In The Brave New World Of School Nutrition, There’s No Place For Buttery Rolls Or Chili Dogs

By Brad Goins

If you’re a grandparent with grandchildren in the Calcasieu Parish School system; and you and your grandchildren compare notes about school lunches; then you know things have changed.

Back in the day, says Calcasieu Parish School Food Services field manager Brenda Wright, “everybody liked [the school] rolls … Bread was always [hand-made] at the site. The talk of the town was the school rolls.”

But in the last few years, Calcasieu Parish schools have been obliged to serve whole wheat rolls, which some students refer to as “hockey pucks.”

This year, the parish will try to use a USDA flour mix that is 51 percent whole wheat, but that looks white. Says Wright, “I can’t wait for them to say, ‘Oh, we got our rolls back.’”

In years past, students in high school could queue up every day for a special line that served hamburgers, French fries and chili dogs. Not any more.

These days, French fries can be served once a week at the most. And they can’t be served at all if the school is serving corn in the same week. That would be serving two starch vegetables in a week — a big USDA no no in 2015.

What Happened?

So what happened? Some may think that school menus follow political or dietary trends — perhaps in a rather haphazard manner.

In fact, the make-up of lunches in the U.S. educational system is largely the result of U.S. military history.

When the U.S. National School Lunch Program was created in 1945, it was designed specifically to address a problem of the military. Too many American recruits were showing up in a state of malnutrition. It was thought that school meals of a certain type might go a long way towards solving this problem.

In the new millennium, the military situation has taken an about face. As the U.S. moved into the 2010s, military leaders informed us that recruits were now showing up in a state of obesity. Two consecutive U.S. government studies on the matter were titled Too Fat To Fight.

Once again, the USDA changed the make-up of the school lunch. And the change was a big one.

The new standards are, says Patricia Hosemann, director of Food Services, “very restrictive” when it comes to the number of calories and amount of sodium in the student meal.

School cooks no longer add salt to any school foods. Salt shakers no longer sit on school tables. You’ll also see no bottles of Tobasco. (Tobasco is high in sodium.) Today’s school cooks are obliged to learn how to work with healthy but unfamiliar spices — cumin, garlic.

Perhaps most dramatically, the desserts we old folks grew up with — pudding, pie, cobbler — are no longer served at school. In fact, regular desserts aren’t served at all in Calcasieu Parish School meals. High school students get a serving of cookies … every three weeks.

And while there’s plenty of fresh fruit, there’s no longer any fruit juice. It’s too high-calorie.

Hosemann admits the current USDA standards “are tough” to meet. She says it can now take as much as two weeks of solid work to prepare the plans for just three weeks of meals. The standards constitute a “drastic change” from the past, says Calcasieu field director Kathy Breaux.

It ‘Doesn’t Taste Right’

Readers are probably already anticipating students’ complaints. Many students say the low-salt, low-sugar diet “doesn’t taste right.” It’s easy to imagine that students raised on a steady diet of Hot Pockets and Taco Bell could be intimidated by a school lunch made up of six tablespoons of yogurt, a fruit cup, half a cup of enriched macaroni with fortified protein, a whole wheat roll, 3/4 of a cup of carrots and a cup of milk.

In 2015, a high school lunch cannot contain a single gram of trans fat. Saturated fat must make up less than 10 percent of total calories. Milk must be chocolate skim or 1 percent white.

Staff does what it can to alleviate student displeasure with the meals. Today’s students, who are accustomed to white rice, can eat only brown rice in school. When brown rice is served, says Hosemann, “we hide it.” Brown rice is covered with gumbo or red beans, which are acceptable to students.

As for the once-a-week serving of beans as a side that’s permitted by the USDA, Hosemann does her best. During the first year of the new standards, she served garbanzo beans, as she liked them herself. “Public opinion crucified me,” she says. (She says in the first year the new lunches were served, the superintendent received hundreds of emails from disgruntled parents about the quality of the meals — each of which was made in strict accordance with USDA guidelines.)

With garbanzos out of the picture, Hosemann went ahead with black beans, thinking that youths might be accustomed to them from meals at Mexican restaurants. But students weren’t interested.

This year, Hosemann will try black-eyed peas and hope for the best.

Hosemann tried to make school meals more amenable by introducing wraps — a measure that met with only limited success. She’s trying to think of a way to work smoothies into the mix.

She’d like to work in fast food-type options — such as, hotdogs, say. But the manufacturers of such foods have thus far been very resistant to making products that conform to the new USDA standards.

“I am open to any ideas on how to increase participation,” says Hosemann.

Calcasieu Parish students aren’t the only ones complaining. The USDA reports that since the new meal plans went into place, student purchases of school meals have dropped 16 percent. “[In addition to Louisiana], the rest of the nation is struggling,” says Hosemann. In Louisiana and elsewhere, many districts see as little as 10 percent of students buying school meals.

Eating Problems In The Home

What some students choose as alternatives to school meals provides a clear picture of the questionable contemporary eating habits that school staff are struggling with. These days, many students in Calcasieu Parish bring sack lunches that parents have filled with a bottle of pop and a large bag of Doritoes. Some Calcasieu parents bring their children bags of Taco Bell and Wendy’s during the lunch hour.

While school officials have discussed ways to fight such behaviors, as far as anyone can tell, a parent who brings a student a bag of hamburgers at lunch time isn’t breaking any rules.

As these trends indicate, many students are coming to school with a history of unhealthy eating habits at home. Many students now live on a steady diet of fast food or prepackaged food heated in microwaves. This high-fat, high-sodium diet limits students’ tastes, and can, if taken far enough, make them susceptible to obesity.

Clearly, many students are not eating as their grandparents did, with a breakfast and dinner prepared from scratch every day. “These kids have no experience of meatloaf,” says Hosemann.

Many contemporary parents may have little or no experience with serving their children something other than pizza, a Family Pack from Popeye’s or prepackaged microwave items. “We need a lot of parent education,” says Hosemann.

And it’s not just home eating that’s the problem, say food service staff. The U.S. society of 2015, they say, is one that places a very high value on food.

“Food is a reward,” says Breaux. Youths who reach a milestone or accomplish something special are often rewarded with pizza parties or trips to retail chain restaurants. Many school or church fundraisers revolve around food — often candy or desserts.

“I think that’s a drawback,” says Breaux. “Kids see it in that light. That’ll be hard to change.”

The Obesity Issue

With the present-day U.S. food culture being what it is, it’s little surprise that many youths struggle with obesity. What may shock some Lagniappe readers is that students as young as 3 are entering Calcasieu Parish Schools after they have already been given a diagnosis of obesity.

Last year, six 3-year-olds who had been diagnosed as obese were admitted to parish schools. Of these six, two already had high blood pressure.

When doctors give obese students special diets, parish schools are obliged to serve the students meals that conform with the diets. Hosemann says the schools get “unreal” dietary requirements for obese students.

In the 2015 school year, the parish was obliged to follow special diets for 333 students. Most of these diets were for students who’d been diagnosed with diabetes or were lactose intolerant. But schools must also accommodate students with an array of food allergies.

Enthusiasm In Spite Of It All

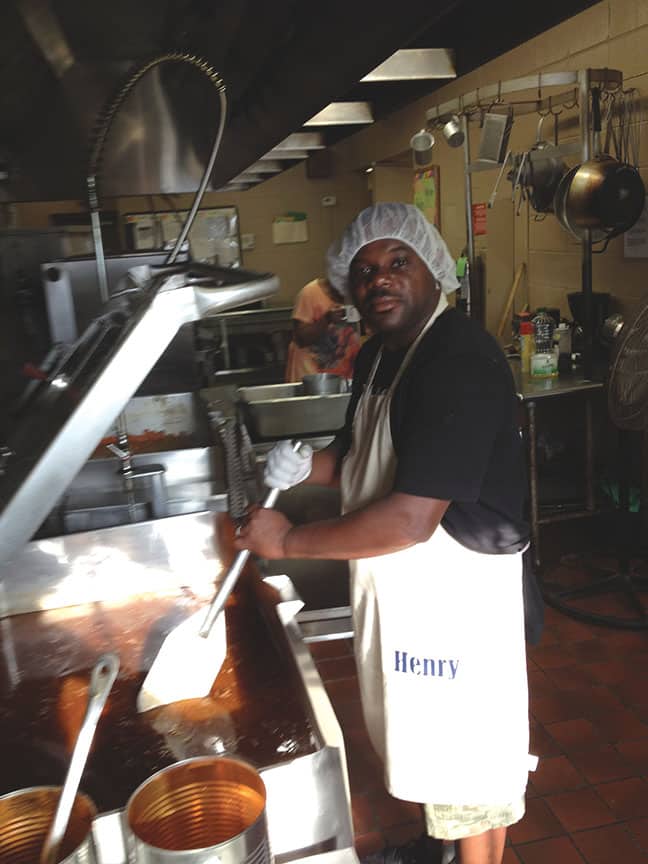

Brenda Wright, field manager for Calcasieu Parish Food Services, and Lucille Conway, manager of City of Lake Charles Summer Feeding Program.

The administrators I talked with weren’t happy with the speed with which the latest set of dietary guidelines were put in place. “They’re trying to catch up on 20-30 years in one fell swoop,” says Hosemann.

But interestingly enough, they all support the principles behind the new requirements. They like the idea of young people eating healthy food at school.

They feel that the “younger ones” — students in the early years of elementary school — are indeed learning good eating habits from their school meals. “We’re doing good,” says Wright.

Concern is particularly acute for students who come from homes where they don’t get enough to eat. “We see kids coming in here on Monday morning and they’re starving to death,” says Hosemann.

For students who are more than happy to eat school food, Calcasieu Parish offers options in addition to regular meals. There is the Best USDA Program, which provides students with a serving of fruit or vegetables as a mid-afternoon pick-me-up. There’s also the After-School Snack for those involved in after-school activities. This program gives students cheese crackers and milk. Food for these special programs is provided free for students who qualify.

For students who want to eat the regular school lunch, prices are $1.35 for the middle school meal and $1.50 for the high school meal. These prices haven’t been raised in 10 years. Since 1991, the parish has also served breakfast to students.

Hosemann feels that food requirements in schools will get tougher before they get more lax. She thinks it’s likely that schools will soon be required to purchase food with no additives. Of course, this would mean a huge increase in costs.

It’s something parish staff are used to; when it comes to food, “the healthier it is, the more costly it is,” says Hosemann. Fortunately, food costs are covered by a fixed fund. But, of course, record-keeping is meticulous — and all the more so as costs rise.

As daunting as all the new challenges are, Calcasieu food service administrators are quite excited by the prospect of giving children healthy food (and perhaps even guiding them towards healthy eating habits).

“I’m trying to put the puzzle together … You’ve got to be a little creative,” says Hosemann. But the news — overall — has been good so far. “We’re making it, unlike many school districts,” she says. And Wright thinks there’s more success to come. “I think it’s going to be a winner.”

Comments are closed.