The Case Against Multiple Choice Tests

I taught a lot of students in my 30 years at McNeese. On two separate occasions last month, a former student introduced himself. Both said, “and I still remember how airplanes fly.” That may seem like a strange thing to say, especially since I taught economics, but it came from my lecture on the first day of class. Here is the story behind that greeting.

I was an “old school” professor when I arrived at McNeese in 1984. I didn’t give multiple-choice tests; I only gave three essay tests a semester — two midterms and a final. This was a lot of extra work for me. Most textbooks come with an instructor’s manual that has a test bank full of multiple-choice questions. The instructor simply downloads the questions he wants and prints out the test; then the students put their answers on a scantron sheet which the teacher runs through a scantron reader. The whole process takes about an hour.

After a few years, several students went to the dean and complained about my tests, claiming they had not been taught in high school how to answer essay questions. The dean sympathized with them, and informed me that I had to include multiple-choice questions on my exams. I agreed to include some multiple-choice questions about vocabulary on tests, but continued to require students to explain, in writing, the principal concepts of economic theory.

But because of their complaints, I decided I needed to explain to the students what I was trying to achieve and why I required written answers. Thus, I began spending the first day of class with a general discussion with the students about learning. Those who had been home-schooled or attended a private school generally had no problem with written tests. But many public school students confirmed that they had never had anything other than a multiple-choice test. (This was 25 years ago, so it may be different now.)

Many students also confessed that they seldom read an entire chapter of a textbook; they just took the study guide their teacher gave them and looked up the answers. They then sat up all night memorizing the answers. They agreed that if they were given the same test two days later, they would fail it because they would have forgotten everything they had memorized. Judging by the nodding heads, they agreed this was a game and they were not really learning much.

I then explained that my approach to teaching was different. I focused on concepts. To illustrate this, I asked the students how many of them had flown on an airplane (nearly all raised their hands). Then I asked how many knew what kept the airplane in the sky. (I usually had two or three engineering students who knew the answer, but most had no clue).

I would then explain that even though we cannot see air, it is a substance, just like water or soil. We can see water, so we know what happens if someone takes a bucket of water out of the lake: the surrounding water quickly flows in to take its place. Although you can’t see air, the same thing happens with it: if you remove all the air from some place — what’s called a vacuum — the surrounding air tries to fill in the space left by the missing air. Take all the air out of a soda can and it will crumple up as the surrounding air tries to force it way inside.

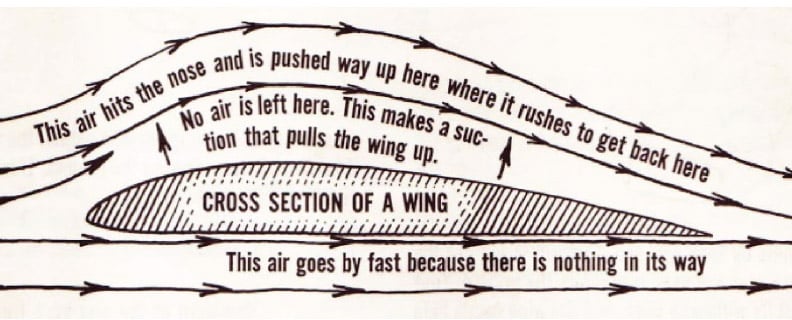

I would then draw a diagram similar to the one that accompanies this column and explain that the shape of the wing is what makes an airplane fly. As a plane moves forward, the shape of the wing creates a vacuum above the wing and the air below the wing tries to fill that vacuum the same way it does with the soda can. One might think that air cannot be a strong enough force to lift a big plane off the ground. But there are 2,116 pounds per square foot of air pressure pushing the wing up.

I would also point out that no matter how fast the plane is flying, if there is wind sheer from a storm, it can mess up the vacuum and cause the plane to drop like a rock until the vacuum is restored. (I was on a flight like that once and it was pretty scary.) If there is ice on the wing, that can also interfere with the vacuum and could cause the plane to crash.

All of this took 10 or 15 minutes to explain. When I was finished, I asked the students how many understood how airplanes fly. (My success rate was usually around 60 or 70 percent.) I then told my students that if they understood this concept, or any concept, they would not have to sit up all night trying to memorize it; they would know it for life … “If you run into me in the post office or some other place 20 years from now, you will be able to say … Dr. Kurth, I still know how airplanes fly.” So I would like to thank those two former students for making my month.

Comments are closed.