After 51 Years Of Military Service, Career Work And Health Struggles, Al Cochran Claims His Second MSU Degree

By Brad Goins

At McNeese State University, there’s a select group of graduates who are called the Golden Scholars. The Golden Scholars are those who get a degree at McNeese, and then, 50 years or more later, get a second degree from the school.

The Golden Scholars always lead the graduation procession. They sit on the front row during the ceremony.

This year, only one Golden Scholar will actually be heading up to the stage to receive a degree. His name is Al Cochran. And he first graduated from McNeese 51 years ago with a civil engineering degree.

At a much younger age than most students, he knew he wanted to study civil engineering. “Even when I was very young, people would ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up. I said, ‘a civil engineer.’ I didn’t even know what a civil engineer was.”

Cochran believes that what he was thinking about at the time was people making bridges. He recalls that the building of the Calcasieu River Bridge had a profound effect on him. (The bridge was built between 1949 and 1952, when Cochran was nearing his 10th birthday.)

First Degree

Cochran began his work on his first degree at McNeese in 1960. He recalls an institution that was markedly different from the one that exists today.

“The curriculum was much harder,” he says. “The grading scale was different, too.” To get an A, students had to score a 93 or higher. “You could not make 60 and pass.

“Professors are much more friendly now,” he says. “They’re very helpful. [In the early ‘60s] they would help you if they just had to.

“Today, I observe college as a business. They can’t afford to lose a single student. Back then, they didn’t think twice about flunking you out.”

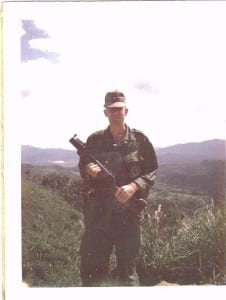

Vietnam

After graduation, Cochran began work as a civil engineer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Vietnam. As he helped build structures for the military, he sometimes came under fire from the Vietcong or North Vietnamese Army. Civil engineers in Vietnam could defend themselves — and even take the offensive if that action seemed to be called for.

But their engineering work was always considered their top primary. For this reason, engineers lacked many of the machine guns and other beefed-up forms of firepower that they needed to go on the offensive.

Cochran learned the practical effects of this situation in a sobering manner when his group of engineers was obliged to go on the attack during the Tet Offensive of 1968. The battle unfolded around the city of An Khe in Vietnam’s central highlands.

Cochran’s engineers fought alongside the “montagnards” — the “mountain people,” who were sympathetic to the cause of South Vietnam. These mountain people were what the U.S. Army considered “Civil Irregular Defense Groups,” or in other words, “paid mercenaries.” As far as fighting ability went, Cochran considered them far superior to the South Vietnamese regulars.

Much of Cochran’s later anxiety about his war memories was due to the fact that he was among the group he calls “paddy rats” — people who were obliged to perform work in the paddy fields even though they came under fire as they did.

One of Cochran’s major accomplishments in Vietnam was to take a lead role in the construction of a 2,000- foot air strip in Vinh Thanh, which was not far from the An Khe fighting grounds.

Cochran, a lieutenant at this time, led the Earthmoving Platoon, which managed to move 140,000 cubic yards of fill and 85,000 cubic yards of waste.

One of the biggest obstacles in the task was a troublesome rock formation, which was only eliminated with the explosion of 15,000 pounds of military dynamite.

The completed airstrip served C-123s and Caribous.

Career

After he returned from Vietnam, Cochran found that in spite of his preparation at McNeese, he couldn’t get a job as a civil engineer.

So he went to work for the Slumber J Oil Co., using the military training and experience he acquired in Vietnam to do explosives and demolition work. While it wasn’t engineering, Cochran found that he enjoyed the job.

He spent the last decade of his working years with an engineering firm. “But I never did get to build a bridge,” he says.

Anxiety

When Cochran retired from his engineering stint in 2001, he didn’t know he was about to be hit by overpowering waves of anxiety generated by his untreated post-traumatic stress disorder. For more than 30 years, he’d used work as a way to keep the anxiety at bay.

“I used my employment and work ethic as self-medication for many years to suppress my experiences while in Vietnam.

“We can get to the point where we can suppress just about anything. When we can’t keep it suppressed — [all of a sudden,] it’s there.”

During the first seven years of his retirement, Cochran managed to keep his anxiety tamped down enough that he could live with it. But in 2008, he decided he could no longer sustain the status quo, and turned to the V.A. for help.

They sent him to Waco, Texas, where he became part of a PRRP — that is, a post-traumatic stress residing rehabilitation program. He learned such behavioral coping skills as exposure.

Cochran felt that the PRRP made a world of difference, and he wants vets to know that what worked for him can work for them. “Help is available. It’s very good help. You’ve just got to ask for it.”

He eventually settled into a treatment program that includes medication, group therapy and individual counseling.

Education As A Coping Skill

Cochran made a huge stride forward in his battle against anxiety when he hit on the idea of returning to McNeese in 2012 and taking courses in photography.

“I was just searching for something that would divert my attention from intrusive thoughts,” Cochran explains.

A therapist had earlier suggested that Cochran take up both genealogy and photography as ways to block out the unwanted thoughts that come with intense anxiety.

In his McNeese classes, says Cochran, “I can focus on what [the professor or instructor] is talking about.” The process works well to keep Cochran from thinking about himself and his intrusive thoughts. “It’s a coping skill.”

And he discovered another benefit to his class work. “I really enjoyed it.”

Cochran found that his unusually good memory of his class work from half a century before aided him in his second round of studies.

“I was well prepared compared to a new student.” In his first run at McNeese, he finished 29 hours in math, working his way all the way up through vector analysis. “It was a very good education.”

When Cochran returned to McNeese, he didn’t experience any of the awkwardness that’s a dominant motif in comedies about students who return to university studies at an advanced age. “I [always] sat on the front row,” he says. “It was very congenial.” He learned that the other, younger, students would “even try to pick information out of me.”

Cochran came to see his return to the class as a kind of competition. “It was interesting competing with those youngsters. I found out I could compete with them. I didn’t think [at first] I could.”

Full Circle

Cochran’s latest enthusiasm is for the criminal justice courses he’s taken in the course of getting his second degree. Even after he gets his second bachelor’s this May, he’ll take more courses in the subject.

“It’s interesting to study how police do their work in catching criminals. They’re much more organized than I thought they were.”

But Cochran thinks the day when he’ll quit taking courses is fast approaching. “My health is not good,” he says.

And in fact, it was his health that was the biggest obstacle in his quest for a second degree. During his course of study, he had to undergo seven weeks of chemotherapy when he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. Not long after he recovered, he underwent open heart surgery.

When his course work is finally completed, Cochran does plan to continue to serve on the Lake Charles Mayor’s Armed Forces Commission, where he works as a veterans’ advocate.

When Cochran takes stock, how does he see his life? He’s been a degreed student, an engineer under fire, an infantry fighter, a demolitions worker, a photographer, a cancer patient, a recipient of open heart surgery, a veterans’ advocate and a degreed student for a second time.

Does he feel that’s he done about everything there is to do; that he’s run the gamut?

“I don’t think there’s much more I can accomplish,” he says. “I’m about done.”

It certainly has been a full life.

Comments are closed.