James Johnson Has Learned How To ‘Move Forward’ In Spite Of Major Adversities

By Brad Goins

Fr Johnson, the new millennium brought the birth of a daughter. When Gracie was three, her parents were con-cerned because she had an ear infection and fever that didn’t seem to be going away. The child was taken to the ER. The doctor took a blood test and found that Gracie’s white blood cell count was, in the words of her father, “super high” — at 180,000 cells. (A nor-mal count is 4,500 through 11,000 white blood cells per mm3.)

The doctor said he felt it was likely Gracie had leukemia, and suggested a quick trip to Houston or New Orleans. Gracie was driven to Houston in an ambulance the next morning.

“Our whole world kind of collapsed,” says Johnson. Gracie began a two and a half year-long regimen of chemotherapy. When that was over, she underwent eight days of the rigorous treatment of cranial radiation. She was only six years old.

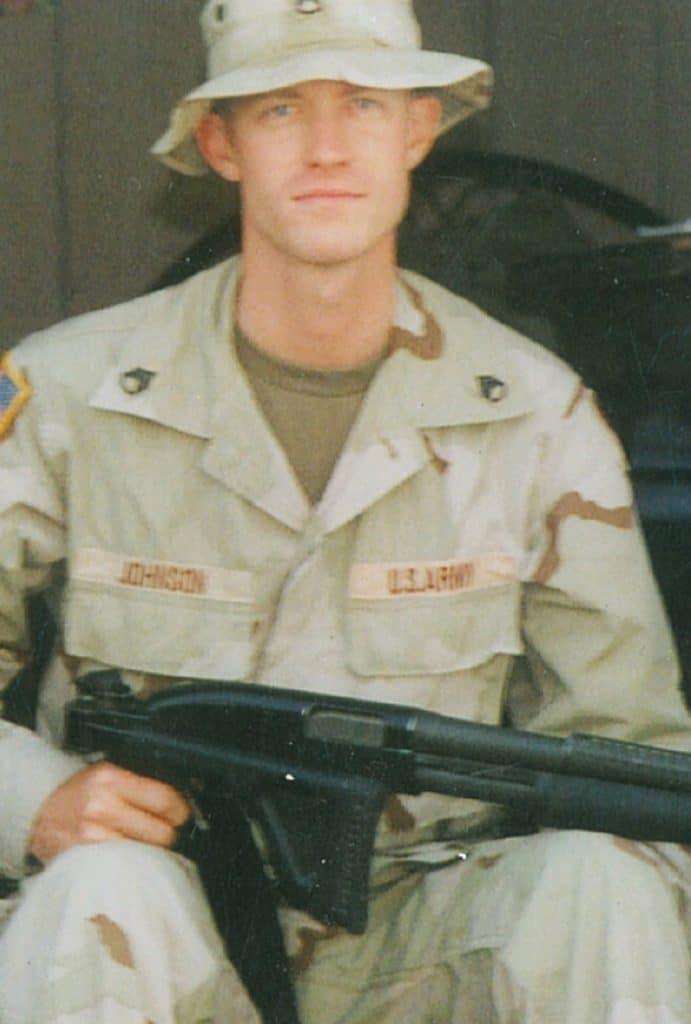

Under Fire In Iraq

In May, 2004 — seven months after his daughter was diagnosed with leuke-mia — Johnson was deployed to serve in Iraq. At the time, all 4,000 active mem-bers of the National Guard in Louisiana were sent to the war-torn country.

Staff Sgt. Johnson arrived in Bagdad as an infantry squad leader. He and his people had the job of patrolling Bagdad while being on the lookout for any un-toward behavior. Opposition groups in the city were taking actions to challenge the free elections that were about to take place in the city. (The voting would even-

tually receive international coverage that focused on the purple ink that was put on the fingertips of those who’d cast ballots.)

Johnson says the U.S. troops were “mortared every day. Bagdad was defi-nitely a dangerous place” at the time. But soldiers at least had the consolation of feeling they were part of something significant. “It was an interesting time in history,” says Johnson.

One day in January, 2005, Johnson and the others in his group were travel-ling down a road in two Bradley Fighting Vehicles that moved by means of large and tremendously loud tracks. The troops were crammed into the machines. Johnson sat with his back to the front of the vehi-cle; he was back to back with the soldier sitting in front of him. Johnson faced a large metal plate that rose up from the ve-hicle’s floor. The sounds of the vehicle’s treads were so loud he could not talk to the person behind him or in front of him.

Then, says Johnson, he heard a “pop.” Suddenly the vehicle was shot through with blistering light and an ex-plosive burst of sound. The Bradley had run over a handmade IED (or improvised bomb) that had been placed under dirt in the road.

The blast killed two soldiers immedi-ately and seriously wounded four others. The man who’d been sitting with his back next to Johnson’s was dead. The vehicle was destroyed. Johnson was rendered un-conscious.

The force of the blast threw him into the sheet of metal in front of his seat, giving him a deep cut on the head. The butt of his rifle struck him on his chin. Although he didn’t realize it at the time, his right knee had been broken, and his back had been broken in four places.

When he came to, Johnson says, he “didn’t know [he] was hurt, but [he] knew [he] had to get out of the vehicle.” He had the sensation of being unable to breathe, no doubt due to the abundant smoke and fire in the vehicle.

The driver had enough presence of mind to operate the switch that opened the hatch and lowered the ramp at the back of the vehicle. Johnson was able to escape. Once he was safe, he stopped to pull a sol-dier from the wrecked Bradley. He would later realize this man was already dead.

Johnson’s training kicked in. He took cover against the possibility of an enemy attack. “IEDs are there for a purpose,” he says. Enemy fighters often attacked after an explosion. In this case, it turned out the U.S. soldiers would be spared a follow-up attack.

It’s probably just as well that Johnson was operating on adrenaline during these frightening moments. Had he realized the extent of his injuries, the shock might have left him immobile. “I was just react-ing,” he says. “It was a blur.”

Injuries And Recovery

“Once the pain started, I knew things were bad,” he says.

In addition to suffering broken bones, Johnson’s throat and vocal cords were badly burned by the fire and smoke. Eventually his throat swelled shut. When he was flown to Brook Army Medical Center in San Antonio, he was put on a ventilator. He remained in a coma for a week.

When Johnson came to, he had a “very difficult time talking.” He was “super hoarse.” He “most definitely felt [the pain in his] back.”

For a year, Johnson remained in the center, undergoing a course of extensive physical therapy. While he was a patient in Brook, Johnson says, he “received the best medical care you can possibly imag-ine.”

One thing that Johnson learned some time after the explosion was that he had suffered an “incomplete tear “ in his spi-nal cord. Doctors told him that even when he recovered, he could expect to spend half his time in a wheelchair. And for a time, he did “spend a lot of time” in one — especially when he wanted to “go any distance.” But his goal was to — eventually — never be in a wheelchair.

The spinal injury caused a loss of feeling in Johnson’s extremities, as well as a significant loss of fine motor skills. With his determined approach to physical therapy, he would eventually overcome these problems.

He had also suffered “traumatic brain injury,” which, for a time, had a negative effect on his short-term memory.

These limitations imposed severe restrictions on the number of basic, practical tasks that Johnson could perform. The act of putting a key in a lock, for instance, was extremely challenging. Doctors had to put a special covering on Johnson’s keys so that he could effectively manipu-late them. It is frustrating, he says, “when all of a sudden you can’t do something you usually do.”

Dealing with the level of pain was a formidable challenge. “It felt like a giant had crumpled me up and thrown me on the ground,” says Johnson.

He estimates that it took him eight years to fully recover from his injuries. That was especially the case with walk-ing. Now he can go all day without sit-ting in a wheelchair. In fact, he says, he hasn’t used his wheelchair in years. He still walks with a limp if he’s tired or has had a long day.

Johnson says he “always felt he would make it” to complete recovery. “It was too important” not to. Still, he admits, there was plenty of discouragement. And challenges remain. The torn spinal cord, he says, “won’t go away” — not ever.

These days, Johnson continues to work for the National Guard, though not, of course, as an active soldier. His injuries were so extensive that he was medically retired from the Guard. For 10 years now, he’s been working for the National Guard as an education liaison in conjunction with recruiting.

One Thing After Another

Almost a year after Johnson was wounded, his daughter Gracie suffered a relapse. Johnson says “it definitely felt like one thing after another” was hitting him.

But once the relapse had been dealt with, his daughter appeared to be cancer-free for a decade. Gracie seemed to have fully recovered. She was up to going back to school, where she excelled in her studies.

She made it to her senior year of high school at Hamilton Christian Academy. One day, in 2018, Johnson received a phone call from a concerned staff mem-ber at the school. Gracie had apparently had a seizure. Follow-up revealed that she had a brain tumor. Years earlier, doctors had told Johnson there was a small chance such a tumor could one day develop as a result of the cranial radiation.

Gracie immediately resumed the ra-diation treatments she thought she had left behind. But things didn’t go as well as they might have. After a time, the primary doctor told Johnson that his daughter’s brain tumor was “inoperable, incurable, terminal.” But Johnson says that “through all of that I never accepted it was terminal.”

Gracie stayed in Houston for six weeks getting treatments. Then she brief-ly returned to Lake Charles in spring to go to her high school graduation and make a speech. She had been named valedicto-rian of her class.

Her fellow students, Johnson says, “were amazing” and “super supportive … they were all wonderful … It was a close-knit group.”

Gracie succumbed to her long disease in October of last year.

The loss of a child, says Johnson, “is a nightmare for any parent.” When he speaks of the series of ma-jor adversities he’s lived through, he says, “It’s like telling a story about somebody else. It’s like I’m watching it. It’s a movie. I’m sure it’s the brain’s way of coping. of “getting [his] house extremely torn apart.”

“Difficulty in life is inevitable,” he says. One is certain to experience “major tragedy or loss” from time to time. It is wise to “train ourselves to prepare” for major losses and setbacks and disappoint-ments.

How To Change The Weather

James Johnson recently published the book How To Change The Weather. The volume is a collection of autobio-graphical essays.

How did the author come up with such an intriguing title? Johnson long had a strong aversion to being in the rain. But once he was on the field of battle in Iraq, he found he was in rain a great deal. And eventually, he grew used to it. “You build your endurance to things by adapting to things,” he says.

His book is about the ways in which people respond to adversity.

Recovery from adversity is never absolute. After the loss of a child, says Johnson, “you’re never going to move on. I don’t say I’m moving on. I’m moving forward.”

Writing the book was “cathartic,” says Johnson. “It’s short on purpose. People are busy.” He wanted the language to be conversational and accessible. He wanted the content to be helpful.

“I don’t say any of this to get pity. I want people to [get] inspiration and motivation for what they’re going through.” He wants to “instill a message of hope.”

“I’m pretty obstinately optimistic. I will be optimistic no matter what.”

Comments are closed.