By Madelaine B. Landry

My father left us in 1980, too young at age 62. Daddy wasn’t a wealthy man; so mostly what he passed on to his children could be shared, not spent.

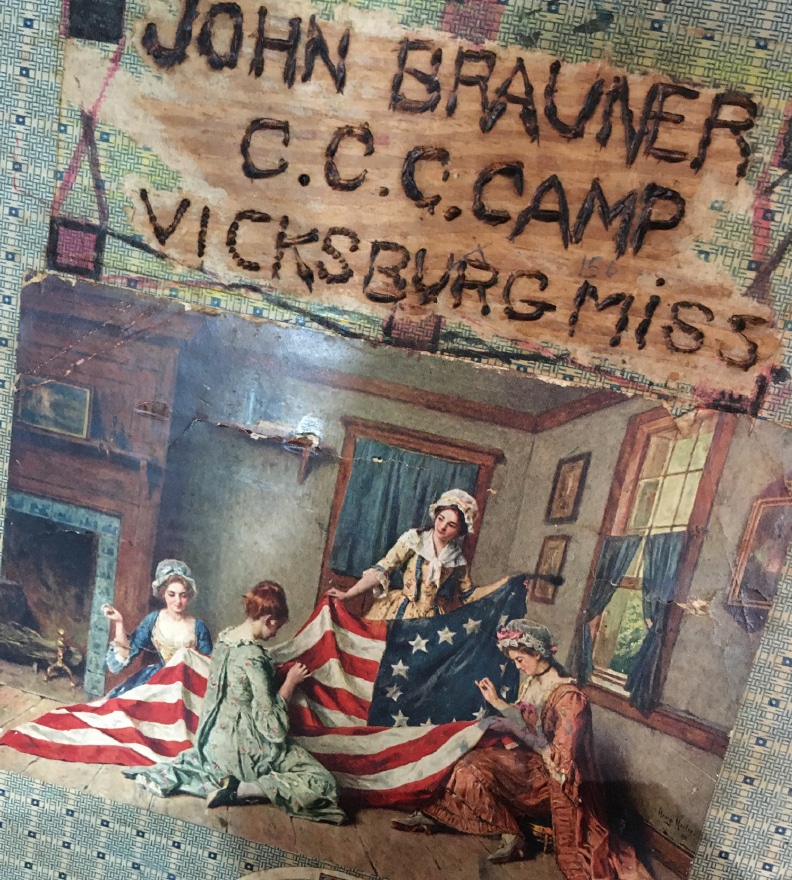

As kids, when daddy opened the trunk, we anticipated fireworks, magic. Opening it today, there’s mystery. Violet, our mother, always laughed about the photos and missives from daddy’s old flames. He’d scribbled many flirty and heartfelt sentiments to Mafalda, Ursula, Joan and some other Violet who preceded mama. My folks didn’t date and marry until well after he returned home in November, 1945.

“I was 28 on our wedding day. I didn’t have much use for a 35-year old virgin,” she quipped.

It wasn’t often, but when daddy spoke of the Italian women he’d befriended, I expected photos of Neapolitan beauties like Sophia Loren or Gina Lollobrigida. Instead, they demonstrated his preference for the buxom, blonde beauties from Northern Italy.

“The mothers of the women I knew trusted me because I looked like one of their own,” daddy once explained. He ran into trouble once when one asked “antipatico o simpatico?” He picked the wrong one, but quickly realized his error. “I was more careful after that.”

Mama found him simpatico. “He ended up with a skinny woman of French descent from his hometown,” she’d say with a smug grin. “I’m the one who captured him; that makes me the winner.”

They both won. When he died shortly after their 25th wedding anniversary, she buried him with a small bouquet of violets tucked in his hands, next to his Rosary. She never considered dating or remarrying, though I can’t imagine she didn’t have offers. Until she died 15 years later, she remained his “baby,” and he, her “honey.” We seldom heard them call each other by their given names.

Of course, daddy’s mother had a different take on daddy’s romantic carrying-ons. The Irish and Italian immigrants in New Orleans historically had been rivals in the early 20th century, fighting for the same jobs after arriving in the port city. Of German-Irish descent, Grandma remained distrustful of Italians during the war era. Two of her sons served in Italy — daddy in the Infantry and his brother, Charles, as an Army medic. When they returned home, she told them she’d prayed daily to the Blessed Mother not only for their safety, but also that they’d not come home with Italian war brides. Daddy gently explained that the Italian mothers felt the same.

He also solaced his mother with two 8 x 10 black-and-white photos of GIs attending Mass. It was important to him because it was important to her. I found them in the trunk in an envelope addressed to the mother he idolized, along with his nine siblings. The number of prayer cards he kept is evidence that Grandma and her sisters offered many Masses for their boys overseas. The prayer cards are testaments to the faith that sustained them through the war years.

I discovered the following analogy about memories online a while back. I jotted it down in a notebook, without attribution. I must’ve known it would come in handy one day. “Retrieving a memory might be a bit like taking ice-cream out of the freezer and leaving it in direct sunlight for a while. By the time our memory goes back into the freezer, it might have naturally become a little misshapen, especially if someone has meddled with it in the meantime.”

For over four decades now, my three siblings and I have talked of reserving a day when we could take the “ice cream” of memories from the freezer of time daddy left behind. We each remember details differently when we talk about the trunk’s items. Are we recounting things that we believe to be true or wish were true? We easily point out the embellishments or tiny flaws in each other’s recollection of past events. And, isn’t it just human nature to use some artistic license as we tailor our tales to our audience, hoping to get a laugh, a tear, a nod of agreement? It’s called the audience-tuning effect, this inclination to describe our memories differently depending on who’s listening. Not only do our stories change, but so do the memories themselves, which have been meddled with and misshaped.

You see, our father was a storyteller extraordinaire. When he’d tell us tales about B’rer Rabbit, B’rer Fox and B’rer Bear, each character got a distinctive voice, funny quirks, different facial expressions. We’d gather around his chair to hear how Rabbit disingenuously begged not to be thrown into the Briar Patch, how he ate all B’rer Fox’s huckleberry jam and earned ‘leventy-’leven dollars and ‘leventy-’leven cents for minding his goober pea patch.

Sunday mornings were reserved for donuts and daddy “reading” the comic strips. Hatlo’s History, Dagwood Bumstead, Lil’ Abner, Gasoline Alley … he described them pane-by-pane to us, less a reader than a raconteur. Later, at Mass, the donuts made me drowsy, so I’d dream I was Prince Valiant’s maiden-in distress or one of the Katzenjammer Kids getting into mischief. It was hardly surprising to find many faded comic strips in his trunk.

Daddy was also a joke-teller, relating naughty, slightly off-color jokes to amuse adult friends and select family members. (Read: never his sisters or mother!) They’d sit around the kitchen table, drinking cup after cup after cup of strong coffee and chicory. No children allowed. My younger brother sneaked outside once, standing under the kitchen window to eavesdrop. Off course, the jokes went well over our innocent heads, but we caught him off-guard later by casually asking: “So, daddy, what did the barber say to the policeman?”

Daddy trained to be a Radio Operator in Tyler, Texas, where, as family lore has it, he opted to take telegraphy courses rather than attend Officer’s Training School. Made sense. He was self-deprecating and humble; he would’ve never consented to outranking his Army buddies. “The Rose Capital of the South” — he loved Tyler so much that he and my mother honeymooned there in 1952. While there, he shipped dozens of roses home to his mother, sisters and aunts. Did I imagine he said, “A dozen bouquets made up of a dozen roses for less than a dozen bucks?” A frugal man by necessity, still, I doubt that cost would’ve much mattered since family and flowers were two of his many passions. Beauty impressed him deeply, whether in nature, song or the female form. Need it be noted that his trunk also contained an inordinate number of WWII-era pinup photos?

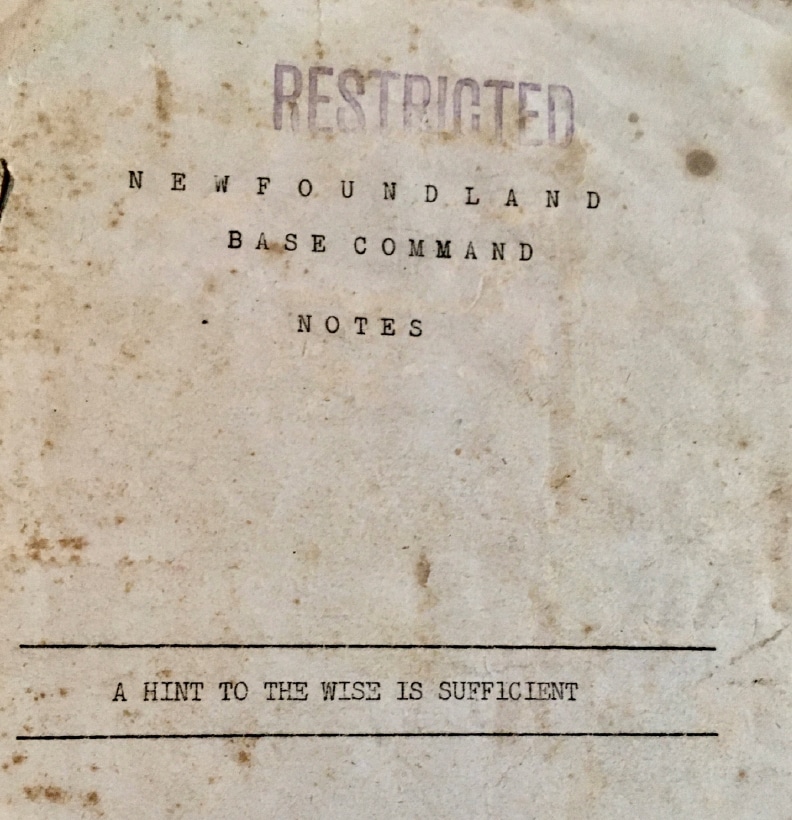

From Texas, he left for camps in New York and Massachusetts before ending up in St. John, Newfoundland, in 1943 for AEME (Africa, Europe, Middle East) battle training. Upon arrival, each GI received a Restricted book entitled “Newfoundland Base Command.” The typewritten pages contain the usual memos to enlisted men. Warnings about “loose lips,” uniform regulations, base church services and euphemistically, how to locate the Base Prophylactic Station “…if you find it necessary to partake of products not government inspected.” Number 21 notes that “marriage by members of the command are not looked upon with favor.” Number 18 is particularly amusing:

“Due to unsanitary conditions, the following cafes and beer shops are permanently placed off limits and will not be patronized. Liquors served in these beer shops frequently lead to temporary insanity.”

He returned stateside in time to ring in the New Year of 1944, but there’s no record of other training before he was shipped to Naples, Italy, on a troop ship in February 1945. In a tiny notebook, in neat, cramped penmanship, daddy listed every Italian village and town he went through as a soldier in General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army. For the Po Valley and North Apennine campaigns, the troops traveled northward through Rome, Florence, Lake Garda, Lake Como, Verona, Veneto and Trentino before departing from Bolzano in late August. Seven months until he bumped up against the borders of Austria, Germany and Switzerland, and yet daddy recorded not one word about the fighting! He was one of those WWII vets who took those recollections to the grave. The only indication of fighting he witnessed can be found in a three-page, hand-written note entitled “The Most Unforgettable Character I Knew.” Describing an elderly woman in “an obscure and antique village in Northern Italy,” he details her courage and fearful eyes as she peddled her grapes and cherries “in the midst of spasmodic, if not heavy, fighting.

“But war put fear in those eyes: fear perpetrated by incessant bombing of the town, of seeing loved ones die … She would duck for cover on an approach of a friendly plane, then fall in prayer on learning it was not over the town on a mission of death.”

It feels surreal at times, touching what my daddy once touched; organizing these memory cues. Sifting through souvenirs, some poignant and others provoking more questions than answers. Reading the lines written to, and answered by, his many correspondents before he was ever a husband or father. I feel like a detective following cold case leads that defy connections. Scanning photos of places and people that no longer exist, many unidentifiable —these snapshots in time become snapshots in our time to contemplate.

What to do with these treasured scraps from a man we knew to be at times sentimental, witty and irreverent? A loving son, husband and father, and certainly not a risk-taker. Family, culture, the Great Depression and WWII formed him that way, as it did so many in his generation.

Still, all these decades later, his trunk closes on one truth we know he knew full well: love and life and beauty and kisses and music and prayers and laughter and tears — these make the risks worth taking. Each of these things brings moments worth cherishing … and rescuing.

Comments are closed.