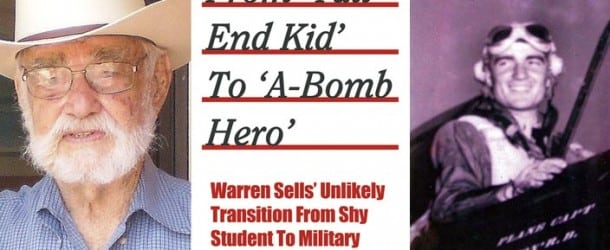

In his 90th year, Warren Sells, who grew up in Cameron Parish and Lake Charles, has a lot to look back on.

This veteran of three wars characterizes himself as an extreme introvert. But in his military career, he was an ace Navy pilot and commanded men who still respect him today. He photographed a hydrogen bomb explosion and was translator for a meeting between Khrushchev and Queen Elizabeth. He turned down a chance to be an astronaut.

“I started a war,” he said. Yes, Sells was the lead pilot of the very first U.S. air raid on North Vietnam.

Sadly, his distinguished career ended when an attack by antiwar demonstrators led him to resign from the Navy, leaving him bitter.

Sells was born at Burrwood, in Plaquemine Parish, in 1923, when his dad John was a boat captain. When Warren was old enough, John got him a job on a dredge boat that created the Calcasieu Ship Channel, which allowed ocean-going vessels to sail up the river to the Port of Lake Charles.

Sells graduated from Lake Charles High School and went to John McNeese Junior College when it opened in 1939. He credits the rigor of classes at LCHS with his success in college. “Aunt Ruby” Sells taught at LaGrange High School, and his grandmother taught in Cameron, so he was no stranger to education.

“There were only a couple hundred in my graduating class at McNeese, and only about 400 students in all,” he said. While at the school, he received the Luidal Howard Butler award for math. “I was smart, and I was good at math,” he said in a recent interview at his home in Kerrville, Texas. He received a two-year degree from McNeese.

When World War II broke out in 1941, he said, “I didn’t want to go to war, and you didn’t have to go in the draft if you were in college, so I got a math scholarship and went to Texas A&M.”

His dad was an advocate of education, but Sells paid his own way in college. He worked his way through his junior year by waiting tables and working on a boat back home. “But I couldn’t afford to continue, so I came back to Lake Charles,” he said.

That made him eligible for the draft, and he got his orders to report to Lafayette for induction. A streak of impatience got him into the Army Air Corps.

“There was a long line of naked young men who had said ‘ah’ and bent over to be checked by the doctor. I was colder than hell. I noticed there was a shorter line, with only about 10 guys, so I asked someone what that line was for. He said that was for aviators and all that was required were good eyes and a stout heart.

“The doctor had already determined that I had good eyes and a stout heart, so I switched lines to become an aviator. Since I had more than two years in college, I was allowed to join the Navy,” he said.

“They sent me to Minnesota for aviation training. I had never touched a plane before. I had never seen snow before either. I was looking at the Stearman biplanes on the base. They were on skis, instead of wheels, for landing in the snow.

“A flight instructor came over and told me to get in the second open cockpit for a flight. I just had on khaki pants and the little jacket they had given us to keep warm.

“There was no runway; planes just landed and took off in an open field. [The flight instructor] gave me the gosport speaking tube with cups over my ears and a funnel for him to speak to me. We took off and he told me to take the stick and the throttle. We flew around for about an hour, and when we got back to the field, he told me to land the plane.

“When we got back on the ground he said, ‘You’re an aviator.’ I told him, no, that was my first time in a plane. ‘Mr. Sells, you are a born pilot,’ he said.”

“It was the first time in my life I was congratulated for anything,” he said wistfully.

The shy high school and college student and Navy pilot had never dated. However, back at McNeese, he caught the eye of a very determined young lady.

“From the first time I got to McNeese, ‘this thing’ started chasing me. She was very aggressive.”

“This thing” was Theresa Isaac. Her father John was a successful real estate investor in Lake Charles.

Finally Warren relented, and the two were married. The life of a Navy wife is very difficult, Sells said, so he told her he would leave the service so she wouldn’t have to endure his long absences.

“She said absolutely not. She loved the Navy, and she said if I left it, she would leave me.”

The Navy’s first jet was a Ryan FR-1 Hellcat. It had an internal combustion prop engine in front and jet engine in the tail. Sells was assigned to an FR-1 squadron aboard the carrier USS Ranger.

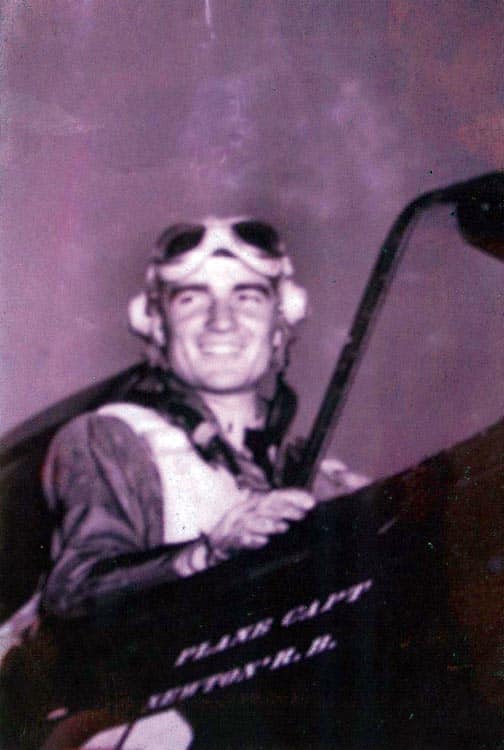

Even in the Navy, “I was an extreme introvert; very shy. In flight training, I was the ‘tail-end kid,’ hanging back behind the others. We flew the Grumman F6 Hellcat fighter planes the Navy used for carrier-based aviation. I went to the Pacific not long before the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending the war.

“Everybody was going home. I had applied and the Navy approved me to stay in. Those who were continuing in the service were dropped off at Pearl Harbor.

“One day, an officer asked if we wanted to go to Bikini [Atoll] to photograph the fleet during atomic bomb tests. We went off a little carrier, and three of us flew ahead of the B-29 bomber that carried the [thermonuclear] bomb.”

The fighters peeled off just before the bomber reached the target area, “and we headed away at top speed.

“They had us all covered up, and we wore welder’s goggles. When that thing went off, I heard a big ‘ping’ as the shock wave hit the plane. The engine died. We could see that cloud 40,000 to 50,000 feet in the air.

“It was instantaneous, the flash, the shock wave, that cloud.”

After a bit, he was able to restart his engine.

“On my new assignment, I went from a nothing, tail-end kid to an A-bomb hero. Other men looked up to us. I could do just about anything I wanted, and when they asked me what I wanted, I told them I wanted to be in an FR-1 squadron.”

The Navy’s first jet was a Ryan FR-1 Hellcat. It had an internal combustion prop engine in front and jet engine in the tail. Sells was assigned to an FR-1 squadron aboard the carrier USS Ranger.

When the real jets came along, he was among the first jet pilots to land on a carrier. “I was becoming a good carrier pilot,” he said.

He was sent to the Patuxent Naval Air Station in Maryland as a test pilot to fly new airplanes. “I flew alongside Gus Grissom, Sam Shepherd and other test pilots who became astronauts,” he said.

“Then the war was on in Korea. I was a night fighter pilot, or as it was called, an all-weather pilot. Today all carrier fighter operations are at night, but I was among the first who flew off the ship at night. Of about 100 pilots on that carrier, only about six of us could land at night. It was rough, with just three flashlights to guide us in.

“Our mission was interdiction: taking out trains and truck convoys to disrupt the enemy’s supply chain.

“The captain called in me and Sam Shepherd, who was in my squadron, and said, ‘You’re going to be astronauts or you’re going to be in the Blue Angels.’

“I was in an A4 Skyhawk squadron. I was a Navy Top Gun with 126 missions. Pretty good for the ‘tail-end kid from the swamps of Louisiana who was always at the back of the line.”

When they left the office, “Sam kept jumping up and down with excitement, but I held back and asked if I could think it over. I went back and told him I didn’t want to be an astronaut, I wanted to be a squadron commander. Sam went his way and I went mine.”

Sells went to Sandia Base in Arizona. It was all very high security.

“We were all sitting in a room, and in front of us was this 15-foot thing. We learned it was a hydrogen bomb. They told us we were going to be flying with them. I was going to be an A-bomb pilot. The official designation was special weapons pilot.

“We had very intensive training. We learned to take that thing completely apart and put it back together and to attach it to the plane.”

On board the carrier, the plane was surrounded by a curtain as the weapon was loaded. “My mission was Vladivostok, Russia. We knew it would be a one-way trip, because if we dropped that thing, it would take us out in the blast,” he said.

“Just in case I was shot down and survived, I went to the Navy Russian Language School. I was smart and always did well in school and at college, but this was the hardest thing I had ever done.

“My plan was that if I got shot down, I would find some peasant clothes and keep my head covered. I would take a cart to act like a peasant and escape to the border.”

His admiral was in a party that was to meet Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. “He told me I would be his translator. I was sweating blood. The next morning, Khrushchev said he wanted me to come as his translator when he met Queen Elizabeth. That little bastard could speak English, but I was one of about five interpreters around him.”

Sells said Khrushchev was widely misquoted in his famous speech at the United Nations. The accepted translation was, “I will bury you [United States].” But, said Sells, “that was a misinterpretation of what he actually said. It should have been translated, ‘I will outlast you.’”

The notoriety the misquote received ruined Khrushchev’s career, Sells said.

After Viet Cong troops conducted damaging strikes against U.S. installations in South Vietnam, “On Feb. 7, 1965, President Johnson called the (USS) Hancock and ordered air strikes in North Vietnam. We on the USS Ranger were going to attack an army barracks at Dong Hoi, North Vietnam. They told me, ‘You are going to lead the strike.’ We were taking a sky full of planes,” he said.

That was the U.S.’s first strike against North Vietnam, and Sells was first in line.

According to Robert Dorr’s book Air War Hanoi, Operation Flaming Dart included 49 aircraft from the USS Coral Sea and USS Hancock and 34 planes from the USS Ranger, Sells’ ship. It was the beginning of U.S. night bombing, so visual location of targets was not easy.

“I got to where I thought Dong Hoi was and dropped my bombs and said to the others, ‘You boys come on in.’”

U.S. bombs and the stored ordnance “blew a hole a mile wide and a mile deep” in the ground, Sells said.

“We didn’t lose a plane. When we got back to the carrier, Walter Cronkite was there and asked me a lot of questions. There was a lot I couldn’t tell him, of course. The next morning, we received a message from Washington: ‘Did you tell him this? Did you tell him that?’

“He made up what he wanted the story to be. From then on, I recorded all interviews. They were there with their recorders, and I was there with mine,” Sells said.

“On our ship we used ‘Spad’ prop planes,” he said, officially the A-1 Skyraider. The Spad nickname came from the French World War I plane.

For his service in Vietnam, Sells received the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bronze Star.

As wing commander on the Ranger, he had gone as far up as he could go as a pilot. “I had gone to the top,” he said. His future path was in ship command. “When I went on my last flight, all the Marines on board saluted me,” he said.

His first ship as a ship commander was the Mauna Kea, an ammunition boat that serviced the carriers of the 7th Fleet. It had a crew of about 300.

“I always told the men what I was doing, and I knew them by name.

“Eventually, the 7th Fleet admiral selected me to be his operational staff commander. I only slept from 1 to 3 am and spent afternoons in the war room,” he said. “I had the job I wanted. I had gone all the way from the first strike in Vietnam to control of all the ships in the fleet.”

He went on to command a naval base in Japan. But, he said, “the worst part of my life came when I was commander of the Alameda Naval Air Station in Oakland, Calif.

“We were just four miles from Berkeley University, which had the biggest bunch of antiwar hippies,” he said. “I had three carriers rotating in and out of the base, and every time one went out, (demonstrators) went out in boats, trying to keep (the carriers) from going to sea. There wasn’t a day I wasn’t harassed.”

One day, he went to a government building off-base to consult with Coast Guard officials. The steps of the building were filled with demonstrators. When he tried to enter, Sells was surrounded by “this bunch of hippies. My hat got knocked off, and when I bent to get it, someone kicked me. When I stood, a woman spat in my face.”

“To hell with you,” he thought.

He turned around, abandoning his meeting, and told his driver to take him back to the base.

“I wrote my letter of resignation right then,” he said. “I was so disgusted. That’s how I ended my career.”

In retirement, Sells looks over letters he has received from officers and high officials, even the secretary of the Navy, but the ones that mean the most to him are from the “little guys” who served under him.

After his retirement, he and his wife moved to Lake Charles and later to Kerrville to be near their daughter. Since his wife’s death, he has lived alone in his home in a neat subdivision in Kerrville.

The veterans of the Mauna Kea thought so much of him that they held one of their reunions at San Antonio so that it would be near Sells’ Kerrville home.

Comments are closed.