brad Goins

If you want to keep tabs on local flooding, you can’t have an office that’s better suited than mine, with its big window that opens onto Common Street a block south of College. The intersection of College and Common is notorious for it ability to collect flood waters.

The events of May 17 reminded us all that the reputation of College and Common is well-deserved.

I went through that intersection about 7 am on the 17th. Rains had been heavy through much of the night, but I felt they’d slacked up enough that I might be able to sneak in a trip to the office.

Once I was seated at my desk, it wasn’t long until the downpours returned. After some time, Common Street was covered with rain water. I paid no mind to it. That sort of thing isn’t all that unusual.

Somehow I missed the fact that there was something unusual about this particular rainfall. I didn’t pick up on any extraordinary intensity or duration. But after a while, I did pick up on the extent of the flooding. And something about that was way out of whack.

It must have been about 11 am when the water on Common Street could no longer be contained by the road and began to creep up over the sidewalks and into the yards. At first, drivers didn’t seem to be extremely concerned. A steady stream of vehicles — including small sedans — chugged through the waters. As any lucid person would have expected, at some point, vehicles began to stall. What was interesting to me was that when that point was reached, pickups and SUVs stalled almost as often as sedans.

I began to think that Lake Charles might have a serious problem on its hands. I checked Mayor Nic Hunter’s Facebook on a regular basis. He had posted a short eulogy for the just-deceased Gov. Buddy Roemer. And each time I checked the page, that’s what I saw. While I’m sure that some in the Lake Area felt a twinge of loss for Roemer, at some point the populace must have begun to feel a need for other words.

As the water level continued to rise, I checked both the City of Lake Charles website and the Mayor’s Action Hotline page. There was no hint that anything out of the ordinary was going on.

Someone in the office tuned into the end of KPLC-TV’s lunchtime news broadcast by means of her cell phone. When the noon broadcast ended at 12:30 pm, the anchor informed viewers that the station would have news again at 4 pm. I didn’t get the sense that an unusually significant event was being reported. The announcer did say several times that people should not be driving and that vehicles created waves that flooded homes.

At one point, I said to my office mate, “There’s a major national story going on here and no one’s reporting it.” That exuberant remark was probably just an expression of the nervous tension I was feeling. But I do think that, to some extent, anyway, I realized the tremendous scale of what was happening.

Meanwhile, the National Weather Service reported “this is a particularly dangerous situation.” (And, the service used all caps to emphasize the last three words in quotes.)

By the end of the lunch hour, the water had spread so far that every lawn, driveway and parking lot visible from my office was underwater. I had never seen anything like it. The extent of the flooding was so obvious that people actually stopped driving through the water for 20 minutes or so.

But then the driving started again, and it never stopped. It was to be a long, slow afternoon and evening of bad behavior. There was, at most, a five-minute gap between the pickups that moved through the water — some travelling at a brisk rate. Sometimes the drivers travelled in convoys of three or four. Few of these trucks were driven by workers. The only loads in most of the truck beds were human loads. The drivers of a good half of these trucks were sightseeing.

In one truck bed there sat a man in his 30s, swiveling his head in fascination as if he were a 5-year-old attending his first class in school. At the end of one 20-foot-long truck, another man, who had lowered the tailgate, leaned down out over the churning colossus. I couldn’t imagine why he’d put himself in such a dangerous and unnecessary position.

In many pickup cabs, the person in the passenger seat stuck a cell phone out the window to film the flood waters. In other pickups, the passenger just pushed his body through the open window and rubbernecked the scene.

Of course, each of these pickups created huge waves that pushed flood waters further and further into houses that lined the road. And some had their vehicles flooded by truck-generated waves. Waves from traveling pickups knocked down a large wooden replacement fence that had been erected after Laura in the yard north of the office.

By 4 pm, I was the only one still in the office building. All I had learned from media sites and press releases was that the sheriff’s department was swamped with calls, the garbage collection had been cancelled and the flood warning was still in effect. The voice of authority spoke in whispers.

Although it never stopped raining (as far as I could tell), at a certain point the waters did begin to subside a bit. At a glacially slow rate, the process of drainage began to gain on the process of flooding.

After hours, I lay on the office couch, pondering the options of spending the night in the workplace or walking home through the floodwaters. At 6:30, I decided to run the risk for the comfort of my own bed.

While it wasn’t any fun to walk across the intersection of Common and College, the water wasn’t as deep as it had seemed to me. After I made it through, I noticed that only the very bottom of my cargo shorts was wet.

Nothing at the intersection indicated that there was any reason not to drive through it. There was no warning sign; no sign stating that the intersection was closed; no flashing lights; no presence of law enforcement or other government employees.

I wouldn’t have imagined that deeper water awaited me on Hodges Street. Of course, I couldn’t see the sidewalk as I walked. But I worked hard to ensure that I did keep my feet on the sidewalk. I didn’t know how deep the water might go if I stepped off the pavement. I think at this point, the water must have gone at least halfway up my thighs.

I actually got stuck in foot traffic behind some dude who’d chosen to slow down and have a leisurely cell phone conversation right in the middle of a flood. I thought about going around him and passing him, but I dared not step off the sidewalk.

When I got to Alamo Street, I could see that something big had happened there. People had quit driving for one thing. Both sides of the road were lined with the vehicles of drivers who’d pulled off and parked. It must have been an ungodly mass of water that was capable of getting the sightseers off the road.

When I crossed Alamo, all my flood-related problems magically disappeared. On Hodges Street north of Alamo, it was just another day. There was no flooding; no pooling of water; nothing but a clear path. Whatever was happening in the blocks of Hodges north of Alamo, it looked like a solution.

Beseeching The Weather

After I got home and showered off the muck, I enjoyed a good night’s rest. As I lay in bed at 7 am the next morning, trying to decide whether I should risk a trip into work, it occurred to me to check the mayor’s Facebook page. The latest entry was still the eulogy to Roemer.

I saw that KPLC had finally gotten to the meat of the matter, having posted a story with the headline “Many drivers stranded after all-day deluge in Lake Charles.” But I had to scroll quite a ways down the web page before I got to the story. I didn’t understand why it wasn’t a big banner headline at the very top of the page. When I checked the site again at 11 am, the story had moved even further down the page. We can hardly blame national media for failing to highlight our news when we don’t highlight it ourselves.

For the KPLC story, Teresa Schmidt interviewed a driver who’d found herself stuck in the parking lot of Walgreens. Schmidt quoted the stranded driver as saying, “I think it’s crazy. I think we’ve been through enough in the past year …” “Apparently the weather failed to get the memo that it has been too hard on Lake Charles and needs to ease up a little.

Some time after I arrived at work, I learned that the American Press had published a free edition that carried the simple banner headline “SW La. inundated.” Someone had finally grasped the magnitude of my big national story.

The notion that beleaguered locals have the ability to control the type of weather that arises surfaced in the Press story, which included this quote: “’Mother Nature needs a Chill Pill,’ said Lois Parker in a Facebook post.”

Sometime during the previous afternoon, Hunter had been interviewed by the American Press. Although the Kroger “Weekly Ad” that kept popping up made it a real challenge to read the story, I did manage to glean a few points that were of interest.

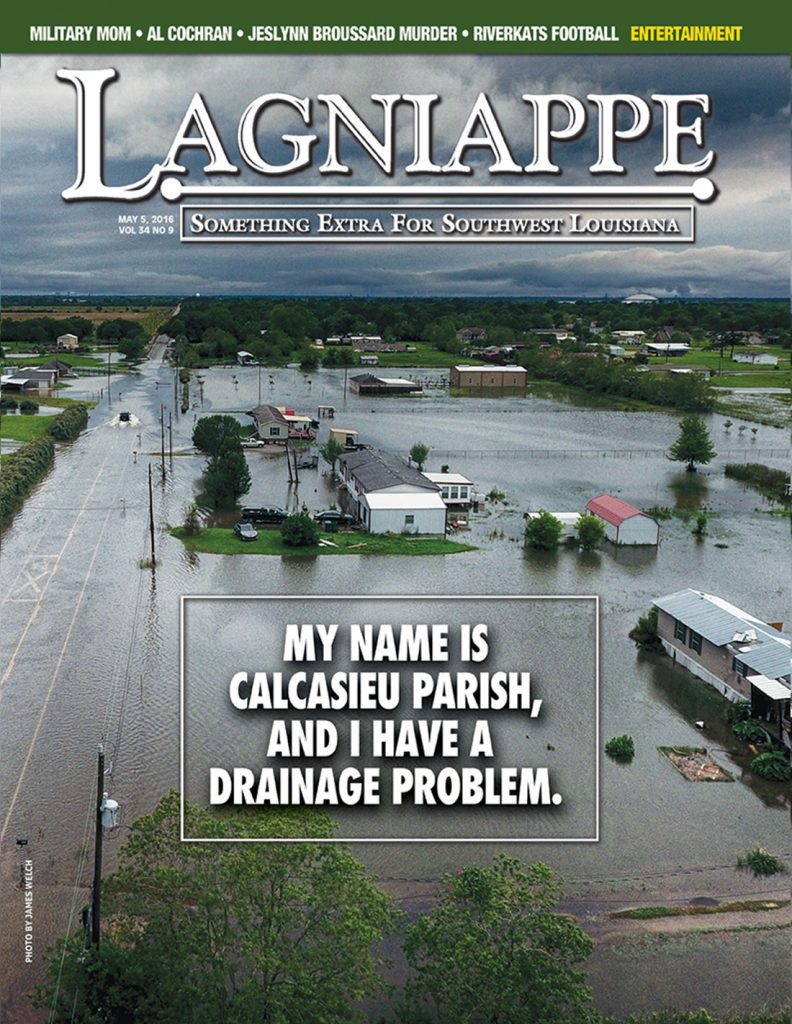

“If we had $1 billion in the bank, [the drainage problem] could not be solved overnight,” Hunter said. “This is not something the city or the parish can solve alone. It’s going to take a community effort.”

He pointed out that debris left over from Hurricanes Laura and Delta could be blocking drains.

After work, I made my usual evening perusal of the Washington Post. And it was then that I saw it. The big national event I thought I’d sensed was being reported in a big national story. The Post feature carried this headline: “Flash flood emergencies in Louisiana while double-digit rainfall deluges Texas.” But what was doubtless of more interest to people around here was the subhead: “Lake Charles, ravaged by two hurricanes last year, had its third wettest day on record Monday. More excessive rain is forecast.”

Readers were informed that rainfall rates in Lake Charles “topped three inches per hour.” The official total rainfall was 12 1/2 inches. But one rain gauge south of the city recorded 15 inches.

The Post reported that Monday, May 17 was the “third wettest calendar day on record in Lake Charles” — a wetter day than the area had seen with Hurricanes Laura, Delta, Rita and Ike. (The top two rainfall totals, said the Post, were 15.67 inches on May 16, 1980 and 15.79 inches on June 19, 1947.)

A video that accompanied the story showed a father paddling a kayak down Common Street as he went to pick up his children from school.

Nic Hunter told the Post “he’d talked with federal disaster officials who said they could not think of another city that has been subject to as many federal disasters in a similar time period [that is, less than a year].” The Post paraphrased Hunter as saying that Lake Charles “is still waiting for a supplemental disaster relief package from Washington to help the region recover from Hurricane Laura …” And the Post quoted him as saying, “The plight of the average homeowner in Lake Charles is unthinkable at this moment. You have people that are possibly ripping out Sheetrock and renovating a home for the third time. The financial capability of this city, the human capital that we have here, is finite.”

He estimated that 400 to 500 structure had flooded on May 17.

All of that practical information was followed by a personal appeal to Mother Nature: “You know, eventually you do kind of get to a point where you ask Mother Nature: What more can you do to us?”

As you may have noticed, this odd trope of talking as if we alter the weather of the future by appealing or complaining to the weather was prominent in media reports. In addition to Hunter’s striking notion of “asking Mother Nature” about something, there was this from the American Press’ John Guidroz on Twitter:

“After Monday’s historic flood, I think Lake Charles’ new motto should be ‘We can’t catch a break’ or ‘Can we catch a break?’ I saw it posted all over social media yesterday.”

I was pleased by practical comments from Sheriff Tony Mancuso, in which he refrained from making any personal appeals to the weather: “I wish I knew what to say to our citizens right now to give them some encouragement because they’ve been through so much the last year. Just hang in there.” Sounded like pretty good common sense advice to me.

I later learned that at about the same time the Washington Post published its story about the Lake Charles flood, the New York Times ran a story that carried this headline: “A Deluge Unleashes Floods in a Louisiana City Still Reeling from 2 Hurricanes.”

National media is starting to pick up on the fact that Lake Charles has been battered by the weather. Indeed, coverage has been so extensive that President Biden was inspired to pick up the phone and call Nic Hunter on May 20. And of course, Mayor Hunter is perfectly correct. We need to see those federal aid dollars pouring in.

Down To Cases

Longtime local resident Brad Buller was especially concerned about the flooding around the area where Alexander Lane intersects with Ham Reid Road. “There was just so much stuff floating” in the water — boards, trash cans, weeds. It took the water several days to subside. Buller says there continues to be a great deal of debris on Alexander Street near Ham Reid.

An 18-inch culvert pipe (smaller than the 3-feet culvert seen in parts of Alexander Lane) seemed to be an especially bad spot for blockage. Buller suspected the pipe might be too small for the job and might be clogged by something that didn’t look as if it was going to be removed any time soon.

Buller thinks another factor that may have contributed to the extensive flooding is the abundance of new construction near the area. There’s a new Circle K, roundabout and new subdivisions, among other projects. All that construction creates parking lots and other structures that cover large areas with vast stretches of flat concrete. Rainwater has nowhere to go but roads and ditches. “In the past,” says Buller, the site of the new construction “was just a big field.”

Buller had no problems with flooding before Delta. But that hurricane brought 3 inches of water into his house. He put in new flooring, 6-inch base boards and Sheetrock. Then the flood on May 17 brought in 7 inches of water. All the new construction had to be ripped out. He says he’s “basically starting over.”

Delta was the start of an ongoing drainage headache. After Delta, he said, the “ditches would fill and the water wouldn’t move … It’s like that everywhere south of town.”

So, What Happened To The Weather?

So what happened to the weather to bring about the phenomenal results of May 17? “Everything just set up well” for an extended application of rain from the Gulf of Mexico. That’s the prognosis of Andy Patrick, the National Weather Service meteorologist in charge of Lake Charles.

Patrick says that Lake Charles is part of what he calls the North Gulf Coast, which runs from Houston to the Florida panhandle. The area is “very susceptible to high rainfalls … They just set up over a certain area.”

Part of the set-up is the process of banding. Banding is what soaked Lake Charles on May 17. Banding creates “a narrow band of rain with huge rainfall rates … The southern part of the band just keeps moving north [out of the Gulf].”

The band is so narrow it actually appears to take up only a small area on radar. Rainfall rates in the band can be two to three times as heavy as those of the typical spring or fall storm. Because the band is so narrow, towns just 10 miles to the east or west may get relatively little rain. Such a band ran right over Lake Charles on May 17.

This sort of banding and near paralysis of rainy storm systems is particular to the North Gulf Coast. It’s not something that happens on the East Coast.

The May 17 flood “is not really all that surprising to me,” says Patrick. Something similar “happens a lot during tropical systems such as Harvey,” which dumped a record 56 inches of rain on Galveston as well as 54 inches in Houston. “It could happen in Alexandria or Baton Rouge,” says Patrick. (Some will remember that in the famous August, 2016 flood, East Baton Rouge got more than 20 inches of rain in three days; Brownsfields took on 27 inches and Watson was hit with 31.)

Of course, what Lake Charles experienced on May 17 was not a tropical storm. Patrick says it was “more of an intense spring storm system.” Without the distinctive Gulf Coast banding, it could have been a typical spring cold front. (The 2016 Baton Rouge storm was also just a regular storm fed by very slow-moving rains coming in off the Gulf.)

So, while the degree of flooding that Lake Charles experienced on May 17 was extremely rare, in the end, it was perfectly consistent with the weather patterns of the area.

Comments are closed.