University of Lafayette Press, 2018, 152 pages, hardcover, $49.95

A Review By Brad Goins

Those who like big books that are filled with black and white photographs and have very little text will be gratified by Louisiana Trail Riders — a book just published by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press. Many of the photos spread out across two of the 9-inch by 12-inch glossy pages. The volume will be seen by most as a coffee table book; it may be too large to fit on the bedside table.

The story of the book began years ago when photographer Jeremiah Ariaz was riding his motorcycle on Highway 77 along Bayou Grosse Tete. When he saw a group of horse riders occupying the entirety of the road some ways ahead, Ariaz pulled over and began taking photos as he sat on his bike.

As the ride passed him, the last rider invited Ariaz to join the procession. He did so, eventually eating a great deal of jambalaya and doing a fair amount of socializing.

Thus began a five-year stretch during which Ariaz joined in with Louisiana trail rides and photographed what he saw. Ariaz says the experience changed his long-held notions that a cowboy was a person who was “gruff, serious, white and situated in the West.”

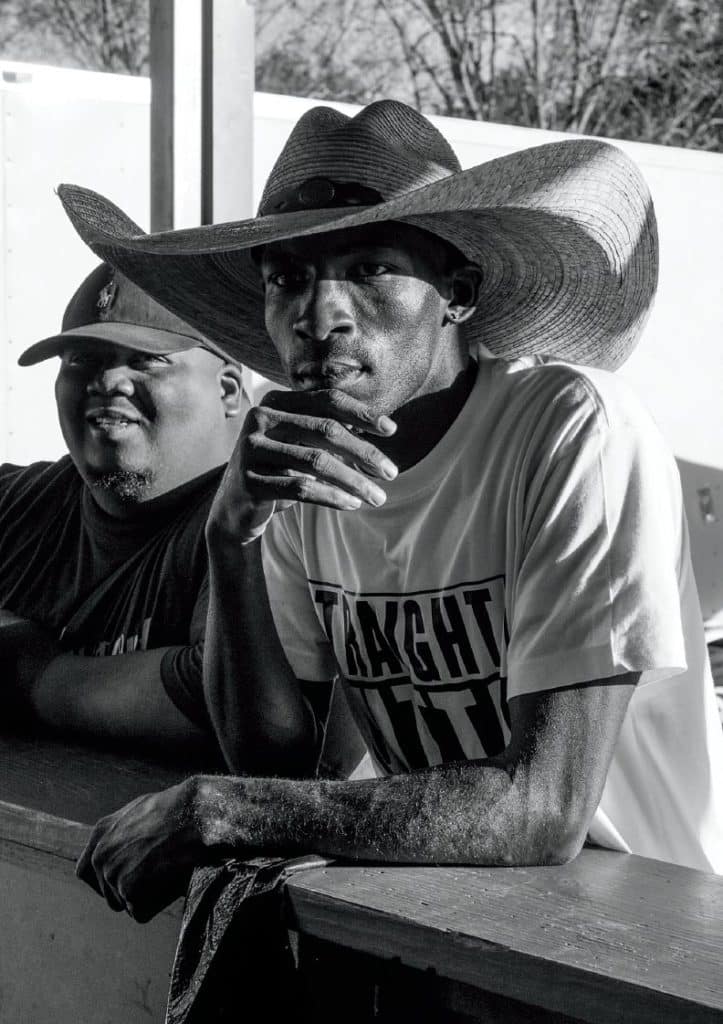

Ariaz’ photographs are testimony to all sorts of fashion statements, including a gigantic belt buckle in the shape of the state of Louisiana. One fellow wears what might be a fishing cap, with tags and loops of paper hanging down from it. In one shot, a pensive male stares intently at the horses from under a sombrero. He sports a STRAIGHT OUTTA COMPTON t-shirt.

Throughout the book, fashions are simple and casual, perhaps reflecting the current emphasis on “street style” in its myriad forms. Although there is some western wear, it’s practical; not elaborate.

There are photos of DJs of various ages working with mix boards as they ride in the beds of trucks or in trailers. (Ariaz asserts that music is continuous during trail rides.)

An All-Ages Show

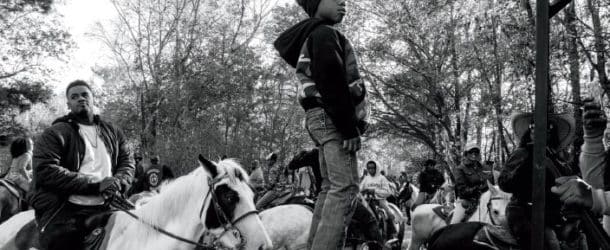

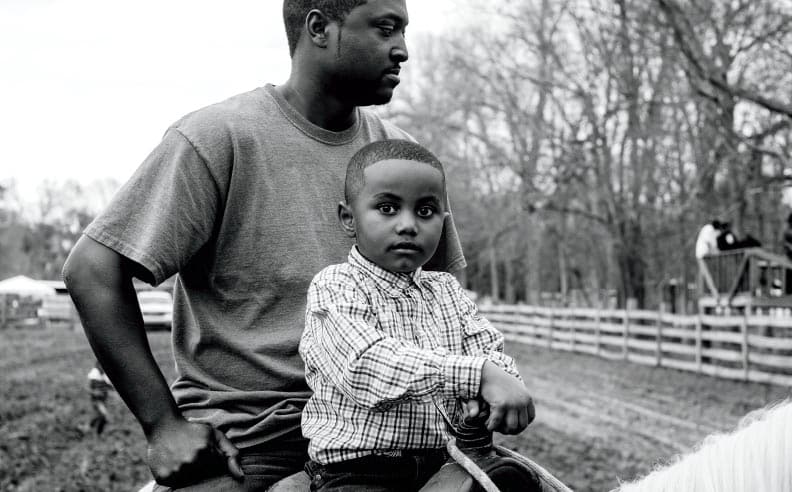

Many children who appear to be 12 or younger ride horses. In one shot, a youth stands confidently on top of a saddle on a horse. In another, one who’s still young enough to suck on a pacifier naps in a cart drawn by a horse. Young as he is, he’s already wearing cowboy boots.

Trail ride participants range across genders and age groups. One photograph shows a group of mothers in lawn chairs watching riders saddle up. One gets the feeling that the rides are family affairs, with those of all ages attending.

There are half a dozen shots of a trail ride filling either one lane or the entirety of a road. In one shot, cars drive in one lane while the riders occupy another. It could be the cars are full of people viewing the riders as they move along.

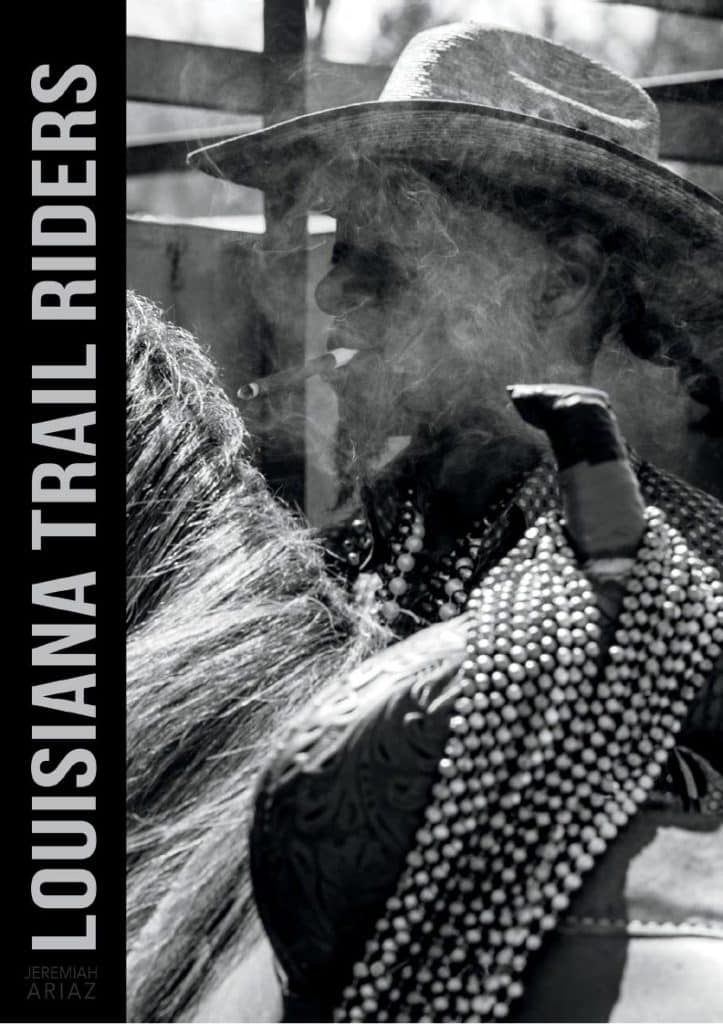

Ariaz likes to photograph riders as they appear in the reflections of truck windows. For the most part, his work falls firmly in realistic traditions of photography. It’s interesting to note, though, that the cover shot is one of a rider blowing so much smoke out of his cigar that his facial features are entirely covered. Even without the facial features, one can tell immediately that the figure is all cowboy.

Two pages of the book list the dozens of trail rider group names. My favorite group names are the I Hustle Hard Riders, Watch Ya Self Riders, Shuga Shack Riders, Gutta Girls Ridin Dirty and the Crazy Hat Riders.

Cowboy Culture And Today’s Culture

The book has only five pages of text — three of them devoted to the essay “Louisiana’s Black Trail Riders: A Living History” by Alexandra Giancarlo, a geographer and LSU graduate.

Giancarlo, who asserts that some of the first cattlemen in the U.S. were black, says the rides are seen as carrying on a long tradition. The tradition probably goes back at least as far as 1770, when, Giancarlo says, the New Orleans government gave away large tracts of land to anyone who could prove he owned 100 head of cattle and two slaves to attend them. Some wealthy ranchers used this opportunity to give their mixed-race slave sons the chance to establish their own ranches.

As the photographs in the book attest, the trail riders make strong references to the traditions of cowboys and ranchers. Riders take pride in their horse ownership and their cowboy ancestry. But trail rides now have no connection to cattle. The present-day culture of the riders is greatly in evidence. Today’s rides are usually complemented by cookouts, campouts and zydeco performances.

Rides are proceeded by a communal serving of “Cowboy Stew,” made of mixed meats, Creole gravy and rice. For the break in the middle of the long ride, pork steak sandwiches are the food of choice.

Trail riders tend to be rural, Creole and Catholic. Today’s rides are most common in Southwest Louisiana and East Texas.

The riding groups function under the auspices of a few major riding associations. Each association has one large annual ride. Some of these rides are big enough to attract out-of-state vendors. The annual Step-N-Strut ride, which draws an audience of thousands, may look more like a festival than a horse ride to some.

Giancarlo says the present format of trail rides developed 30 years ago. It seems to be always evolving. Although the events involved with a ride will fill several days, the one long trail ride takes place in a single day. Multi-day rides are going out of style.

Culture scholar Dustin Cravins says that social trail rides developed in the eras when horses were the primary means of transportation. He says, “it was … something to do in the middle of nowhere.”

‘I’ve Got To Stay Out Of Trouble’

Although Giancarlo says female trail riders are still relatively rare, I felt as if I saw photos of plenty of them in this book. Some riders say that duties are now divided equally between men and women. But Giancarlo asserts that the person who carries the flag for an association “is usually a male.”

Rural participants are gradually bringing hiphop culture and music into the rides. The feeling is that it’s acceptable to embrace contemporary black urban culture as long as one remains true to the traditions of the cowboy.

Many feel that the trail rides keep young people from getting into trouble. Acynthia Villery, president of The Bill Picket Trail Riders, says she’s had young people tell her, “if it wasn’t for this [trail riding] life, there is no telling where I’d be. So now I have a responsibility. If I want to ride, I gotta stay out of trouble. I have to take care of my horse.”

To learn more, visit louisianatrailriders.com or ULPRESS.org or call (337) 482-6027.

Comments are closed.