What makes vinyl a $1.2 billion industry today? For most who buy vinyl records, it’s that whole sensory rush. There’s the sound, of course, but it’s also the romance — the feel and smell of an LP — that music from a digital source just cannot provide.

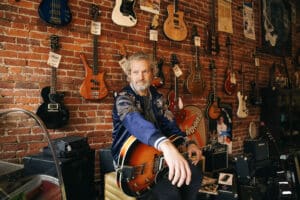

That is what motivates Bam Arceneaux, musician and vintage-visionary, to get up every day and open his storefront at The Emporium on Ryan Street in downtown Lake Charles. All his life, he says, he has understood music differently than a lot of people.

“Put any record on a turntable, and there is a romance that occurs for every living human being on the planet,” he says. “Before you ever fell in love with another human being, I guarantee that you fell in love with a song or a band. The world-at-large became disassociated with the musical romance of life when the digital era began.”

Music has been running through Arceneaux’s veins for as long as he’s been breathing. His grandfather started his downtown Lake Charles music business with a partner in 1946, then went out on his own in 1952.

“Think about it,” says Arceneaux excitedly. “I get chills when I do. Stevie Ray Vaughn played at Scarlett O’s in Lake Charles three times, just like countless other musicians over the years. I would like to think he discovered my grandfather’s shop, Zypien’s Music Center on Iris Street, and bought something, no matter what it was. I am here today because of him.

“I want folks here to understand that unique history — to know just how big a role Lake Charles played in the music industry back then. You’re driving from Florida, say, coming through New Orleans, then through Houston, and maybe going on to Los Angeles. You’ve got to pass through Lake Charles on I-10. Music and recording history happened here.”

His grandfather, Bernard Zypien, joined the army at the onset of WWII and was stationed at Fort Polk in DeRidder. One of 12 children born to Polish immigrants, the young trombonist became the army bases’ band leader.

“He met my grandmother in Shreveport, and they stayed in Louisiana after the war ended, settling in Lake Charles,” Arceneaux says. “I was in Dallas in the early 1990s, where the music scene was exploding. My band was in the middle of everything, sharing stages with some of the top bands of that era: 311, Tripping Daisy, The Toadies, the Nixons, Deep Blue Something, Morphine, Billygoat and countless others. “My grandfather had passed a few years earlier, so I came here to help my grandmother run the family music store, which by that point had become known as an antique store. Once I took the leap to move here, I decided to sink my teeth into the musical history that surrounded me.

“None of the places where that history happened exist today. We once had clubs like Ball’s Auditorium, The Bamboo and Goldband Studio, where Eddie Shuler recorded over 1400 songs over a 40-year span that defined this musical area. All gone now. When they were still demolishing the Goldband studio in 2017, I crawled in to recover as many significant artifacts as possible. I salvaged acoustical tiles out of the studio’s control room fully intact, where all the ‘magic’ happened.

“It was identical to what Sam Phillips had at his Memphis Recording Service in Memphis. His Sun label had Elvis, but Shuler had Phil Philips and his ‘Sea of Love’ hit, which he and George Khoury had to sell to Mercury Records for it to sell 3 million copies and become a top-100 oldie of all time.

“If Eddie had had the reach and resources, think of what he would’ve been able to accomplish. Sun Records and Memphis Recording Service are now a multi-million-dollar musical tourist destination today. We had that, here in Lake Charles! But we let it get away. You can build a new building, but it will never be able to recreate that first one. It won’t have that musty smell. I see my hole-in-the-wall shop as, perhaps, a vital thread that provides a connection to what we’ve lost.”

Arceneaux’s younger customers come out of curiosity, looking for a chance to experience the music of former eras, maybe even compare it to their own. When these two demographics meet in Arceneaux’s space at The Emporium, they’re meeting on a bridge that closes the generation gap.

“I have customers who are coming in to buy the LPs that they once got rid of…because now their kids want to hear Santana, Journey, all that old music from their parents’ yesteryears.

“Think about it. It’s the auto industry that has guided us in how we listen to music. Our car radios went from AM to FM — that was a big thing. Then eight-tracks emerged. Now music is becoming more portable. Then we had cassette tapes and CDs. Today, you can’t buy a vehicle with anything but Bluetooth, which delivers music to us digitally only.

You want to listen to your old CDs in your car? You’d better be willing to pay for that add-on option. It won’t be cheap, either.”

Music is a time capsule, one that preserves the cultural, social, political and emotional facets of all our collective and personal moments in history. You hear Benny Goodman, and you see and feel the big band era’s optimism that took listeners from the Great Depression to the end of a second World War. You hear Elvis, Chuck or Fats, and how can you not be lost in the 50s again? The first few notes of John Lennon’s Imagine tickle your auditory nerves, and you know that the Fab Four emerged as musical ambassadors for the counterculture movement of the 60s.

Art has always ignored boundaries; there are no guardrails that can stop change. Without question, music — the melodies, the lyrics, the performers — reflects that reality. Who could have predicted what the 21st century would bring to humankind? Technology comes flying at us so quickly that it is easy to see why we sometimes yearn to climb into a time capsule. We crave experiences that give us pause to relax, reflect and recover. Arceneaux delivers that, on vinyl, to his customers.

“I recently gifted a friend’s 10-year-old daughter a turntable and a Taylor Swift record for her birthday. I told her mother that it may change her life. That’s not an exaggeration, is it? What song were you listening to when you got your first kiss? Life-changing, wasn’t it?”

Arceneaux is blasting music onto Ryan Street. Today, it’s JD McPherson, who he will be seeing in concert later, in Lafayette. “He’s a guitarist with a voice and style that’s reminiscent of Little Richard. People passing by are drawn into the shop by the music coming out of it.”

Arceneaux realizes that if the powers-that-be can’t see what the past provides, we run the risk of losing the history and the romance of what music can still provide.

“Downtown Lake Charles was a ghost town when I came in the mid-90s,” he says. “For over 40 years, you could walk into my grandfather’s shop though, purchase an LP or 45, and leave with it in a paper bag. You’d get home, unwrap it from its plastic cover, pull that record out of its sleeve, and play it over and over until you wore out the grooves. That’s what we all did.”

Arceneaux says the revitalization of downtown Lake Charles has been an ongoing quest ever since he returned. Despite hurricanes and other setbacks, he still believes it can continue to grow into a place where residents and tourists can shop, dine and remember what made it unique and lively.

“It’s cultural and romantic pulse, alive and well once again,” Arceneaux says. “Just today, I had some Australian tourists come in. I would’ve loved to recommend that they visit an old local recording studio, with its building still intact, housing a retail shop and diner inside, with that smell. We lost that, but folks still want it. None of the places that were part of the SWLA musical roots still exist today. We’ve torn them down, demolished them. I’m just a middle-aged kid, a musician that still plays gigs, but one who wants that history to not be forgotten.”

What is it about the music from our past that fills us with a desire to hear, touch and, yes, even smell it? Was it the simplicity of the melodies, the truth hidden within its lyrics, or the stories behind the performers and their performances? For a visionary like Arceneaux, it’s all of the above, and then some.

“It’s seeing a kid, a teenager, who’s getting a record, or finding a record for the first time,” he says. “There’s that look of wonder on their face. You fold the cover out on your bed. You stare at the pictures as you play the music. You read about the artist. All that went away with the digital age. It became too easy — there’s no contact, no physicality to that whole experience anymore.

“That’s really what this is all about though, isn’t it? When you find music, it gives you an identity. It may even become your identity. It’s your first love when you think about it. I remember that first time for me; I still have my first record player. Double Fantasy by John and Yoko came out about a month before Lennon was killed. I was nine. When my grandfather gave it to me, he explained how much John had meant to everyone who loved his music. I played it non-stop for months.

“Fifty-two years after the Beatles played their last live performance together in England, my Beatles band, Lucy In Disquise, played that same set on a rooftop, on the corner of Broad and Bilbo, right here in Lake Charles. So, when I say it’s going to change a kid’s life, it’s because it probably changed mine.”

Comments are closed.