A Story Of Second Chances And A Better Life

By Kerri Cooke

When people ask Elvis Martinez his name, often he has to take out his license to prove he is not joking. How many people do you know besides the “King of Rock and Roll” who are named Elvis?

Martinez certainly has the stamina, wit and personality to pull off such a name. But the most amazing thing about Martinez is not his name but his journey to becoming a permanent resident of the United States.

Growing Up In Honduras

Martinez grew up in Siguatepeque, Honduras, which he describes as a “small town like Lebleu or Iowa.” His parents were Rosario Cardona and Ruben Martinez. He had eight sisters and five brothers.

As most are in Central America, Martinez’s family was very poor. After the family house burned down when Martinez was 8, the family moved into a house with just two rooms. It had a dirt floor and no air conditioner. Martinez’s father built a kitchen for his wife outside of the house from bricks where she would bake bread to sell. The family also grew plantains, satsumas and mangos to sell in the city two hours away, San Pedro Sula.

Martinez’s father was a mechanic but started driving a taxi when the work did not provide enough money.

Martinez’s mother would buy each child two pairs of clothes and one pair of shoes for the whole year. If you messed those up, you didn’t get replacements.

Martinez began school at age 6. Starting at age 8, Martinez went with his mother to San Pedro Sula to sell bread. He also took the two-hour trip alone sometimes. He attended school until 6th grade.

Sickness Came To Stay

Martinez’s mother became sick with a kidney infection, and money was needed for her medication, so Martinez dropped out of school.

There was a rich lady in San Pedro Sula, Tina, who bought bread from him and offered him a job. So, at age 11, he moved to the city alone and promised his mother he would go see her every two weeks.

His workday began at 5 am and ended at 5 pm. He cleaned house, cleaned cars, dumped the trash, washed the dishes, fed the dogs and parrots and did anything and everything that had to be done. Martinez says it was really hard for a young child to do.

He resided in a little room outside the main house where he had a small TV and a shower that only spewed cold water.

Martinez made $75 every two weeks. He saved a little money for his bus fares and brought the rest of his earnings home to his mother on his bi-monthly visits.

Then one of his mother’s kidneys was removed in an operation. Unfortunately, it made her condition worse instead of better. The family wanted to get her a visa to go live with Martinez’s aunt in the U.S. so she could get better medical care. But she was too sick to travel.

As one of his duties for the rich family that employed him, Martinez left the house at 6 am to go buy bread at a shop five blocks from the house. Across from the bread shop was a body shop. Martinez asked the owner of the shop, Kevin, if he had some work because he needed more money to help pay for his mother’s medicine. He was told to go back to school. Martinez insisted he could learn bodywork.

He persisted every day until Kevin gave him a job. Martinez quit working for the people in the big house and worked at the body shop for $100 every two weeks. He was 12 at the time.

He worked at this shop for six months before a friend of the body shop owner, Eduardo Hernandez, hired him. He was now bringing in $125 every two weeks at 13 years of age.

During this period, Rosario Cardona asked Ruben Martinez to marry her before she died, and he agreed.

That day, Martinez says, his mother told him not to take her to the hospital anymore. She was tired of suffering and was sure she was going to heaven. Martinez describes her as a “really Christian woman.”

Martinez told his mom that if she died, he was going to go to America to help his brothers and sisters, but if she lived, he would stay. A week later, on a Thursday evening in Aug., 1996, Martinez’s cousin called. Rosario had passed away.

Martinez says he went crazy. His boss drove him the two hours to get back to his home. Rosario Martinez, 47, was buried two days later. Martinez says, “After that I was so lost.” This feeling compelled him into the next phase of his life.

The Trip To America

Shortly after his mother was buried, Martinez told his half-brother, Jeffrin Arriga, to pack his things because they were going to America. Arriga told him he was crazy, but Martinez insisted. He had promised his mom.

However, Martinez’s father was strongly against the plan, saying he would get himself killed.

After selling what they owned and with less than $50 in their pockets, Martinez, 13, and Arriga, 12, hugged their family goodbye and set out on the treacherous journey that would take them across rivers, through desert terrain and close to death before they reached the U.S. border.

The first step was to follow others headed to America. They passed through El Salvador, then through Guatemala, where they had to swim across their first river. By the time they got to Mexico, they had been walking and hitchhiking for a week and a half.

When in Mexico, they happened upon a boxcar train heading north. They ran, jumped, and hung onto the ladders on the outside of the train as others were doing.

Martinez and Arriga saw people fall to their deaths often as one by one people fell asleep and fell off of the train. So Martinez told Arriga to tie himself to the ladder with his belt in case he fell asleep. Martinez did likewise. The train didn’t stop for three days.

The train started going in another direction when they reached Querétaro, Mexico, so they got off. It had now been 20 days since they left home. They took a second train going north. This train brought them to Monterrey, Mexico.

Martinez and Arriga were with 15 other people, but got left behind after leaving the second train. They had no food or water and ended up in the Chihuahuan Desert.

Martinez and Arriga walked for three days and three nights alongside the railroad track. Eventually, Martinez had to carry Arriga because he was dying. They finally came upon a small community where Martinez begged for food and water from an elderly couple at 4 in the morning. Martinez and Arriga stayed at the house for two days to regain energy.

After that, they were picked up by an 18-wheeler driver whom they traveled with for a day and a half.

He dropped them off at the city closest to the Mexico and U.S. border — Ciudad Juárez. He couldn’t take them with him into America. But he said to tell the guards at the first checkpoint that they were his nephews. The boys did so, and, even though the guards didn’t believe them, they let them through anyway.

At this point, they were still on the Mexican side of the border. Arriga decided to go off on his own because, according to Martinez, “He wanted to smoke weed.” Martinez begged Arriga not to leave him, cried and used the arguments “you weren’t raised like that” and “I saved your life” but to no avail. Arriga left.

Then Martinez met a guy named Ramon who was selling fruit. He asked for a place to stay and make money for a little while before he tried to cross the border. Ramon took Martinez to his house where he was allowed to sleep outside on the roof. He stayed there for a week and a half.

Crossing The Border

A few times, Martinez tried to cross the border at the spot where everyone else was crossing. The border patrol would ask him where he was going and he would say Houston. They told him he was not from Houston, but replied, “Yes, I am.” They turned him back every time.

Martinez decided he would have to swim the Rio Grande in order to get over the border. Ramon told him not to do it. But Martinez, who had been swimming since age three, went ahead with his plan. He had made it this far. He had to help his family.

Many people have died trying to cross the Rio Grande because of the rip currents in the river. Martinez says many people make mistakes trying to cross. They try to swim against the current, tire themselves out and end up drowning.

He says he took off his clothes, put them in a bag he held by his teeth and swam catacorner across the river instead of straight. It took him 10 minutes.

When he stepped onto American soil a border patrol agent saw him through binoculars. But by the time the guard was able to get to the location, Martinez was gone. He had made it to El Paso, Texas.

Martinez asked people for some change so he could use a pay phone. He called his dad to let him know he was safe, and he called his sister in the states to come get him. However, he wasn’t in the clear yet.

He had to walk miles around the checkpoint and avoid cameras and the border patrol on 4-wheelers. He walked through rough terrain with cactus and thorns tearing up his feet because his shoes were falling apart. It took him four hours to go around the checkpoint.

Martinez says he was in bad shape after his 45-day trip that he estimates to be 5,000 to 6,000 miles long. He had blisters on his feet and weighed only 70 to 75 pounds.

But this boy had made it to the land of freedom alive.

However, he wasn’t free yet. He needed to become a legal citizen — a process that wasn’t and isn’t easy.

The American Dream

Martinez says that he wanted the American dream — to obtain citizenship, get married and have kids.

Martinez stayed at his sister’s house recovering for a while. He learned English by listening to people and asking what words meant and by watching TV in English with Spanish subtitles.

His first job was in a daqueria. He worked Monday through Saturday from 6 am to 6 pm and made $130 a week. He worked there for four months.

Around this time he finally saw his brother for the first time since they parted ways in Mexico. Arriga had also made it across the border.

Martinez began looking for body work. He asked one man for work and got the usual response — he needed to go back to school. Martinez then explained that he needed to work because his mom died and he had just arrived in the country.

The man inquired when he could start and Martinez said tomorrow. The man asked, “You’re not going to turn me in are you?” to which Martinez replied, “No, I just need money.”

Martinez was now making $200 a week working Monday through Saturday. After two months of working, he moved out of his sister’s house and into his own apartment behind the body shop. His oldest brother then gave him a 1988 Toyota Corolla.

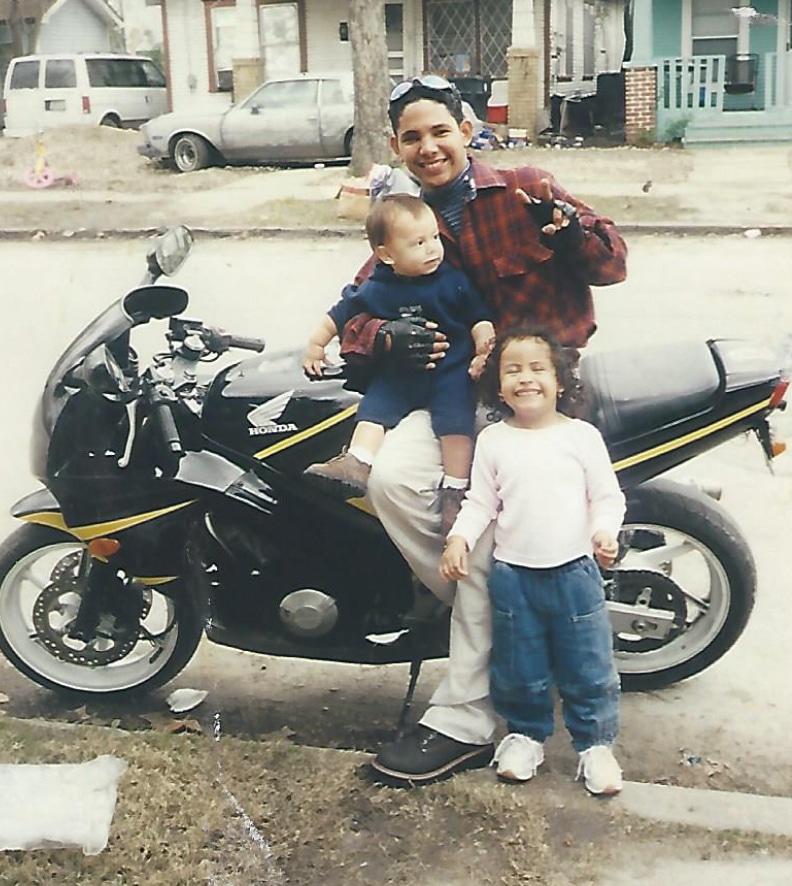

When Martinez was 20, he met Summer Hayden while he was changing the spark plugs on a vehicle. Sparks literally flew, and Hayden became pregnant with the couple’s first child. In 2002, the couple moved to North Carolina. There Hayden gave birth to their first child, Amber, and the couple got married. They stayed in North Carolina for a year and a half.

Hayden and Martinez decided to come back to SWLA to see Hayden’s family and get away from the climate in North Carolina. They stayed with the family for three weeks while Martinez looked for a job. He said nobody would hire him because he didn’t have a resume. Martinez finally went to Shetler Lincoln Mercury in Sept., 2004.

The boss of the body shop, Dennis Primeaux, asked what experience he had, and Martinez responded that he had eight years in body work. Primeaux also asked when he could start. Martinez, once again, said “tomorrow.” He was hired and the dealership sent him to school for a year.

Martinez says Primeaux was the best boss he had ever had. The dealership is also where he met Dannis Begneaux, the painter and shop foreman, with whom he became good friends.

Applying For A Green Card

In 2004, Martinez obtained a lawyer to help him become a legal citizen. His lawyer was the late Shannon Cox of Cox, Cox, Filo, Camel and Wilson.

Cox helped him apply for a green card. In 2006, Martinez’s second child, Hunter, was born. Finally, in 2007, Martinez received a letter from immigration saying his visa was ready, the only catch — he had to go to Honduras to get it.

Martinez and Hayden flew to Honduras. Martinez had to take tests to prove his eligibility to become a permanent resident of the United States. When he walked up to the window to receive his papers, the man working behind the counter ripped up three years of paperwork and said he was being punished for going to the U.S. illegally. He was told, “When you fix your papers, that’s what happens.”

In U.S. law, there are few options for someone who entered the country illegally to obtain a green card. In my opinion, this discourages illegal immigrants from becoming legal. This is probably one of the top reasons some politicians are calling for immigration reform. No one is going to come forward if it means risking everything.

In Martinez’s case, even though he was married to an American citizen, since he came in illegally, the transition to a green card isn’t any easier. The consulate has the power to punish you for entering illegally.

Martinez was told that his wife could go back to America, but he would have to stay. As you can imagine, this created much heartache — to see one’s life go down the drain.

To be continued in the next issue of Lagniappe.

Comments are closed.