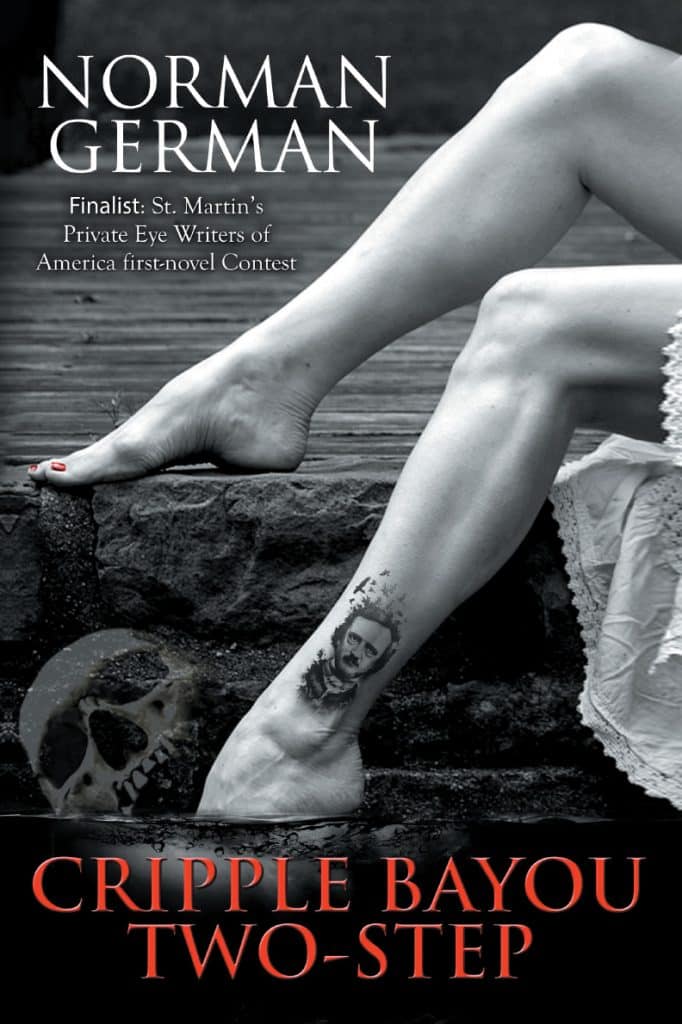

Cripple Bayou Two-Step: By Norman German

DVille Press, Donaldsonville, La., 2019. • 207 pp., paperback, $16.95

A Review By Brad Goins

Set in the Lake Charles of 1994, the protagonist of our mystery novel is Shreve West, who is one-handed and wears only t-shirts because he doesn’t need two hands to put them on. For the same reason, he wears Reeboks that fasten with Velcro.

Early in the story, we see that private investigator Shreve fits well in the tradition of the noir novel and the hard-boiled P.I. As he awakens from his sleep, he thinks, “the glowing red digits told me it was one in the afternoon, the earliest I had voluntarily gotten up in months. Even when I can’t sleep, I lie in bed till three or four staring at the dark, peaceful depths.” He has covered his windows with tin-foil.

Shreve’s surveillance jobs usually focus on three types of people: adulterers, dead beats and teenagers. He describes dead beats as “able-bodied men hunting and fishing or working on their camps, lifting lumber and chopping underbrush while back in town they’ve got some piss-ant junior lawyer filing workmen’s comp papers for them.” He videotapes them as they are working, then gives the tapes to the former employer. He likewise makes many videos of philandering husbands.

The Case

Shreve’s occupation changes quite a bit when it becomes clear Lake Charles has a serial killer at work in the city. Shreve’s assessment of the situation is strictly on point: “We don’t get serial killers in Lake Charles every day.”

The killer’s first two victims are found with a dead cat and frog (respectively) and a cigar. At first, the killer leaves very short notes in the animals’ mouths.

The third victim is King Eddy, a dwarf who is pretty heavily involved in shady activities in the less respectable venues in town. He is killed by morphine. The dead animal left with him is a blackbird, and the note reads “An ordinary person couldn’t get it.”

With the fourth victim, the killer moves to the upper class, choosing a victim who’s the son of two doctors. Jason Talber is poisoned with cyanide. He’s left with no dead animal, but, rather, with a blue glass eye, and a note that reads, “Here’s looking at you kid.”

Victim five is a man whose face has been cut up with a knife. The face is covered by a ceramic Mardi Gras mask. The dying victim had the strength to grab his telephone and write the word “TREEG” on his wall with his blood.

Shreve informs the reader that Brother Treeg has a church in the “back woods of Moss Bluff.” Brother Treeg tells Shreve that the victim had been at the most recent church service and had left with a female — one he didn’t arrive with. Shreve’s theory all along is that the killer is a female. He’s nicknamed her Mademoiselle Z.

Of course, not all of the book is about Shreve moving from victim to victim.

He spends much of his time courting a comely female college graduate who is many years his junior and works at a downtown Lake Charles coffee shop and restaurant. As he tells her the details about the murder victims, she points out that all the items left with each victim are found in some story by Edgar Allen Poe.

She’s greatly amused that he hasn’t noticed this himself. Shreve starts reading his Poe.

As a result of this discussion with his new, young girlfriend, Shreve knows the sixth victim was murdered by a copycat killer. This victim was female (the others were male) and was left with a Frisbee. There is, of course, no Frisbee in any Edgar Allen Poe story.

With victim seven, the corpse is left with a clock pendulum (for Poe’s story “The Pit and the Pendulum”). When Shreve sees the note left with this victim — “Now your time is running out” — he begins to think the murderer’s messages are referring to him and strongly suggest he will experience his demise in the not too distant future.

The feeling is intensified when the killer again chooses an upper class victim — bank president Junius K. Guillory. Writes German, “wedged into his heart is a brick layer’s trowel like the one in The Cask of Amontillado.”

The message left with this victim reads “Your reputation is on trowel.”

Any doubt Shreve might have that the serial killer is trying to target him disappears when he narrowly escapes an attempt to poison him in his home with cyanide gas.

Shreve’s Love Life

Moving in tandem with the progression of the criminal case is the progression of Shreve’s complicated love life.

After he’s struck up the affair with the voluptuous, young Debbie, the woman he really wanted years ago, Pixie — who is still in town — begins to send signals that she’d like to rekindle the relationship.

Thinks Shreve, “that must had taken some brass to flatten my heart, then burn it to a hard cinder and sail it like a roof tile into an abandoned field, and then call ten years later to ask me out and expect me to waltz back into her life with a bouquet of roses and a kiss at the front door.”

Nevertheless, he does eventually go back to the woman he once wanted to marry in spite of the fact that she has since been confined to a wheelchair with an extremely serious case of rheumatoid arthritis.

The analytical Shreve is honest with himself about the prospects of the relationship: “we had nothing to build on — no context, no ongoing jokes, no recent past.”

Still, this is the person he wants to be with. When he sees her, he is “nervous and happy and hurting all at the same time.”

Principles Of Investigation

One of the most fascinating aspects of the book is the set of tips about crime investigation that Shreve delivers here and there in the text.

Shreve makes much of the Locard Exchange Principle, which stipulates that “it is absolutely impossible for a criminal not to leave something at or take something away from a crime scene. There is therefore no such thing as the perfect murder, only imperfect investigations.” The principle first comes into play when Shreve’s bumbling police partner Brewton says about the first murder that the killer left no trace.

Probably of greatest interest are the three general principles Shreve says he has figured out from his years of experience:

“1. Always assume the worst.

“2. Suspect everybody. And I mean everybody.

“3. Third, rein in your ego … Pool your resources.” This basically means to be nice to law enforcement and all other potential sources of information.

Here’s another tip: “You don’t want to blow your cover. What if the guy you’re talking to is the murderer? Remember: suspect everybody, even if you’re looking for a hundred-pound girl.”

Shreve applies the principle with a man working the counter at a pawn shop. At the shop, Shreve sees a knife that he knows to be a murder weapon or an exact replica. But he acts uninterested. He nonchalantly asks the clerk a couple of cursory questions about how he got the knife, then calmly leaves the store. “Don’t spook him,” Shreve thinks. “You can always come back for details.”

And there is this observation: “Only the unimaginative would ever get bored in this business. It’s a vocation that gives you time to think and soul-search.” Shreve is perfectly content to sit still, stare into space and let his brain work.

Local Culture

There is a good helping of local culture in the book. One character uses the common statement of SWLA dialect “I’ve been knowing.”

There are also many references to places that might have existed in the Southwest Louisiana of 1994. “The old Paramount Theater” and the “First Marine National Bank” are likely candidates. I’m not sure about places such as the Gulf Breeze restaurant, Sweet Emma’s and Jacque’s.

Shreve courts his college graduate in the Coughing Cup coffee shop in the northeast corner of the Charleston Hotel. He says the wide-ranging clientele includes everyone from “refined lawyers to businessmen to college students and crack dancers.”

While Trosclair’s Barn may have been a creation of German’s imagination, the directions sure sound specific; it’s “downstream from Jacque’s on Cripple Bayou across the 210-bypass from Omsted’s Shipyard.”

Cast Of Characters

If the book has a shortcoming, it is that too many characters have been eliminated as suspects by the end of the story. Shreve presents a host of fascinating characters in the beginning of the book: thugs, prostitutes, dwarves, homeless addicts. But these characters are dropped after their roles in the beginning.

The only characters who are developed in fairly great detail throughout the book are medical examiner Dr. Vickers; Brewton; Poe Prof. Hobson Lynch; the girlfriend Becky and her roommate Denise and Pixie. During the course of the narrative, both Brewton and Lynch are arrested for the murder and then cleared. Pixie could only be a viable suspect if she is faking her arthritis. By the end of the tale, the number of possible suspects is getting pretty sparse.

Shreve starts thinking the chief of police (whose character has not been greatly developed during the book) may be the murderer. “Chief [Samantha] Ivy [known as ‘Poison Ivy’]?” he thinks. “Surely not.”

Finally, Shreve tries to turn himself in for the murders. He’s concluded he must have committed them in some sort of amnesiac state. After all, everyone else, he thinks, has been eliminated. He’s told to go home and get a good rest.

The story might have benefitted if more characters had been developed throughout the book so that there were more viable suspects at the end. About halfway through the book, I detected a clue that caused me to choose one character as the suspect. I guessed right. This didn’t make the story any less interesting for me. But if you’re looking for a book in which a gaggle of suspects is gathered together at the end and grilled, this is not that book.

The Human Condition

As in all his works, German makes many accurate and poignant observations about the human condition.

At one point, he breaks society into three classes: “those at the top,” “bottom feeders” and “then … those in the middle, people who, with a few breaks or a few setbacks, are poised in socioeconomic limbo to go either way — people like you or me.”

When Becky’s heavy friend Arleena Wilkins spends an entire year getting in shape to get rid of fat, Shreve again exercises his class consciousness when he thinks, “if you’re poor, you’re fat.”

After the seventh murder victim, Shreve begins to feel that he is very unlikely to solve the case. “He’s confused, lacking clarity, feeling adrift when he has lost his dignity and self-esteem and purpose in life — in short … he is depressed.” He has been a somewhat somber character throughout, and at this moment, he becomes Everyman.

No less philosophical is Poe Prof. Lynch when he realizes the murderer is probably planning to target him. “‘Vaht if I had died when I was zirty or forty or sixty?’” German writes. “He looked at me with a twinkle in his rheumy eyes and then he winked. ‘I mean, vaht de hell difference would it haff made?’”

This novel is perhaps not written with quite as much care as all of German’s works. German told me he only wrote the book at the prompting of his agent, who wanted to use this novel to promote another book with excellent prospects. Still, Cripple Bayou Two-Step is an outstanding read. It will keep you intrigued about one thing or another from beginning to end.

Comments are closed.