What The Media Are Not Telling Us …

I am writing this column on Sept. 11, twenty years after Al Qaeda terrorists flew planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, killing 2,977 people. Following that attack, the United States invaded Afghanistan in search of Osama bin Laden, the leader of Al Qaeda, and to make sure that Afghanistan could not be used to launch other terrorist attacks against the U.S.

Why did our effort to reform Afghanistan fail? It has been my observation over the years that when one scrapes away the veneer of good intentions and noble goals, one finds economic interests are at the core of most wars and conflicts, and Afghanistan is not an exception.

Afghanistan is one of the most impoverished places on earth. It is a mountainous, landlocked country with 32 million people and a gross domestic product (GDP) of around $70 billion a year. On a per capita basis, it ranks 210th out of the 225 nations in the world. When our forces arrived in Afghanistan, the country was already in shambles from constant wars. Why were people fighting over this pile of rocks? The media told us the wars were about religion, but there was an economic reality they tended to overlook.

Afghanistan produces more than 90 percent of the illegal heroin in the world. Poppy fields are planted throughout the country; opium gum is extracted from the poppies and dried into a resin that is used to make heroin that is then smuggled into southern Europe through Turkey and the Balkans, or into Russia and northern Europe along what is known as the “smack track” in central Asia. The production and transport of illegal heroin is estimated to employ 400,000 workers and accounts for 11 percent of Afghanistan’s GDP. (By comparison, the entire agricultural sector in the United States accounts for less than 10 percent of our GDP.)

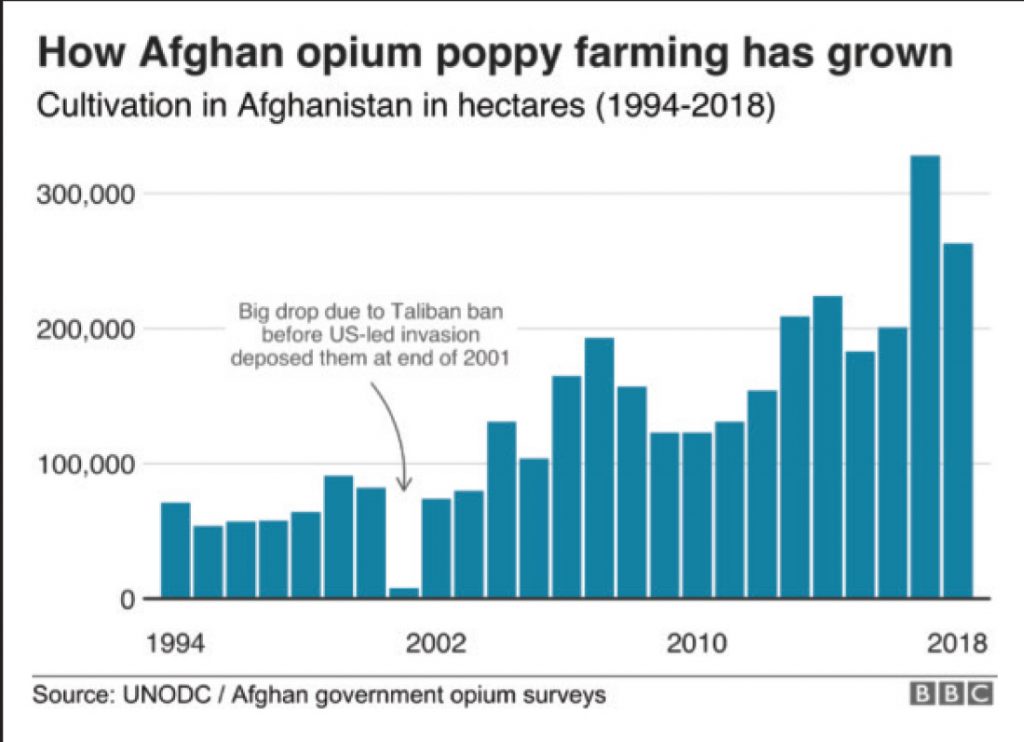

When Russia pulled its forces out of Afghanistan in 1989, it left a power void and the country was torn apart as rival warlords fought to control the opium trade. In 1994, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia created the Taliban to restore order and impose strict sharia law. When the Taliban seized Kabul in 1996, it declared drug production un-Islamic and in July, 2000, it imposed a ban on poppy farming that it enforced with eradication, confiscation and public punishment of transgressors. The result was a 99 percent reduction in poppy farming and opium production in the areas controlled by the Taliban.

The success of the ban brought the Taliban praise from the United Nations and the U.S. at the time. But it angered the drug lords and the 400,000 workers who depended on harvesting the poppy crop. Thus, when the U.S. sent its troops into Afghanistan to overthrow the Taliban a year later, it found many willing allies in the poppy-growing regions. They were not excited about getting to vote in democratic elections or their daughters being able to attend school; they were excited about getting to plant their poppies again and re-starting the heroin trade to which many officials in the new government were willing to turn a blind eye.

The table on the opposing page shows the result: there was a 400 percent increase in illegal drug trafficking during the 20-year US occupation.

As I contemplated writing this column, I asked people if they were aware that Afghanistan was to Europe and Russia what the Central American drug cartels are to the U.S. No one I spoke with was aware of Afghanistan’s illegal drug trade. “Why?” I wondered. It was not a secret. Our generals in Afghanistan were aware of the drug trafficking but did not believe drug interdiction was part of the army’s mission.

Once the Taliban was out of power and unable to control the cultivation of poppies, they decided taking money from drug traffickers was not un-Islamic, and “taxes” collected from drug traffic in areas they still controlled became a major source of funding for their war against the government in Kabul. The U.S. military did launch some highly publicized airstrikes against opium factories in areas controlled by the Taliban in an effort to deprive them of this revenue. But the military looked the other way when it came to drug money going into the pockets of officials in Kabul.

It is tragic, but one of the main beneficiaries of our 20-year occupation of Afghanistan was illegal drug trafficking. I am not suggesting the U.S. military or U.S. officials were directly profiting from illegal drug trafficking; rather I believe it was the unintended consequence of well-intended policies that came about due to a failure to recognize the economic realities of the region.

P.S. I must acknowledge the passing of another good friend of mine, A. D. Ballard. A.D. and his wife, Connie, were long-time members of our Mardi Gras krewe in Moss Bluff. He had a pipeline maintenance business, and after he retired, he travelled around the country as a consultant. He was a good man who loved the outdoors, loved his family and enjoyed a good joke. Rest in peace, ol’ buddy.

Comments are closed.