In Many Cases, Southwest Louisiana’s Post-Rita Recovery Coincided With Dramatic Improvement

By Brad Goins

Hurricane Rita was such an oversized storm that it’s a challenge to the imagination to conceive of the force it brought to bear on Louisiana.

Rita was the strongest tropical storm that has developed since storm statistics have been kept.

When it made landfall as Hurricane Rita on Sept. 24, it was stronger than Katrina — a Category 5 hurricane that was the fourth most intense ever recorded. (Katrina weighs in at No. 6. It’s not without reason that people call 2005 the worst storm season in U.S. history.)

Although few will remember it now, Gov. Kathleen Blanco had already declared Southwest Louisiana to be in a state of emergency before Rita hit. For one thing, Lake Charles was faced with the prospect of dealing with thousands of refugees from Hurricane Katrina, many of whom were encamped in the Lake Charles Civic Center, whose grounds had been surrounded by fencing to control access to the grounds.

Having just seen the havoc and destruction in New Orleans, local leaders in Southwest Louisiana knew “they had one chance to get it right,” writes Richard Cooper, once a senior fellow in homeland security at George Washington University.

With the natural inclination to focus on the successful recovery effort, it’s easy to overlook the massive clean-up effort that proceeded all reconstruction efforts. Before the concrete could be poured and the sheetrock hung, the Army Corps of Engineers removed household debris from 2,000 battered Lake Charles houses. The Coast Guard had to haul away 57 Lake Area boats that had been disabled by the storm.

The federal government provided $140 million for 1,800 different debris removal and emergency service projects in Southwest Louisiana.

FEMA provided $400 million in housing assistance, and also allotted $60 million for debris removal in Calcasieu Parish alone. The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) provided Lake Charles a payout of $525 million. (The percentage of Lake Charles residents who are eligible for NFIP policies and obtain them is well above the national average for those living in flood-prone areas.)

In the weeks following the storm, it was necessary to install temporary housing for 16,000 local residents.

After Rita, the Small Business Assoc. approved $50 million in loans for 700 reconstruction projects in Southwest Louisiana. The amount provided for personal residences was even greater — $76 million for 1,600 projects.

This was just some of the groundwork that had to be laid. Always and everywhere, the bulk of the groundwork was debris removal.

Monuments Of Recovery

Once the hurdles of debris removal and service restoration were cleared, some eager entrepreneurs and bold visionaries focused on single reconstruction plans that would create master-works of construction greater than the ones they had replaced. It was a phenomenon Cooper called “the Rita Renaissance.”

One of the recovery projects that required the heaviest investment of capital was that of the restoration of the Chennault Airport Authority in Lake Charles. Hanger B and Annex B were completely destroyed by Rita. The rebuilding involved both repairs and code upgrades for more than 250,000 square feet of building spaces. In less than three years, all the work had been completed.

Less costly but still capital-intensive was the re-creation of the Lake Charles Regional Airport Terminal. The entire terminal was flooded by Rita. In addition, it suffered such extensive damage from storm winds that it was structurally compromised.

This was an instance in which the reconstruction opportunity was used for growth and improvement. The new terminal was 44,328 square feet — an almost 50 percent increase in size over the old building. It would take exactly seven years to complete the immense project.

The Burton Arena is part of the Burton Complex. The Arena was completely destroyed by Rita. It would take until mid-2012 to complete the reconstruction of the 54,000-square-feet structure.

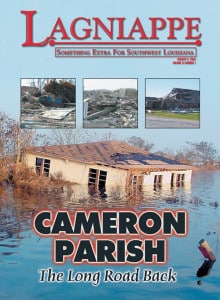

Cameron Monuments Of Recovery

There were equally high-dollar success stories in Cameron Parish, where the storm damage was much more devastating than in Calcasieu Parish.

It took six years, but the South Cameron High School and Elementary School was rebuilt. (After Rita, all that had been left standing in a large portion of the school was the basketball goals in the gym. In a surreal scene, they were the sole objects rising among a vast expanse of debris.)

In this project, too, there was an upgrade to a larger size, with the original 95,000-square-foot building being replaced with a 101,000-square-foot school.

During the process of rebuilding, temporary facilities and texts, along with food, were provided.

(In addition to the school, a new impressive-looking school board headquarters was eventually constructed.)

The Cameron Parish School Board Administration building

Just like the schoolhouse, the South Cameron Memorial Hospital experienced severe flooding and was structurally compromised by winds. Again, there was an effort to use rebuilding as a chance to bring the community something bigger, newer and more efficient. The 26,000 square feet of the old hospital was increased to 31,000 feet. In addition, the new structure was elevated above flood plain levels. FEMA contributed more than $26 million to the effort.

The Rockefeller Wildlife Refugee lost 1.5 million cubic tons of soil during Rita. The refugee’s levees were comprised. Material dredged from an adjacent canal was used to bring levees up to their earlier level. The effort cost well in excess of $10 million.

‘Everybody Wanted The Community To Come Back’

These success stories were made possible by the rebuilding of the very foundations of the Cameron community. This rebuilding had to start from scratch. Only two houses in Cameron were not destroyed by the storm.

Within the first few months following Rita’s landfall, a few hearty souls were conducting business out of buildings that no longer had roofs or walls.

At first, Cameron recovery efforts were minimal and moved in fits and starts. The owner of the badly damaged city hotel spent his hours putting up new studs in his old place of business.

For months, debris removal was the biggest and most lucrative business venture in Cameron Parish. Looming dumps of debris could be seen around the parish, some stretching out 100 feet or more.

Most of the population of downtown Cameron at this time was made up of employees of the U.S. government, many working for FEMA.

Members of the Army Corps of Engineers had made a bunkhouse of the judge’s quarters in the Cameron Courthouse — the one major building in the city that survived the storm. Cameron Judge Hadley Ward Fontenot, who would eventually be appointed to the Louisiana Recovery Authority, remembers walking into his office and seeing Corpsmen’s “underwear and socks” hanging up and “drying.”

But Fontenot started his recovery work with bigger problems than drying socks in his former office. For three to four weeks after Rita’s landfall, he could not find his secretary. And he had virtually no network he could use to find her.

“We were totally out of communication [in Cameron]. The sheriff’s band was out. You can’t imagine how we felt” about being unable to communicate with anyone.

But nothing in the recovery process was easy. Fontenot’s clerk of court could only find adequate office space in Jennings. This meant that court papers had to be continually shuttled back and forth between Jennings and Lake Charles.

After a few months, Fontenot decided enough was enough. “We decided it was time to make a move.”

Following his return to the Cameron Courthouse, Fontenot had to determine that he could indeed build a judicial system in a storm-ravaged land with very little remaining population.

The “first thing” he felt he had to do was “test the jury system.” An immediate challenge was to figure out how to deliver the 100 jury summons — many of which were eventually delivered by hand.

“We had a remarkable response,” says Fontenot. “We got about 85 percent.” (The usual jury summons response rate in Cameron is 50 percent.)

Given the degree of damage to coastal Cameron Parish, it’s no surprise that for a time “there was a drive on to move the functions of the county seat to the northern part of the parish. But the [Cameron] courthouse could not be moved … The maintenance of the court system kept it grounded.”

Fontenot had long believed that the courthouse was the heart of Cameron and the judicial system was the essence of Cameron culture. The direction Rita recovery has taken has borne out his beliefs.

In today’s Cameron, he says, a complex of impressive buildings rises up around the courthouse. Among these are the new District Attorney’s Office, Police Jury Office and jail. (Before the storm, the jail was located inside the courthouse — a system that had been inadequate for some time.)

Other Recovery Successes

In addition to the establishment of a strong judicial system and the cluster of new buildings that contribute to it, Fontenot sees other remarkable successes in Cameron’s Rita recovery. One of these is the sustaining of the Lions Club.

The club, which had been around since the 1940s, was unusually active for such a small town. After Rita, Fontenot and others “worked on having it come back as a commuting club.”

Another recovery success is the reinstituting of the Cameron Fishing Rodeo. Of course, the near-complete destruction of the Cameron Jetty almost destroyed the rodeo as well. The post-Rita event “started very moderately” at locations outside of Cameron, says Fontenot.

But with the eventual repair of the Jetty, the Cameron Fishing Rodeo returned as something very close to its original incarnation. (Fontenot notes that this event is quite different from the Calcasieu Fishing Rodeo. The Cameron affair focuses on fishing in “brackish water,” such as that of Big Lake or bayous. Redfish and speckled trout are among the most common catches.)

‘Just Hand Us A Piece Of Plywood’

Eight weeks after Rita hit, says Cooper, Lake Charles Mayor Randy Roach told a Back to Business Conference, “just hand us a piece of plywood, and we’ll take it from here.”

This was a succinct prophecy of the huge construction enterprise and mindset that would become a mainstay of Southwest Louisiana culture. Not only would the vast number of building and repair projects push the local economy to record levels, but these levels would stay solid until Hurricane Ike hit the area, bringing with it another boom in construction and sales of building materials.

Southwest Louisiana gained a reputation as a place where construction was ongoing and jobs were available.

Although many groused about the new tougher building codes that required residences to be elevated to the degree that they could survive storm surges, the positive result was that long stretches of newly constructed residential structures contain some of the most storm-resistant houses in the country. Many improved on the code requirements by finding or developing new hardware that would solidly anchor roofs to the buildings beneath them.

Whether it was mainly because of Rita, or a combination of Rita and other factors — such as Hurricane Ike, the BP spill and the cluster of major business agreements that would lead to what would eventually be called “the boom” — Southwest Louisiana built an economy strong and resilient enough to attract the nation’s interest time and again. When the Great Recession was hammering most of the United States in 2010, SWLA’s Lakeside Bank was the only bank in the U.S. to be chartered in the entire year.

George Swift recalls a phone call from a New York Times reporter who seemed skeptical about SWLA’s stability. Not only was she taken aback by the chartering of the bank, she had had a hard time understanding why Lake Charles’ unemployment rate was so much lower than that of the rest of the country.

“Rita brought us together as a region like never before,” Swift later told Cooper.

Patrick Moore, who was integral in planning the new lakefront development, told Cooper that Southwest Louisiana enjoys a “regionalism … that exists in ways like no other in Louisiana.

“From the beginning of this state, we’ve clawed our way to survival. We’ve been beat up, burned down and blown away in I don’t know how many ways, but we know how to work together … that … is the definition of resilience … The opportunity to build something stronger that can carry us into the future has been seized like never before.”

Moore said he did his post-Rita planning and construction from a desire to “fix, improve, give hope and spur economic development.”

Long-term Recovery

Moore told Lagniappe that as he moved into his work on the post-Rita recovery of the lakefront and downtown Lake Charles area, he was heavily influenced by a book that appeared at the time: The Resilient City: How Modern Cities Recover From Disaster by Lawrence J. Vale.

Thus, even resilient cities recover over the long-term in a very gradual way. Moore applies the model to Cameron; he told Lagniappe, “It’s taken a while for anything meaningful to happen.” But on the other hand, after 10 years, Cameron, Moore says, “is actually the center of energy — almost for the world.

“Nothing good is easy,” says Moore. “Nothing really substantial is quick.”

He cites as an instance a stage of lakefront development that was reached some time after Rita’s landfall. When one member of the Louisiana Recovery Authority saw it, she commented, “This is the first real project that’s coming out of the ground in Louisiana.”

And Moore is quick to point out that monuments of recovery aren’t limited to large, impressive structures built of bright red bricks and gleaming glass and metal. He thinks solid recovery requires three basic facets:

1. Projects

2. Policy

3. Programs.

“You’ve got to get in there and think through this stuff,” says Moore.

He figures that, ultimately, it’s more important for cities struck by disaster to have resilience than to have sustainability. Sustainability is, he says, the ability to “stay in position.” In contrast, with resilience, “we know we’re going to get our ass kicked. [Resilience is] our ability to bounce back and be better.”

Sources:

“Calcasieu Parish — Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: A decade of progress through partnerships,” Federal Emergency Management Agency Report.

Cooper, Richard. “The Rita Renaissance,” in The Year in Homeland Security, 2010 edition.

Laborde, Errol. “And Then Came Rita.” Louisiana Life, July 2015.

“USA: By the numbers. FEMA recovery update for Hurricanes Katrina & Rita. April 7, 2006,” Federal Emergency Management Agency Report.

Comments are closed.