Southwest Louisiana’s Most Notorious Cold Case

By Brad Goins

It’s often thought that the triumph of the industrial era in Britain was marked by the emergence of a new kind of criminal — Jack the Ripper.

Some think that when his string of murders in London ended in 1888, Jack the Ripper brought his passion for modern murder to the United States. On August 24, 1891, police investigating a report from a New York City hotel discovered the body of a woman who had fallen victim to a monstrous attack. Although the details about the state of the young woman’s body were never released, press coverage conveyed the definite message that the murder had strong similarities to those of Jack.

Police who arrived at the murder scene discovered that the killer had written the words “Okay catch me Boss” in blood on one of the walls of the victim’s hotel room. The message was thought to be a very direct challenge to New York City chief inspector Thomas Byrnes, who, in an ill-advised dig at London police, had told the press that if Jack the Ripper ever made the mistake of coming to the United States, he would be arrested in a few days. (The first Jack the Ripper letter mailed in Britain had been addressed to “The Boss.”)

In the next 11 days, New York city was the site of three more murders of young women, each one marked by extreme violence.

A year and a half after the last of the four unsolved murders, a New York City newspaper received a letter signed Jack the Ripper. It was reported that the letter contained details that only the murderer would have known (although, in 2021, we can hardly prove that was the case).

It was also reported that detectives from Scotland Yard had traveled to the United States, examined the letter and claimed that the handwriting matched that of Jack the Ripper.

No one was ever arrested for the four New York murders.

A Growing Train Town

In Jack the Ripper’s London, there was no more potent symbol of modern industrialization than the train. Trains covered central London with smoke, coal dust and soot. Blocks of housing for low-income residents were razed to make room for the train tracks.

Although it was certainly no London, young Lake Charles was built around train depots.

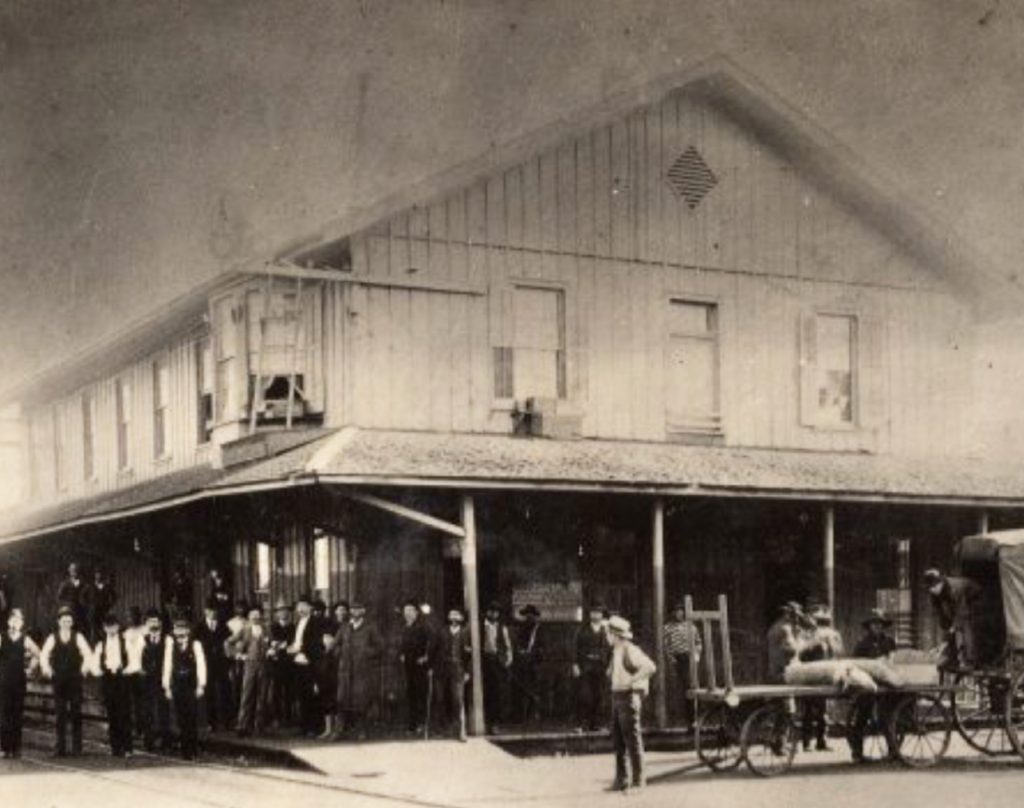

At the beginning of the 20th century, the busiest part of Lake Charles was the area around Railroad Avenue. Known as “uptown” at the time, it was the most robust center of activity in Lake Charles.

Commercial growth in the city moved outward from the railroad depots and spread down Railroad Avenue, which was crammed with saloons, grocery stores, clothing shops, pharmacies, cafes and the occasional brothel.

After dark, uptown Lake Charles could be a scary place. It got wild at night — so much so that it earned the nickname “Battle Row.” In 1903, Lake Charles Police claimed they arrested 102 people for disorderly conduct in a single month on Railroad Avenue.

The ultimate source of this wild activity was the Southern Pacific Railroad Depot, located on Railroad Avenue near Hodges Street. Lake Charles attracted many workers with its burgeoning lumber industry. They arrived regularly on the trains.

In spite of the signs of modern urban growth, Lake Charles still had the culture of the small town. The population in all of Calcasieu Parish was only 9,000. There were no paved streets; streets were covered with shells or gravel. The fire department responded to calls in a single horse-drawn carriage. Residents of downtown Lake Charles tended to know those in their neighborhood by appearance and name.

Many of those who arrived in the formative city rented rooms in the Sunset Hotel, which still stands where it did in 1902 — at the corner of Bilbo and Lawrence Streets. The building originally served as a lodge for employees of the Southern Pacific Rail Railroad and Wells Fargo.

Among those living in the hotel in the spring of 1902 was a woman now remembered only as Mrs. R.J. Kendall. She was the wife of a Southern Pacific Railroad employee whose job frequently took him out of town to Crowley.

On the afternoon of March 14, 1902, R.J. Kendall was working in Crowley as his wife and two daughters stayed behind in Lake Charles to iron out the final details of the family’s rental of a four-room house that was located slightly east, and three blocks south, of the family’s Sunset Hotel room.

Earlier in the day, Mrs. Kendall had taken her 9-year-old daughter Iris and 6-year-old daughter Eunice to the rental home. Then the three walked back to Sunset Hotel, stopping at a grocery on the way to get lunch fixings.

‘I Thought She’d Be Perfectly Safe …’

Back at the hotel, the children repeatedly asked their mother to allow them to go explore their future home on their own. At 2 pm, Mrs. Kendall consented to let Iris venture out. She later told the press, “I thought she’d be perfectly safe since we knew the neighbors and children in the neighborhood played outside all the time.”

As Iris walked to the rental house, she passed saloon owner William Merritt, telling him she was going to see her new home.

After an hour, Mrs. Kendall sent Eunice to find out why her older sister was so slow in returning. Eunice also saw Merritt and informed him she was on her way to see her sister.

Merritt said that 20 minutes later, a distraught Eunice passed him as she went back the way she had come. “My sister is hurt and I’m going after mama,” she said.

Very quickly, mother Kendall came on the scene with her daughter in tow, moving with haste to the rental property on Kaufman. Merritt went with mother and daughter to the house.

He later told the press they found young Iris lying on the floor of a room “surrounded by a pool of blood and with a mass of blood clotted around her mouth.” Whatever they saw must have convinced them the child was dead, as they covered Iris’s body with a white sheet borrowed from a neighbor.

Iris’s throat had been cut so deeply that — it was reported — she was almost decapitated. Local reportage of the time strongly suggested that the disheveled nature of her clothing meant she had probably been sexually assaulted (although this was not specifically stated in the newspaper report).

It was an extraordinarily bloody and barbaric scene, which may have reminded those who saw it of the newspaper stories they’d read about Jack the Ripper.

Not A Single Tangible Clue

The day after the crime, it was reported that LCPD officers “could not lay hands on a single tangible clue” at or near the crime scene. Apparently no murder weapon was found.

A group formed by the sheriff’s office spent the night and the next day questioning people in northeast Lake Charles. A vagrant, as well as a black manager of a store in the area, were arrested, but later released for lack of evidence.

Mrs. Kendall appeared to have been unimpressed by the arrests the police made. “I feel that the murderer is a white man here in Lake Charles,” she told the press. “I think the way it happened was that this man grasped my little Iris by the throat and she recognized him and let him know that she knew him. In his frenzy, he drew his knife across her throat and slaughtered my child as someone would kill a wild beast.”

A railroad employee said he agreed with Mrs. Kendall’s appraisal. “This was not the crime of a tramp,” he said. “The tramps who ride on our railroads would not attempt such a thing in broad daylight where they could easily be seen from the dozen or so houses about a block away, especially not here where the railroad tracks are only 50 yards away and there’s always men a plenty …”

The American Weekly did a good job of summing up the reasons it was difficult to analyze the actions of the elusive murderer. “Four days ago, a little child was murdered in a vacant house, in broad daylight, in a well-settled part of the most populous city of the parish, within hearing distance of a hundred people. The murderer was compelled to enter and depart by the public street entrance …” The criminal was either very bold or very desperate or driven by an unusually strong compulsion — a compulsion that forced him to throw caution to the wind.

Regardless of Mrs. Kendall’s instincts, it is quite possible that the killer of Iris Kendall was a complete stranger who rode into Lake Charles, and rode out of it, on trains. If luck was with him, he could have jumped off a train when it arrived in the city; committed the murder; and been back on an outbound train long before police arrived on the scene. If he’d been accustomed to riding trains, and was familiar with the Lake Charles train schedules, it might have been doable.

Many of the remaining records of the case are sketchy at best. For instance, we have no surviving record of where Iris Kendall was buried. It is thought she might have been buried in the Catholic cemetery at the corner of Iris and Common.

The surviving members of the Kendall family left Lake Charles shortly after the incident.

Adapted from the book Crimes of the Past in South Louisiana by Nola Mae Ross. To purchase books by Ross, call 337-540-6037 or 337-249-0368.

Comments are closed.