Slightly Below Normal Activity Is Likely

By Brad Goins

This year, the experts at Colorado State predict “slightly below normal” activity during the hurricane season. One reason is that the present El Niño weather system is likely to persist, and perhaps grow stronger, during the season. In a few paragraphs, I’ll explain why it is that El Niño wind systems put such a damper on hurricane development.

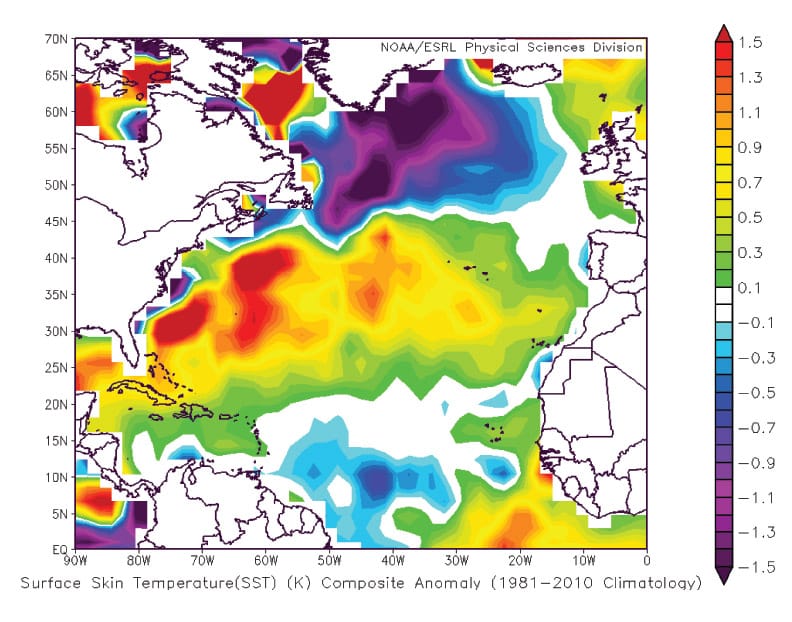

Colorado State is also emphasizing that sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic — where the hurricanes that eventually strike us originate — are cooler than normal. And sea surface temperatures in the north Atlantic are quite cool. Of course, it is warm sea surface temperatures that give birth to storms.

Note there is no hot water off the African coast, where most of our hurricanes begin.

Also taken into consideration was high sea level pressure in the sub-tropical Atlantic. High sea level pressure tends to correlate with strong trade winds. These winds mix up the sea water, bringing the cool water at the bottom up to the top — just one more thing that will likely tamp down storm formation this season.

Will El Niño Hang Around?

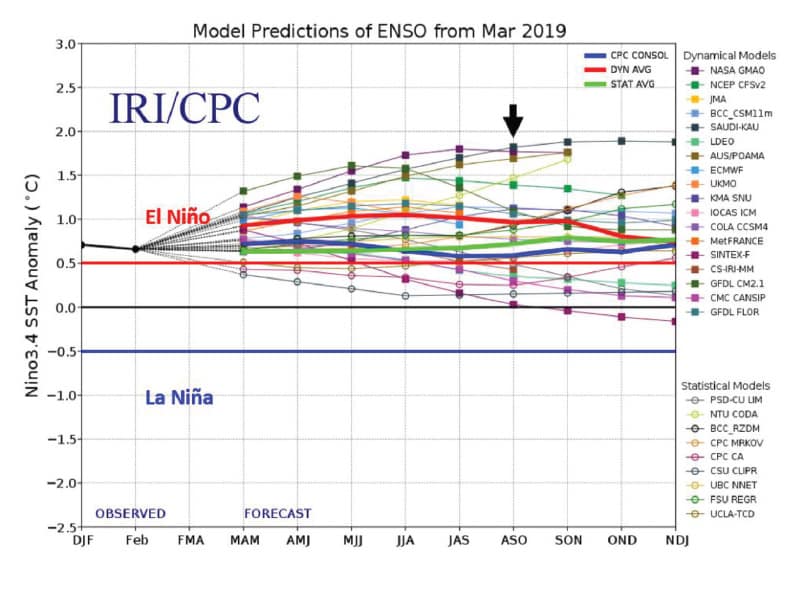

Now, let’s return to that lingering El Niño system over in the Pacific Ocean. Such a system is traditionally associated with a low level of hurricane formation around U.S. coasts.

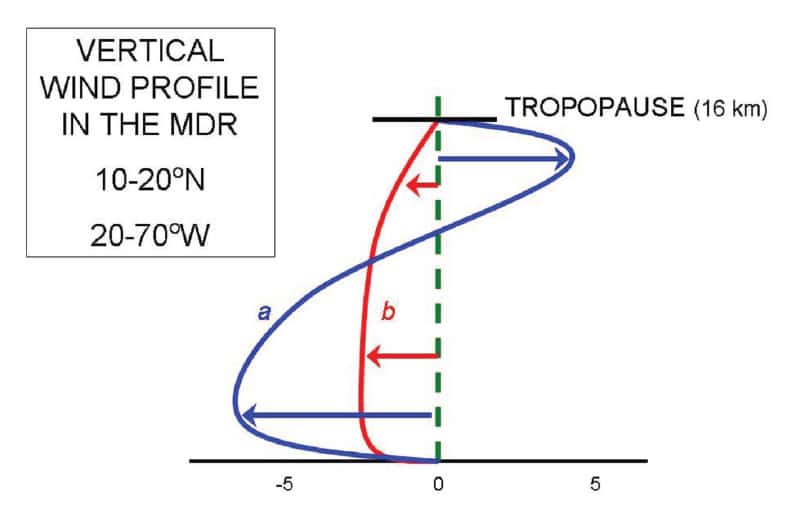

One reason is that El Niño sends a powerful jet stream from the Pacific Ocean right across the Gulf of Mexico. One thing this jet stream does is use wind shear to disorganize the tops of columns of hot, moist air that are turning into storms. When the top of the air column is cut off, the high, spinning wind that powers hurricanes is eliminated.

Strong wind shear in the Atlantic basin (MDR) will mean reduced chances of hurricane formation. The red line shows what is left of the storm after the top (blue line) has been sheared off.

Forecasters at the Weather Channel seem to be in line with Colorado State on El Niño’s persistence this season. “El Niño conditions are expected to persist or, at worst, slowly weaken over the next six months, which should act to help suppress activity a bit,” said Dr. Todd Crawford, chief meteorologist at The Weather Company.

European forecasters are all over the place when it comes to this season’s El Niño. But note that not one forecaster is calling for La Niña.

Long-term European forecasts for El Niño. No one is calling for La Niña.

The Bottom Line

So, the bottom line is a prediction of a “slightly below normal” chance of major hurricanes striking the Gulf Coast this season.

Colorado State’s exact prediction, as of April, is for two major hurricanes and three more, less powerful hurricanes, to develop in the Atlantic storm basin. The fact that the average number of major hurricanes in a season is 2.7 explains the “slightly below normal” phrase. (A major hurricane is one that is Category 3 or higher.)

The Colorado State experts say the chance of a major hurricane striking the Gulf Coast or the East Coast is straight up equal: 28 percent for each coast. The chance of at least one major hurricane tracking into the Caribbean is 39 percent. (Again, this is slightly below the normal chance of 42 percent.)

As for specific locales, Colorado State puts the chance of a major hurricane striking Calcasieu Parish this season at only 0.6 percent. Cameron is about twice that at 1.3 percent.

For purposes of comparison, I always include Galveston — 0.9 this season — and New Orleans, which has a 0.8 chance of a landfall. So, chances are low all around this season.

But the scholars at Colorado State love to point out that however low the chances of landfall may be, if a major hurricane does happen to strike your locale, it will be devastating.

A Work In Progress

Long-term hurricane forecasting is a work in progress. Colorado State is quick to emphasize that no one should take its predictions as gospel truth. “Everyone should realize that it is impossible to precisely predict this season’s hurricane activity in early April.”

Then why issue the forecast? During its 29 years of forecasting, Colorado State researchers have figured out ways to compare data about hurricanes with such accuracy that their forecasts tend to be more accurate than those of climatology (“climatology” meaning the standard, traditional tools of prediction).

It’s stated in the forecast report that “one must remember that our forecasts are based on the premise that those global oceanic and atmospheric conditions which preceded comparatively active or inactive hurricane seasons in the past provide meaningful information about similar trends in future seasons … “

“No one can completely understand the full complexity of the atmosphere-ocean system. But, it is still possible to develop a reliable statistical forecast scheme …”

“It is also important that the reader appreciate that these seasonal forecasts are based on statistical and dynamical models which will fail in some years.”

For those who like more straight and simple terms, historically, Colorado State’s hurricane predictions have been 15 percent more accurate than those of individuals using standard meteorological methods of prediction.

On the graphic at the bottom of the opposing page, the pink line shows the weather that actually took place. The blue line shows the weather as Colorado State predicted it.

For the first time, Colorado State is using a new forecasting model — the ECMWF System 5. The model was developed in collaboration with the Barcelona Supercomputing Centre. This is the most accurate model presently being used by the group. even though its data were calculated in March, it predicts events in the Atlantic in August.

Although this model, when used by itself, calls for a slightly above normal Atlantic storm season, it should be kept in mind that the model also calls for warmer than normal ocean temperatures all over the world. It is when Atlantic temperatures are at variance with temperatures in other oceans that major hurricanes are most likely to arise.

What About 1969?

Another forecasting method used by Colorado State is to analyze past years that have weather conditions most similar to those of the present year. Then it’s an easy task to see how many hurricanes arose in those similar past years.

Five years correspond closely with conditions in 2019; they are 1969, 1987, 1991, 2002 and 2009.

The year 1969 is a bad match; that year saw no fewer than five major hurricanes develop.

We will see later in the story that that troublesome 1969 season will figure strongly in Accuweather’s hurricane forecast for 2019.

But the other four years had below average activity. 1987 had only one major hurricane; the other years had two each.

Colorado State says its models for prediction become more accurate as the hurricane season gets closer. The university’s next hurricane prediction will be released June 4. Unfortunately, this issue of Lagniappe will be at the press on that day.

But you can easily find a summary of the June 4 prediction by going to tropical.colostate.edu and clicking the June 4 Forecast of 2019 Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity at the top of the page. Page 2 of the report that you’ll get will include a simple, easy-to-read table that shows the number of hurricanes and major hurricanes being predicted. Drastic changes in Colorado State’s forecasts are very rare.

Slightly Differing Forecasts

Colorado State researchers are not the only ones who forecast hurricanes. Although no one outside of Colorado wanted to do long-term forecasts in the 1980s, when scientists claimed the process was hokum, today there’s a sizable crowd of long-term hurricane forecasters around the world.

Last year, Lagniappe reported that Accuweather’s Dan Kottlowski had scooped Colorado State in the previous hurricane season. He thought he’d detected a large body of unusually warm water in the Gulf of Mexico that Colorado State had missed. He was right, and the Gulf experienced an active storm season.

This time, Kottlowski is differing from Colorado State again, though not by a remarkable degree. Instead of predicting two major hurricanes, he’s predicting a range of two to four.

Like Colorado State, he’s noting that this year’s weather conditions are very similar to those of 1969, when Hurricane Camille slammed into the Mississippi coast, bringing winds of 175 mph — the third fastest in the country’s history. The similarity of 1969 to this year seems to make Kottlowski take a somewhat gloomy note.

This year, says Kottlowski, there’s an equal chance of a major hurricane hitting each American coast. He does not single out the Gulf shore this time around.

He’s also not taking a firm stand on whether El Niño will stay in place through the hurricane season.

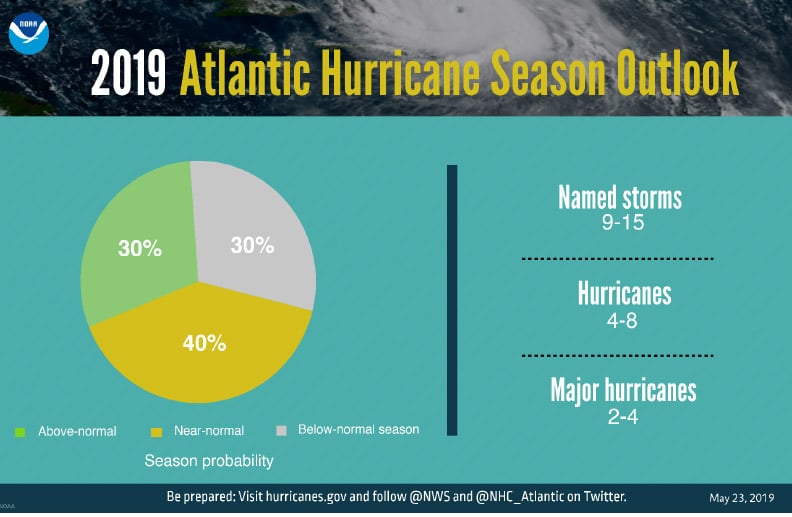

NOAA (the U.S. Weather Service) has released its hurricane forecast for this year, and it is pretty closely in line with Kottlowski’s. NOAA is calling for four to eight hurricanes and a range of two to four hurricanes. NOAA calls this a “near normal” season. The agency seems to believe that El Niño will stay in place — good news for us.

The Weather Channel’s forecast for the 2019 hurricane season is a bit more pessimistic than Colorado State’s. The Weather Channel calls for a total of seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes (versus the five hurricanes and two major hurricanes predicted by Colorado state).

Of course, the fact that a hurricane (or any sort of storm) forms over the Atlantic does not mean that it will hit the U.S. coast. But the possibility is always there. This story concerns long-term forecasts that make no predictions about when or where or whether a hurricane will develop or land.

Short-term hurricane forecasts made after a tropical storm has formed and been named remain difficult. Meteorologists presently feel they can make a good prediction about landfall when a hurricane is still four days out. They are working to make this time period longer. Cities the size of Miami and Houston could certainly use more than four days’ warning if they are to evacuate.

Tools for both short- and long-term forecasts are only going to improve as the years go by. If this year’s long-term forecasts are close to accurate, there’s no need to be unduly worried. But every person in SWLA should be fully stocked on bottled water, candles, batteries and pork and beans all the same.

Comments are closed.