PLEASURE CRUISES, STAG PARTIES AND FIDDLE SERENADES

Before Bridges And Cars, Ferries Were A Highly Valued Form Of Transportation In The Lake Area

By Brad Goins

No historical situation better demonstrates the importance of documentation than that of ferries in the Lake Area.

It’s all but certain that at the beginning of the 19th century, there were already several ferries operating in the areas that would eventually be called Lake Charles and Westlake. Proving all that with historical documents is a different matter.

As with many undocumented situations, the origins of the local ferry are shrouded in mystery, myth and fancy. In 1971, the Leesville Leader published a story asserting that it had once been rumored that a Burr Ferry carried passengers across the Sabine River into Texas in 1805. The story went that this ferry was named after the historical figure Aaron Burr, who was said to have crossed into Texas shortly before he was tried for treason in 1807.

What is far more likely is what is well documented: in 1827, a Dr. Timothy Burr operated a Burr Ferry. Burr kept his slaves on the Louisiana side of the Sabine River; his fields were located on the Texas side. Burr might have run a ferry primarily to move his labor back and forth across the river.

Burr Ferry came to an end exactly one century after its first appearance in recorded history in 1827. It ended as almost all ferries did — because someone built a bridge.

In 1892, census reports showed Burr Ferry with a population of 55. When the Leesville paper wrote about it in 1971, that population figure was about the same. Forty years after the end of the ferry, all Burr Ferry had worth noting was three grocery stores, a catfish restaurant and some Civil War ruins.

While the probably mythical stories about Aaron Burr are intriguing, what’s important about the Burr Ferry story is that it documents that a ferry was running in the Lake Area in 1827.

•The Rio Hondo Claim

Common sense leads us to think that in the early 19th century, this area was already a center of commerce because of the number of people who wanted to move goods from the Gulf of Mexico to the inland and vice versa.

Be that as it may, we have no evidence that the settlers of the early 19th century were careful record keepers. Up until the 1880s, documentation about what must have been a widespread ferry business around Lake Charles is scant.

In 1841, some forgotten historian recorded that the Donahue Ferry, which was also called “Spikes River,” served Calcasieu Parish. Another ferry may have operated at the time five miles north of Lake Charles at a spot near a town called Marion, which was later called Old Town.

Other ferries said to have operated in Lake Charles included the Georgia, the Romeo and the Pharr. And such little-known places as Bayou Guy, Burnett Bay, Hecker, Nevils Bluff and Phillips Bluff were likely home to ferries in long-forgotten years.

As tantalizing as these fragments of ferry history may be, it’s most sensible to conclude, as a Weekly American Press writer did in 1935, that there is no record of the earliest ferry that operated in the area.

•Before Hazel

In the years leading up to Lake Charles’ first thoroughly documented ferry — The Hazel — much was happening in water transportation.

The Hartmann’s Ferry, which traveled to a town near present-day Westlake called Bagdad, would eventually be replaced by The Hazel. Although Bagdad has long since disappeared, in the late 19th century, it was home to the thriving enterprises of Grout’s Shingle Mill and Smart’s Lumber Co.

At the same time, the steamboat Evangeline carried passengers from Lake Charles to Westlake. It too would be forced out of business by the popular Hazel.

Other boats would become more obscure than Evangeline. In 1881, the Echo reported that the “steam ferry boat” Nettie had just received a new coat of paint, and as a result, was “looking as neat and prim as a new calico dress.” Nettie was another vessel that plied the Lake Charles to Bagdad trade.

The first powered ferry in the Westlake and Lake Charles area may have been the Ramos, which employed a tugboat powered by steam.

•The Hazel

The 1880s and 1890s saw a sea change in the documenting of Westlake and Lake Charles history. As the area underwent its first population surge, leaders in several fields became active in giving the cities formal organization and documenting the new arrangements.

In 1898, Allen J. Perkins saw to it that the city of Westlake was formally established on a 160-acre tract. Perkins was the right man for the job. An undated map of the period shows that almost the entire southern peninsula of Westlake was owned by Perkins & Miller Lumber Co. (Across the way was an enormous parcel of land owned by “Estate of C. Barbe.”) The map indicates that the population of the area was 10,000, and that it produced 250,000 wooden shingles and 2,500 barrels of rice each day.

Also undated is an old historical photograph showing a large crowd of men and women in Victorian dress clustered around the area where Pujo Street once ended at the shore of Lake Charles. A sign that reads FERRY LANDING is clearly visible.

What was dated was a postcard mailed in 1911 that showed a second sign right next to the one for the ferry; this sign read “STEAMER BOREALIS REX: GULF AND WAY LANDINGS.” The correspondent wrote on the postcard that he was working for Locke Moore Lumber Co. in Westlake, which, he said, was one of 11 lumber mills in the area — mills that included saw mills, planing mills and shingle mills.

A map dated 1898 shows the end of Pujo Street extended by a long planked wharf at which ferries docked. The wharf included a walkway for the general public and an oyster and fish house. An Elks Lodge Hall stood at the entrance of the wharf. Across the street from the Elks was the City Market — the most popular Lake Charles gathering spot of the day. The Pujo Street wharf was a thriving enterprise.

The star player at the once-busy wharf was the ferry called Hazel. Curiously enough, Hazel made her debut in an atmosphere of fear.

A Lake Charles Echo report of 1880 indicated that the public at large believed at first that the Hazel would never make it across the Calcasieu River. It was felt that the ferry’s owner, Cpt. Wehrt, and the main contractor who built it, O.A. Harmonson, had an inadequate knowledge of boat structure, and that as a result, the ferry had been “built by guess.”

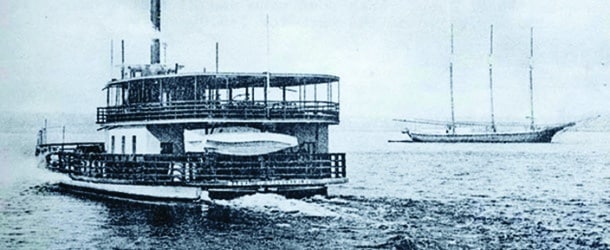

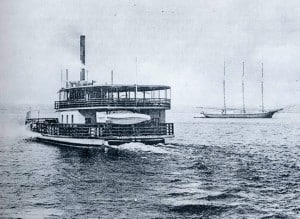

The phenomenal success of the Hazel would prove these rumors to be about as accurate as most rumors. Perhaps at first, Hazel awed the public because it was the largest form of water transportation yet seen on Lake Charles. Contractor Harmonson took two bottoms, which were then “bridged together” to make a platform large enough for 100 passengers. The ferry boat could move these passengers across Lake Charles in 15 minutes.

Another popular contemporary of Hazel was the Perkins Ferry. It’s not clear just when it began; there are some indications that it was operating as early as the second decade of the 19th century. At any rate, we are certain the ferry was acquired by L.M. Dees in the 1890s. (Reese Perkins had established the venture.)

The Perkins Ferry was, reported the Weekly American Press, a “flat-bottomed boat” that was moved by the simple operation of pulling ropes by hand. Each pull of the rope jerked the ferry forward a few feet. If passengers were in a hurry, they grabbed the rope and pulled along. Ropes were simply tied around the trunks of trees on each side of the river.

In its early days, Perkins Ferry charged 10 cents for each worker who rode it. There were charges of 25 cents for each buggy and 50 cents for each wagon. Once the government of Calcasieu Parish took over the operation of ferries, there was no charge for anything.

The construction of bridges made Hazel obsolete in 1916. She would go on to serve as a ferry in Baton Rouge until she retired for good in 1934.

•The West Fork

Documentation about the old West Fork Ferry is detailed, perhaps simply because it operated for so long. Its last day of service was in July, 1968, when the West Fork Indian Bayou Bridge was opened.

The ferry, which The Westlaker reported had “for so many years [been] the only means of crossing the river at West Fork,” carried passengers from Westlake to Moss Bluff.

The ferry was still being written about in 1997, when the American Press’ Allen Seal wrote a detailed history of the craft. Seal related that in the days of the Great Depression, those who wanted to cross the Calcasieu River simply pulled up to the ferry operator’s shed and honked. Pedestrians were given a rowboat and allowed to make their own way to the opposite shore.

It had taken time to build up the West Fork Ferry and its business. At first, development was hindered because the area was inaccessible and what roads came near it were undeveloped.

In its early days, the design of the ferry was remarkably simple. The primary safety feature was a long, heavy “safety chain” that stretched across both ends of the ferry. Some Westlake residents were afraid to be the first to drive onto the ferry because they’d heard the story about the car that had been driven right through the safety chain, with the result that the whole family inside the car had drowned. Whether there was any truth to this story or it was sheer urban myth I don’t know.

The West Fork Ferry lasted long enough to go through the full evolution of ferries. It started as a craft moved by two workers who used a “pull handle” that was attached to two ropes. The ferry was supposed to be able to carry four cars, but the parish engineer of the time, Rodney Vincent, recommended that it carry only two. He also suggested that drivers opt for the Perkins Ferry, which he described as “modern and motorized.”

The West Fork Ferry was eventually equipped with a four-cylinder Ford engine. In the 1950s, the ferry progressed to two six-cylinder engines and the ropes were replaced by 3/4-inch steel cables.

The documentation of the West Fork Ferry gives us some of the most charming instances of ferry lore. When the four-cylinder engine created an imbalance on the ferry, the owners compensated by putting a large box on the ferry and filling it with dirt. Workers used the dirt to grow greens, onions, radishes and other vegetables. Riders referred to the spot as “The Garden.”

Also of interest was the curiosity of the Westlake people about what this large craft would do when it was struck by the Great Flood of 1953. Those who stuck around to view the effects of the flood waters may or may not have been surprised to see the West Fork ferry boat floating serenely in the spot where it had been securely tied to the tops of cypress trees.

The ferry would witness the evolution of Westlake traffic. There was a time when Westlake drivers waited up to an hour before six cars came to the ferry. But by 1968, the growing “industrial complexes” of Westlake had created so much traffic that they had rendered the ferry obsolete.

•Challenges Of Ferries

Even in the early days, running a ferry was more than a matter of merely pulling a rope. Ferrymen were obliged to be acutely aware of water levels and to adjust ramps and cables in response to them. The changing of cables at the end of one trip and beginning of another was a difficult operation.

As ferries in the Calcasieu Parish area gradually moved from private to government control, they began to create challenges for government. In a 1956 article (“The Vanishing Ferry”) the American Press reported that the maintenance and operation of area ferries accounted for the single biggest expense to local government — $60,000 a year.

At the time, parish government paid for the Perkins and Indian Bayou ferries, the Dunne Ferry (on the west fork of the Calcasieu River), the Anthony Ferry (on the Houston River), the Gum Cove Ferry (on the Intracoastal Canal), as well as ferries at Gibbston, Black Bayou and Creole. The ferries ran 24 hours a day.

The Press quoted assistant parish engineer Arthur Darnstead as saying that the ferries were his “biggest headache.” One of his big challenges was making sure the ferries met safety regulations. He told the Press that shortly before his interview, he’d worked six straight hours to fix a “bull wheel” on the Indian Bayou Ferry. He said that when he was finished, his clothing was so dirty he had to throw it away.

Slow-moving as they were, in the 1950s, ferries were central to the area’s Civil Defense effort. All evacuation plans took into account the schedules and capacities of ferries, which were considered viable forms of evacuation.

•Why Ferries Matter

In 1935, E.D. Stagg wrote for the Weekly American Press, “the present bridge across Calcasieu River at Lake Charles is much more efficient than the old ferries … but it certainly isn’t nearly as much fun.”

What was so fun about them? Stagg probably idealized the issue a good bit when he wrote, “one can imagine now the romance of travelling down a moonlit river dancing to the strains of a fiddle and accordion.”

We know that in their day, ferries did what cruise ships did — they carried large crowds to the events they found enjoyable. Certainly there were plenty of business reasons to take the ferry to Bagdad back in the day. But we’re told that, at one time, Bagdad was considered an ideal location for picnics. That fact no doubt accounted for many fond memories of ferry rides.

We also know that many valued the Hazel as a craft that took them to the diversions they found most satisfying. The ferry was often charted (at a high rate) to take a group for a night ride to Prien Lake or Big Lake. It was sometimes rented by groups of men for “stag parties,” which appear to have been largely fishing parties.

Sadly, the lore of local ferries largely preceded the orderly documentation of local history. At any rate, ferries vanished quickly as large bridges and widespread car ownership fundamentally altered the nature of travel across bodies of water.

In the same story in which E.D. Stagg praised the “fun” of ferries, he noted that the majestic old riverboat Rex no longer carried passengers. It had been tied to the wharf at Pujo Street, which had once been the most popular local gathering place in Lake Charles. Said Stagg, the old Rex was becoming “rather dilapidated.” But he remembered a time when it had carried local pleasure seekers all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

Comments are closed.