Experts Say The 2021 Hurricanes Will Be Active, But Nothing Like 2020

By Brad Goins

After Hurricane Delta became the second super-storm to batter the Lake Area within two months, folks around here found themselves wondering whether the 2020 hurricane season was more active than the monster season of 2005, which brought Louisiana Hurricanes Rita and Katrina.

The expert opinion on the matter wasn’t even close. As far as meteorologists are concerned, 2020 was the hurricane season from hell.

The season broke records left and right. When Hurricane Delta hit in October, 2020, it was the 10th tropical cyclone to make landfall in the United States in the season. That broke the old record set in 1916.

When subtropical storm Theta was named on Nov. 10, 2020, that set a new record of 28 named storms in a season (surpassing the previous record, which was set in 2005).

After Theta, one more named storm remained: the colossal beast Iota, which became a Category 5 hurricane and blasted Pearl Lagoon, Nicaragua, with 155-mph winds, doing its worst just 15 miles from the place where Hurricane Eta had wrought devastation 13 days earlier.

The 2020 season brought with it 14 hurricanes and 6 major hurricanes (hurricanes between Categories 3 to 5; in May, 2021, NOAA revised its statistics about Hurricane Zeta, bumping it up from Category 2 to 3). A total of 11 named storms made landfall in the U.S.; that was another new record. (The previous record was set in 1917, when 9 named storms hit the American coast.)

September, 2020, was the single most active storm month in recorded weather history. It produced 10 named storms. On September 18, three storms were named in a single day.

When Hurricane Zeta made landfall Oct. 28, it became the fifth named storm to make landfall in Louisiana in a single season. That set a new state record.

In a NOAA press release issued on Nov. 11, 2020, NOAA Weather Service director Louis Uccellinni said he had not expected to see another hurricane season as active as that of 2005 in the remainder of his career.

It was only the second time in history that Greek letters were used to name hurricanes because the entire English alphabet had been exhausted. (In March of this year, the World Meteorological Organization announced that Greek letters would no longer be used to name storms. In the future, a second list of 26 English proper names will be employed.)

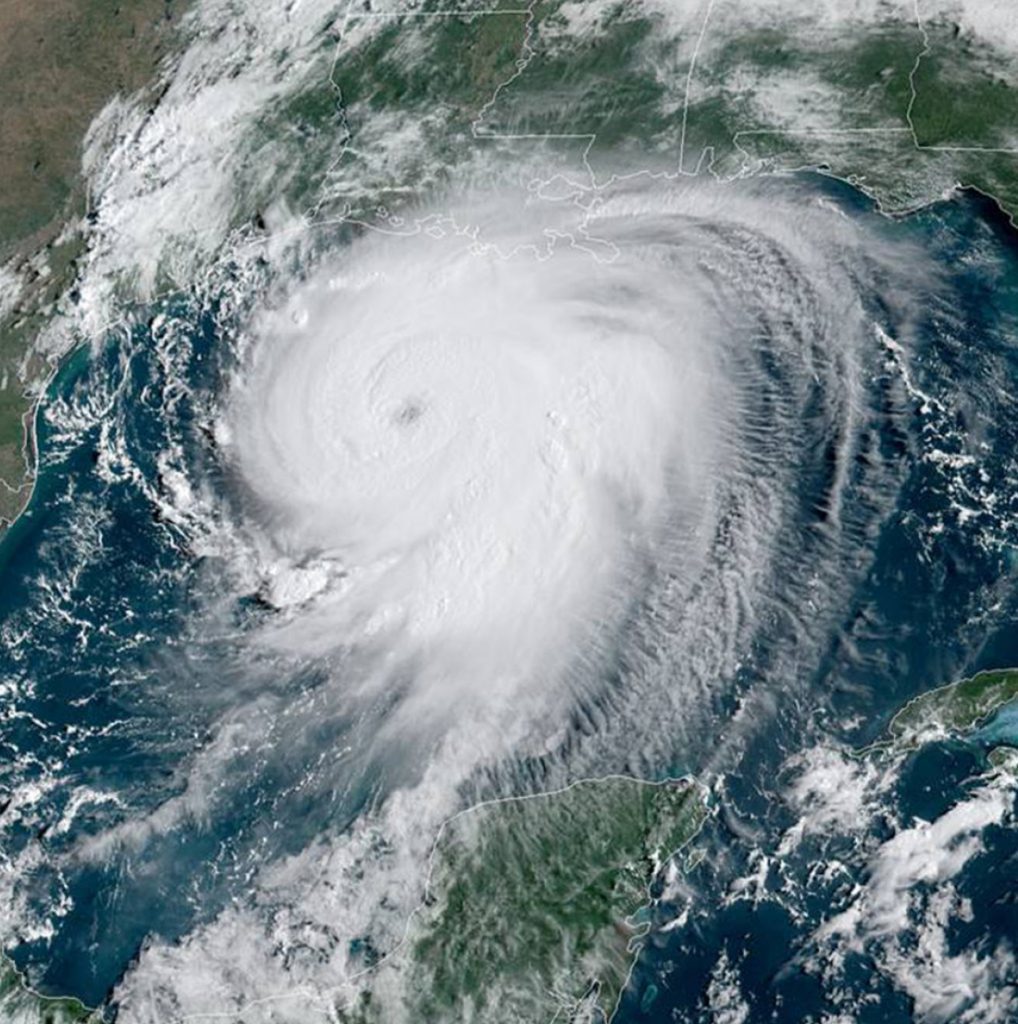

And Then There Was Laura

The centerpiece of the record-shattering season was Hurricane Laura, which reached the speed of 154 miles an hour in Holly Beach. That was a tad above the speed of Louisiana’s previous record hurricane: the Last Island Hurricane of 1856. (See the story on that storm elsewhere in this issue.)

How did Laura rank in comparison with other record hurricanes? Yale University Climate’s Connections ranked Laura the fifth strongest hurricane to make landfall in the U.S. But the group noted that its ranking was based on the Saffir-Simpson scale, and that scale does not measure storm surge. Laura’s storm surge surpassed 20 feet at Rutherford Beach (and exceeded 17 feet in parts of Lake Charles). This storm surge was surpassed only by the totals of more than 25 feet that were notched by Hurricanes Katrina and Camille.

There was also the question of the significance of one site being slammed by two hurricanes in one season. While such a thing is highly unusual, it’s not unheard of.

In 2004, Hutchinson Island in Florida was hit by Hurricane Francis on Sept. 5 and Hurricane Jeanne on Sept. 26. When Hurricanes Fay and Gonzalo hit Bermuda in 2014, they made landfall just six days apart.

As for why Louisiana was a magnet for storms in 2020, Ben Schott, head meteorologist at the National Weather Service New Orleans office said, “It’s just bad luck. I hate to say it that way, but it’s true. I can’t give you a scientific reason …”

Big Changes

For meteorologists, the 2020 season was a clarion call. It would fundamentally alter the way in which we see hurricane season.

One way we know this is that 2021 saw unprecedented changes in the procedures used in NOAA’s hurricane division.

In February, 2021, NOAA announced that the beginning of its tropical storm season would be pushed forward from June 1 to May 15. (NOAA was no doubt well aware that in 2020, the Lake Area had been on the watch for tropical storm Arthur, which was named on May 16, and Bertha, which was named May 27. The 2020 season was the sixth consecutive season in which a named storm developed before June 1.)

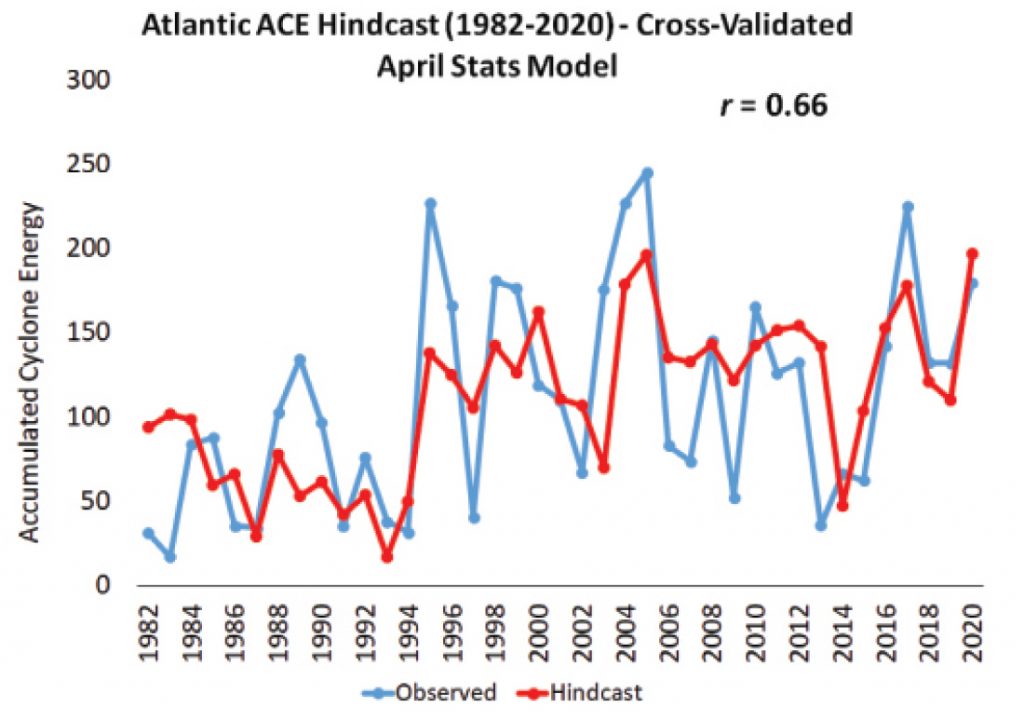

CSU’s hurricane prediction record. The red line shows the weather that was predicted and the blue line shows what actually occurred.

While the official starting date of the hurricane season didn’t change, NOAA said it was seriously thinking of releasing its hurricane predictions at an earlier date.

As of April of this year, the official NOAA averages for hurricane season were revised upwards to 14 named storms and 7 hurricanes per season. That marked an increase from the earlier averages of 12 named storms and 6 hurricanes.

Matt Rosencrans, seasonal hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, said that the new, more negative, average reflects “our collective experience of the past 10 years, which included some very active hurricane seasons.”

The reference to the last 10 years was an acknowledgement of the increasing severity of storms. It resonated with a statement made by Lake Charles Mayor Nic Hunter at about the same time in which he pointed out that Lake Charles has been the site of 10 federally declared disasters in the last 10 years. Four of those disasters took place between March, 2020, and March, 2021. (And of course, the huge flood struck Lake Charles and other areas on May 17. As of press time, it had not become a federally declared disaster.)

As far as increasing severity goes, it’s also worth noting that in each of the last five hurricane seasons, a hurricane has hit Category 5 hurricane status before hitting the coast of the U.S.

On the other hand, Rosencrans’ choice of a 10-year period is somewhat curious given that NOAA adjusts its hurricane season average (if necessary) on the basis of the last 30 years of data. Thus, the new average reflects the hurricane data of 1991 to 2020. That data was skewed enough to boost the seasonal average from six hurricanes to seven. (The average number of major hurricanes — those that are Category 3 to 5 — did not change; it remains at 3 major hurricanes per season.)

The vast majority of hurricanes that strike the Gulf Coast originate in the Atlantic Ocean. NOAA did not change any seasonal averages for the Pacific Ocean.

After the new averages were announced, NPR reported that a key factor in the increased totals was ongoing increases in the surface temperature of the Gulf of Mexico. As the Gulf is more shallow than the Atlantic Ocean, its waters can more easily become hot and spawn major storms.

An ‘Above Average’ Season

So … does the hurricane season of 2021 have more weather horrors in store? On April 8, Colorado State University issued its first hurricane forecast for the 2021 season. Its prediction was for 8 hurricanes and 4 major hurricanes. This is a fair amount higher than the average for the last 30 years, which is 7.2 hurricanes and 3.2 major hurricanes.

Colorado State describes the predicted degree of activity as “above normal.” The research group is careful to note that it does not expect 2021 to be as active as 2020.

The CSU researchers predicted that the chance of at least one major hurricane making landfall on the Gulf Coast was 44 percent (in comparison with the overall average of 30 percent), and the chance of at least one major hurricane coming into the Caribbean was 58 percent (versus the average of 42 percent).

For nine coastal parishes in Louisiana, CSU predicted the chances of a major hurricane making landfall. Cameron Parish was said to have a 6 percent chance, which is a little high. However, Cameron’s 6 percent was lower than the percentages for the 8 other parishes. CSU said there was a 23 percent chance that some location in Louisiana would be struck by a major hurricane in 2021.

The Weather Channel also released its hurricane forecast in April, predicting 8 hurricanes. But it parted company from CSU in predicting that only 3 of those would be major.

When NOAA released its hurricane prediction on May 20, it was, interestingly enough, the most negative of the bunch. The agency called for an “above average” season with 6 to 10 hurricanes and 3 to 5 major hurricanes.

Why Above Average?

Why is an active season likely in 2021? For starters, there is a good chance the major wind system La Niña will dominate the eastern Pacific Ocean, just as it did during the whole storm season of 2020.

While CSU can’t guarantee this turn of events, they are placing their bets on it. “The odds of a significant El Niño [the opposite of La Niña] seem unlikely,” says the official report of the forecast. But those who prefer a less active storm season might find reason for hope in CSU’s assertion that “there remains considerable uncertainty as to whether the tropical Pacific will have [El Niño] conditions or continue to have La Niña conditions.” CSU’s reservation was echoed in an emphatic manner on May 13, when NOAA announced that La Niña was over and that there was a two-thirds chance of “neutral” conditions in the tropical Pacific throughout the summer. None of this, however, means that La Niña cannot return in the fall.

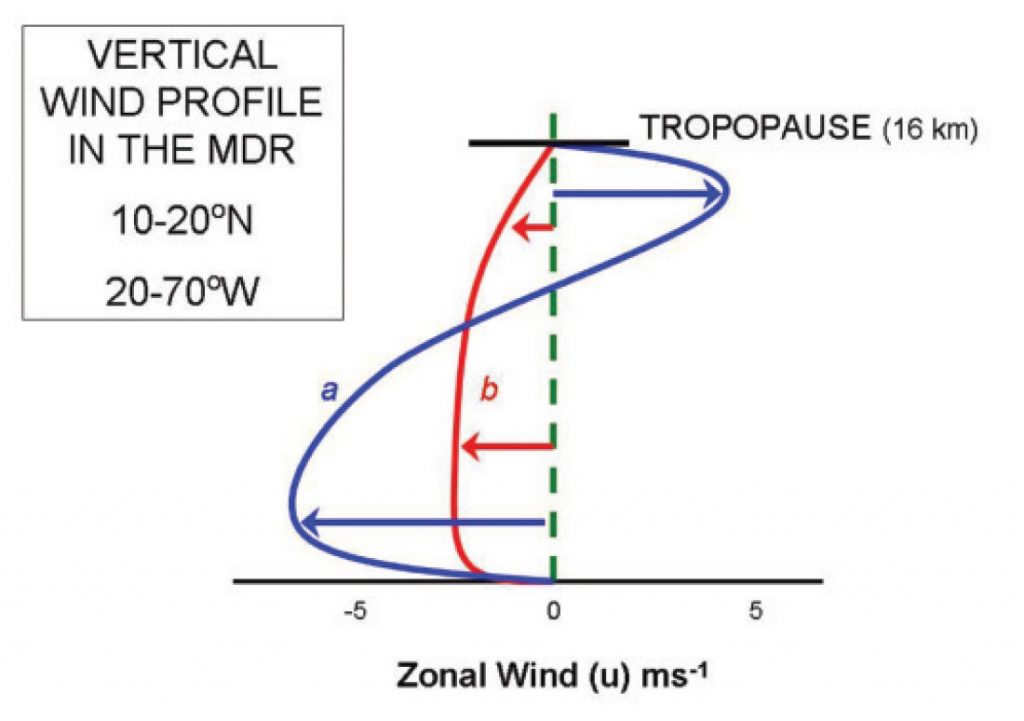

When La Niña is dominant in the tropical part of the Pacific Ocean, cool wind currents travel across the land and into the Gulf of Mexico. Because these currents are low — close to the surface of the water — they don’t create wind shear: strong vertical bursts of wind that rise up from the ocean and break up storms that are forming over the ocean’s surface.

Also increasing the chances for storms this season is the fact that much of the North Atlantic has sea surface temperatures that are above normal. That situation increases the chances of storm formation. Those temperatures were above normal throughout the 2020 season.

As is the case with all hurricane seasons, coastal residents are reminded by the Colorado State researchers that “it only takes one hurricane making landfall to make it an active season for them. They should prepare the same for every season, regardless of how much activity is predicted.” In other words, get your papers and pictures and meds ready to move quickly and stock up on that bottled water.

Comments are closed.