A Tale Of Too Many Children

By Kerri Cooke

“When a child of the streets stands before you in rags, with a tear-stained face, you cannot easily forget him. And yet, you are perplexed what to do. The human soul is difficult to interfere with. You hesitate how far you should go.” —Charles Loring Brace

Crises On New York Streets

It was not a good time to be a child in New York City during the 19th century. An influx of immigrants from across Europe compounded the problems of the poor. Often, the poverty people thought they were escaping from found them in their new home.

A shortage of jobs and housing often led to children living on the streets. Many children were orphaned due either to their parents dying on the journey to America or due to epidemics, such as yellow fever and typhoid. The diseases ran rampant within the close and unsanitary living quarters of the lower classes.

Other children were abandoned by parents who couldn’t afford to keep them. Some parents gave up their children to orphanages in hopes that they would have a better life. Children with less affectionate parents were left in the streets or given up on if they were sickly.

There were 30,000 children living on the streets in New York City in the 1850s. Many sold newspapers and matches to save themselves from starvation.

Street children, also referred to as street Arabs, often created gangs in order to protect themselves from assault.

Children, less savvy at navigating the rough streets, were arrested and put into prison with adults. The crime of surviving led to children as young as five being held behind bars.

If this seems like an eerie account straight out of Oliver Twist, that’s because poverty took the same shape in big cities across the globe. However, some sympathetic people observed the problems and tried to find ways to help.

The Beginning of The Orphan Train

A minister named Charles Loring Brace saw the need for reform, so he created the Children’s Aid Society in 1853.

At first, the society was a place where children could receive basic religious and academic training. Later, it became the first runaway shelter, christened the Newboys’ Lodging House. Boys were provided with room, board and rudimentary education. The number of children soon outgrew both projects, so Brace came up with a revolutionary idea.

His idea was to take the street children from New York City and send them to rural areas across the country for farmers to foster and adopt. This practice is now widely referred to as “orphan trains” but was known at the time by various names, such as the Emigration Department, the Home-Finding Department and the Department of Foster Care.

Brace believed in the goodwill of human beings. He concluded that farmers would welcome the help these children could bring and that the children would have their physical and emotional needs met in return. The arrangement would be beneficial for all parties involved.

Brace’s heart was in the right place when he created the Children’s Aid Society, but the issues he was seeking to rectify had no easy fix.

This system of shipping orphans to 45 states, Canada and Mexico was riddled with problems from the onset.

First, the term “orphan train” is misleading, as many of the children who were shipped around the country were not orphans at all — merely victims of poverty. Many children did not want to leave New York City, but were forced out anyway. And teenagers often became part of the orphan trains as a way to obtain a free ticket to a new life.

The first orphan train stopped in Dowagiac, Mich. It was led by E.P. Smith of the Children’s Aid Society. The children were shipped in cattle cars that were unsanitary, uncomfortable and inhumane.

Smith did not do things very properly. It was said he let passengers on the riverboat from Manhattan adopt a number of boys without checking for references. Regulations were supposed to require that prospective foster or adoptive parents provide references from a pastor and justice of the peace. The rule is thought to have been largely unenforced.

“Some orphan train children became notable public figures. Andrew Burke went

on to become the second governor of North Dakota.”

Smith took on board an additional boy that he had met at the Albany Railroad Yard. He never verified the child’s claim to being an orphan.

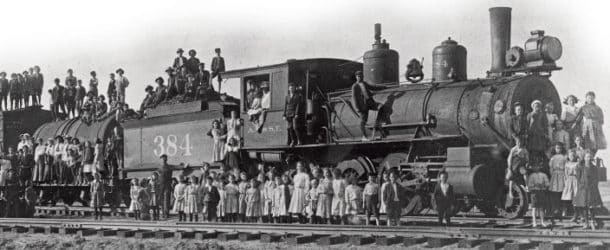

The convoy of children arrived in Michigan where they would be paraded before the public. People would have a chance to pick out what child they wanted.

Despite professionalism falling through the cracks, the first orphan train was considered such a success that two more were sent to Pennsylvania shortly after.

Children were provided with new clothes and a complementary Bible to take with them to their new homes.

Children would give their names, sing a song and tell a little about themselves while standing on a stage. This practice led to the creation of the phrase “up for adoption.”

Often, children were treated like animals. Locals would look them over, check their teeth and prod them.

Fostering or adopting a child was free of charge provided the child would help with chores. It was understood that the family was to treat the child as a blood relative, provide for their material needs and give them a sum of $100 when the child turned 21. The older children were to be taken on the understanding that they would be paid for their work.

The situation of the child was to be monitored by an agent visiting once time a year. In addition, each child was expected to write a letter to the Children’s Aid Society twice a year.

There were not enough workers to do a thorough job at monitoring. Also, the question remains how many children had or received enough education to be able to write to the society. Even if all the children could write, those who were abused could’ve been forced to pen what they were told or even have the letter written for them.

Many of the children on the orphan trains were white. Some attempts were made to place children with families similar to the ones they came from. For example, if a child spoke only German, then some attempts would be made to place the child with a German family. Sometimes this worked, but other times, children just went to whoever was convenient at the time.

As is the case today, babies were the easiest to place with a new family, since they were more easily integrated. Teenagers were the hardest to place because they were seen as stuck in their ways.

Perhaps the most difficult children of all to place were the disabled or sickly. Given that these children were seen as a liability, it makes sense that, unless a family was really trying to help, these would be the last ones to be chosen.

The society allowed for siblings to be separated. But, of course, it was ideal to be able to place them in a family together.

Another organization that sent children with the orphan trains was the New York Foundling Hospital. It was founded in 1868 by Sister Mary Irene Fitzgibbon.

The goal of the New York Foundling Hospital, since it was a religious institution, was to send children to be adopted by Catholic families.

It is estimated that 200,000 children were sent across the nation between 1854 and 1929. A lot of children never left New York as they were sent to rural families outside of the city. Other northeastern states — New Jersey, Connecticut and Pennsylvania—also received a large number of children.

One highly ironic fact is that Brace of the Children’s Aid Society didn’t send children to southern states at first. He was a staunch abolitionist. However, as we will see, many children were sent to homes where their status wasn’t much higher than that of a slave or an indentured servant.

Mail Order Children

The processes involved in providing these orphans or underprivileged children with new homes raises some questions.

First, how ethical was the process? Some children were taken away even though they had living relatives.

Second, children were sometimes ordered like a product out of a catalog. Potential parents could request the age of a child, their gender and eye, hair and skin tone.

Many families wanted children who looked similar to them. However, in the grand scheme of things, a child’s personality would seem to be more important than how attractive they might be perceived to be.

There was some controversy due to leaders coercing funds from the general public or getting people interested in taking a child by emphasizing the usefulness of the child. Boys were marketed as field laborers, while girls were pushed as domestic helpers. Child labor laws were not in place yet.

The question of whether these children were placed in good homes looms large. Many children were treated no better than servants. That was not the concept Brace was going for when he decided to try to re-locate impoverished children.

How many children were abused or molested as a result of this largely unregulated system? We will never know. There was obviously something very wrong as some slave owners complained about this new practice of obtaining children as a threat to slavery.

Better For Some

It would be incorrect to say that all the children’s experiences were bad and all adults looking for a child were in it primarily for ulterior motives.

The orphan trains were often a good opportunity for older couples or for couples who were unable to have kids to take in a child.

Many children were given a better life than they would otherwise have had. Children were saved from starvation, disease and who knows what else. Many orphan train children even went on to be highly successful.

Some orphan train children became notable public figures. Andrew Burke went on to become the second governor of North Dakota; and, a little closer to home, Joe Aillet became a football and basketball coach at Louisiana Tech in the mid-1900s.

Psychological Effects

Regardless of what kind of family these children were placed with, being a product of the orphan train left its indelible mark on their lives.

Children were generally very young when they were put into an orphanage or abandoned on the streets. Their formative years often were without warmth and human kindness.

Those who were abandoned by their parents often had an identity crisis. They didn’t know who they were, and were plagued with feelings of rejection.

These children, who already had a lot of hardship in their lives, were sent cross-country to people and places they didn’t know. Just imagine the fears in their little hearts and minds.

Their trials didn’t stop there, as they were often shunned by other children. They were disparaged — referred to as train children, outsiders, Yankees, orphans and thrown-away.

It was a widely-held belief that many of these children were from less than respectable families — maybe even the children of prostitutes and alcoholics. Children were encouraged to forget the past, and many lost contact with their blood relations if they still had any. Name changes often compounded the problem.

Louisiana Orphan Trains

Orphan Trains made stops in New Orleans, Morgan City, Lafayette, Opelousas and Mansura.

Often, children who came to live in Louisiana were more fortunate than others. Since many of them were requested by families beforehand, the chance of their being unwanted or claimed on a whim was smaller.

The children who came here were from the New York Foundling Hospital. Since Louisiana was primarily a Catholic state, the hospital saw Louisiana as an ideal location to settle the children.

While many children of the orphan trains did not like to talk about their experiences, there are a few people in Louisiana who told their stories.

The Louisiana Orphan Train Museum in Opelousas is responsible in a large part for obtaining information about the children who came to the state. They have records of 300 children, along with photos, documents and clothing.

In the spring of 1907, three orphan trains made their way to Opelousas. When the children descended from the trains, they had numbers attached to them that corresponded with their placement.

On May 7, 1907, George, 3, and Agnes Thomson, 6, arrived in Opelousas on an orphan train carrying 45 children. They were supposed to go to the same family.

A couple had requested a brother and a sister duo. Somehow there was a mix-up, and Agnes was sent home with George Murphy instead of her brother. She tried to inform the family of the mistake, but since they only spoke French, the message did not come across until it was too late.

The biological brother and sister met at a wedding before too long, but when Agnes tried to speak to George, he ran away.

Though Agnes and George didn’t live very far apart, it was over 50 years until they saw each other again.

Alice Kearns arrived on an orphan train in 1919. She settled into her new home in Erath with her foster parents. Her foster father took to her, but her foster mother treated her like nothing more than the help.

Alice Kearns Geoffroy Bernard became the last Louisiana orphan train rider before her death in 2015.

Sometimes a child arrived who did not meet a family’s written request. John Brown arrived in Grand Prairie to a family who had requested a male with black hair and dark eyes, but Brown had dirty blonde hair and blue eyes. Despite this discrepancy, the family kept and loved him as if he were just what they asked for.

There were orphan train children who were accepted into Lake Charles and Sulphur as well.

James Bray was one of these children. He was taken in by Rev. Hubert Cramers of Immaculate Conception Church in Lake Charles. He was raised with the help of the housekeeper, Mary Murphey.

The End Of Orphan Trains

The orphan trains ended in 1929. Some say the reason was because of the initiation of the modern day foster care system. Others say the prevalence of new laws restricting the movement of children across state lines were a main cause. However, there is another event in 1929 that I’m sure sealed the fate of the orphan trains more than any other.

The depression, undoubtedly, led to more children living on the street, so why would the orphan trains stop now? The answer probably comes down to money.

Wealthy donors would be more likely to hold onto their money now that the future was uncertain. In the absence of the funds that ran many public institutions, there would be even less for the poor.

Whether an orphan train child ended up having a better future or one that just extended their suffering was really up to fate. Regardless, every one of these children bore the mark of their past for the rest of their lives. They could rise to the heights of government or remain in poverty, but they would never escape their past. There was healing — never forgetting.

If you want to find more information about the Louisiana orphan trains, a book called From Cradle to Grave: Journey of the Louisiana Orphan Train Riders includes 89 biographies of orphan train riders.

The Louisiana Orphan Train Museum is open from 10 am-3 pm, Tue-Fri and from 10 am-2 pm on Sat at 828 E. Landry St. in Opelousas. The cost of admission is $5 for adults and $3 for children and seniors. For more information on the museum, call 945-4691 or visit laorphantrainmuseum.com.

Comments are closed.