A New Children’s Book Is Part Of His Effort To Keep Cajun Culture Alive

Story By Justin Morris • Photos By David Simpson

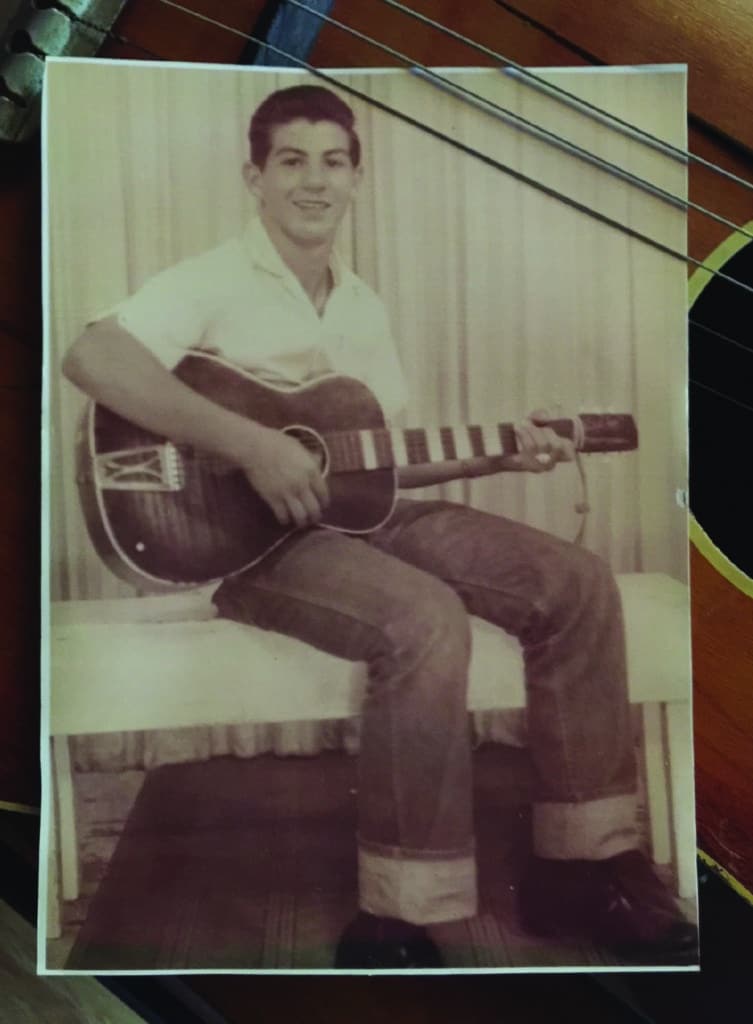

It’s hard to imagine 65 years of major label recording contracts, international tours, Grammy Awards, Billboard Top 10 hits, collaborations with musical legends, and more stories than you can shake a “baton” at. But I know one man who’s not only had all those things but has maintained the same passion for them he had when he first started so many decades ago. That man is Jo-El Sonnier.

For those not aware of the living legend, Sonnier hit the country charts in the very late ‘80s, and gave us two Top 10 hits (“No More One More Time” at No. 6 and the Richard Thompson-penned “Tear Stained Letter” at No. 8.

He truly brought the Cajun diatonic accordion to the mainstream charts for the first time.

After all the international success this Cajun boy from Rayne, La., has known in his half century of playing and performing, does he find himself in L.A., Nashville or New York? Naw, sha. He’s right here in Southwest Louisiana. And despite his recent lack of chart appearances, he’s working harder than ever, with a focus far beyond making records and winning Grammys.

Jo-El is trying to change the world.

Am I talking some great political change? No. Social change? No. Some great cultural change? Well, maybe … I can say that the change he wants to see is in the lives of young children.

Southwest Louisiana’s claim to Country Billboard fame has somehow found his way from the stage to the pages of a couple of children’s books just starting to make their way into the world. Although our local living legend just graced the legendary Opry stage at Nashville’s historic Ryman Theater a few weeks ago (more on that later), he has something much more pressing on his mind: spreading the word about the book The Little Boy Under The Wagon.

Who is that boy? Well it’s Jo-El, actually. The new children’s book penned by his sister-in-law, Shirley Strange-Allen, not only tells an anecdotal tale of his childhood, but also addresses pertinent and complex issues facing many young children.

I was fortunate enough to sit down with my longtime friend and his sister-in-law to find out a bit more about the method, meaning and message of The Little Boy Under The Wagon.

Shirley Strange-Allen: It actually began when we found out that Jo-El was going to be teaching a class at Lamar College. We started trying to put together his personal history. I said to start from the very beginning, and that’s how it came out. [He said,] “Well, we went to the cotton fields, and I was little and couldn’t pick cotton, so Momma put me under the wagon, to keep me out of the way and keep me safe. But I kept crawling off!”

So eventually, they got an accordion from someone and put it in his hands. And that’s what kept him occupied under the wagon so he wouldn’t wander off.

Then he started telling me his stories about how he grew up — even his first trip to the chicken fights, where he went to play his accordion and earn money. They’d throw coins to him between the fights, and he’d gather up the coins. of the class. So no one really knew what he went through.

Before he went to school, he got up to pick cotton. Then he went to the radio station and played. And then he got to school. At 13, he recorded his first record. [He] didn’t realize that he had to have something for the flip side. So, he went out to the truck and sat there and wrote a song that became a big French hit.

Jo-El Sonnier: “Tes Yeux Blue,” that’s right. I went to record with the Duson Playboys Special, which was the band — Jo-El Sonnier and the Duson Playboys.

We recorded with Floyd Soileau in Ville Platte. But the problem was when we were done recording the song and started packing up the gear, Mr. Floyd called us back and asked why we were packing up. I’m talking to him in a heavy accent and in French. And he says “You can’t leave” and I asked him, “pourquoi pas?” and he said that we had to have a second song.

We didn’t know anything about making records. I had what my mother told me before I left the house, which was about this song “Tes Yeux Noir,” “Little Black Eyes,” by Lawrence Walker. She told me if I was going to make a record, I should do a song about tes yeux blue — the little blue eyes. So I thought about that along the long drive to Ville Platte. This little melody kept ringing in my head. So when Mr. Floyd said we needed a second song, that was it … The band just jumped right on it, even though we were all beginners … steel player, drummer and everybody else.

Shirley: And it became just a huge French song. That day when he got home from recording the record, [he found that] she had taken old pie pans and nailed them up on the wall by his bed. She told him that one day they would all be gold records.

Jo-El: She was an amazing little person and very supportive of my music. She didn’t go to many of the places I played dances at. She didn’t believe too much of that, you know. So, she stayed home a lot. But when she went out, she was a lot of fun.

Now, daddy was a dancer. My God … everyone wanted to dance with my father.

But you know, he was a sharecropper, and that really was his first love. I saw it was hard working out in the field. As I got older and understood more about the economy and the ways of making a living, I just thought that maybe if I went out and played in clubs that I could make a little money to help my family out. Back in those days $10 was a big deal. So, I even got to where I was carrying my records around on my bicycle and selling them. Not only that, but I did inspire a lot of people to buy phonographs, which were pretty expensive at the time. But it was something a little special for the poor folks who liked the music. So, I would tell them that the only way they could hear this little record was to get a phonograph. I’d ride my bicycle with my little box of 45s. [By this time], it wasn’t the “Tes Yeux Bleu” I was selling; these were other records I had done at Goldband Records in Lake Charles … Sharing the music and letting everybody know that I was making records … was how I started my journey.

Justin: So, when did you start recording with Eddie Schuler?

Jo-El: That was around ‘66, so I was about 20 or so. I recorded several albums with him after doing several with Mr. Floyd. [I did] some with Fais-Do-Do Records out of Crowley, where I did a record for my mom called “The Mother’s Day Waltz.” The flip side was a song called “Memphis.” I did a little different arrangement with the accordion at the time, so I was starting to incorporate a progressive sound. But the waltz was a hit, and it just started progressing. I kept finding ways to get on stage and share my music and the music that I heard coming up — George Jones, Hank Williams, Sr., or people like Ray Price. I’d write those songs in my notebook. Before long, I was singing songs in English. But that’s really how it all started for me 55 or 57 years ago.

Justin: That’s an interesting point, though — in those days, it really was all about self-promotion and that was really all you could do was find ways to get your message out, which … was “Well, I have a record. Listen to my record.” Now … after all these years … you still have that same fundamental sensibility about you in that you’re finding new and independent ways to get that message out … A shining example of that is … this book The Little Boy Under The Wagon. But now that message is a bit different. Where it was “I have a record,” it’s now “I have a story.” A story, a life, a legacy and history. This question is to both of you: why do you think a children’s book was the medium to share this message?

Shirley: We’ve been talking about the fact that it seems we have a generation that have kinda lost the Cajun heritage, and it’s not like that was all necessarily by choice. Children were eventually forced to speak English in schools. It became cool to not be labeled as a Cajun performer. Now, they’ve finally been bringing French back into schools, which is wonderful because we were becoming so homogeneous that we’ve forgotten who we even are.

So, inside the book it says from “Bayou Boy to Living Legend.” His story starts as a young boy on the bayou or in the cotton fields. And it wasn’t something that someone grabbed him up and started pushing him and promoting him and making a smooth path for him. He did it all by himself. He had a lot of good hands to help him up: my sister, for one, who for the last 25 years has helped him all along the way …

[How many people] can say they were good friends with Johnny Cash? I only know one. (Laughs). He’s written songs that have been recorded by The Flying Burrito Brothers, Emmy Lou Harris, John Anderson, Patty Loveless … He even told me a story about a Jerry Lee Lewis record that was coming out and they didn’t know who had written the song. They called Jo-El to see if he knew or could find out who wrote it. Sure enough, it was one of Jo-El’s.

Justin: What song was that?

Jo-El: “One of Those Things We All Go Through.” I wrote that with Bucky Lindsey. But you know, my all-star cast band included Sneaky Pete, who played with the Burrito Brothers; Garth Hudson from The Band; Albert Lee, who played with the Everly Brothers; and many other great acts. And the list just went on. We had so many guys that it was kind of interchangeable and we could do different line-ups …

Shirley: I taught gifted children for 30 years, and some of those gifted children were very much like Jo-El. They were very withdrawn and quiet and very shy … Some were even non-verbal. But they had such talent that all it took was someone to help pull that out. As a teacher, you see that and you want to help them along to be more confident and tell their stories …

That first time Jo-El and I discussed this [book], we stayed up until 3 in the morning. I just had flashbacks to these other young men I had in middle school. And I always said that I needed to tell their stories. So instead, I’ll tell Jo-El’s story. And in the back of the book, it tells their stories as well: how they went from the shy, quiet little boys to what they became. One, we didn’t think he was ever going to speak as far along as sixth grade. [Now] he’s published three novels. The other was picked on for his poor clothes and his ratty jacket that he would stuff everything he owned into practically and wear … every single day, year-round. He now makes handmade guitars, and has made them for Eric Clapton and Mick Jagger …

Jo-El was fortunate enough to have someone to keep encouraging him. There’s a portion at the back of the book for adults and educators to read about children that are different, and how we need to encourage them and keep them going and interested and motivated in what they’re doing; and the fact that it is OK for them to be different, and sometimes it’s the most important thing there is. We had a lady tell us yesterday that as a left-handed child, her teacher tied her arm behind her back so she would write “normal.” And she sent us the sweetest note about the book thanking us because [we said] it really is OK to be different. It’s not something that we have to change to make you fit this normal mold. That’s such a disservice to so many children.

Justin (to Jo-El): And do you feel that that was important to you, that being allowed to be different?

Jo-El: Well, my “old faithful” was my accordion and the support of my family and my musician friends. You’ve got to remember that most of the musicians were older than me and more seasoned, and they still took to my music and supported what I was doing. Even those big names I played with … were willing to be side musicians to play with me and play my music. Johnny Cash brought me in to play on his record; and Merle Haggard, Alan Jackson, then Dolly Parton (“Why’d You Come in Here Lookin’ Like That?”), Hank Williams, Jr. And he was very gracious. He invited me to play on his recording of “Norwegian Wood,” the Beatles song, and it was the first time he’d ever heard a Cajun accordion … They originally wanted me to play a concertina and I didn’t even know what that was. (Laughs.) But they let me bring my Cajun accordion and he really liked it …

Things like that did make a big difference. They allowed me to keep my roots and share my roots, and that was so important.

JM: And this book is out now?

SSA: Yes, it came out [Nov. 9] The best way to get a copy is … via Jo-El’s Facebook page.

JM: And not only is this one already available, but you said you have another one due out in a couple of weeks.

SSA: The other book is There’s A Mouse in My Accordion. It’s kind of like the rest of the story. One of the first things we discussed about this book was [Jo-El’s] first accordion. He told me the first one he could remember was the one he kept under his bed, which was actually his brother’s. He remembered once pulling it out and having found that a mouse had chewed its way into the bellows, and he used chewing gum to patch it up. So, after hearing this, I got to thinking, “what if that mouse had stayed in his accordion?” And it just kind of developed from there.

Having taught many special needs children over the years, I decided to make this mouse deaf. His mother had brought him in the house to keep him safe and stashed him away in the big black box under the bed. So, Jo-EL finds him, and as he learns to play the accordion over the years and gets better, the mouse begins to “hear” the music from the vibrations through his feet. As Jo-El’s story progresses, so does the mouse’s. He travels all over the world with Jo-El.

We decided to place [Jo-El] and “Marcel” in big historical moments. Jo-El loved Mickey Mantle. So, we have Jo-El and Marcel set up to play after the game when he hits his 500th home run … And [there are] other heroes, Martin Luther King, Kennedy (whom he actually met at The Crowley Rice Festival in 1959 mere hours before his winning the Democratic Nomination for President), Elvis … In Europe, we had the Queen; we had the Pope at the Vatican; the first moon landing …

We even bring it up to current day. At the end of the book, it’s mentioned that Jo-El was at the Ryman Theater playing the Opry, and that he just had a children’s book come out (The Little Boy Under The Wagon). Marcel notes he wasn’t mentioned one time in that book, so he figured he’d write his own. (Laughs.)

[The new book] has references to Cher and when he worked with her on “Mask”; and his other movies; pictures from when he was on Hee Haw; wedding pictures and other personal photos.

It’s another book about not letting your limitations or disability or whatever makes you different keep you from living and dreaming. The little mouse may have been born deaf, but the music allowed him to “hear” and go experience everything Jo-El did.

JM: Fantastic … (To Jo-El) I haven’t seen you since [you were on the Opry] and I’ve been wanting to ask about that. So, you have played for the Opry before, haven’t you?

Jo-El: Well, I’ve played at the Gaylord Opry (in Branson) several times. But this was the first time I’ve played the Opry House — The Grand Ole Opry — at the Ryman. We sold out both shows. I was there with Ricky Scaggs, The Whites, the great Bill Anderson, and Connie Smith, whom I love dearly. She is a wonderful lady and sings like a bird. Man, it was very nice and very special. So, I went up there and I did my tribute to people like Hank Williams, Sr. I thought about George Jones and Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash and Jimmy C. Newman. We all had something in common, and that is a love for Cajun music.

We did one of the first songs I ever played when I started translating and trying to perform English music; and that was “Jambalaya.” I remember Happy Fats Leblanc with a group called the Rainbow Ramblers from Rayne. They started way back in the swing and Cajun days. I remember him coming to my house. He was nice enough to do the translation of “Jambalaya” in French. I didn’t want to let him down, so I started singing it in French. It’s those types of things that inspire me to continue with my roots; do my French music and “Jambalaya” and other material. But that’s how I carry myself as a performer. So, when I had the opportunity to do the Grand Ole Opry, I was touched very deeply by that.

JM: So, how did that come up?

Jo-El: Well, we were going to Nashville to do some work with John Schneider (of Dukes of Hazard), who called me up and invited me to town while they were working on a video and recording some music. He asked me to bring my accordion, so I knew something was up so I brought all [my accordions] with me. I went to the studio to record on a couple of songs for John. A really cool thing was I got to play on one of those with the great Mac Davis. It was such an honor to play with someone like him on a song he wrote.

It turns out that while we were there working, it was the 37th anniversary, I believe, of “Just a Good Old Boy,” which Waylon did for the Dukes of Hazard. They had just recorded a new version with the Hot Nashville Pickers. So, a bunch of people were in town, including one of the stars of the TV show, and the song was getting played around town as everyone celebrated [it] …

The Opry was just wonderful. I dedicated the evening to my parents from the stage because they had that vision for me long ago and said that one day I’d do the Grand Ole Opry. So, I said to Mom and Dad that that was our night together up there on the Opry stage. And there’s only one Opry. So, it really is the “mother church” for that type of music. They’re very much like a family. So, to allow us to come in and be a part of that was a real blessing.

JM: So, what do Jo-El fans have to look forward to?

Jo-El: I get asked that a lot. We just keep going. It might be different music out there today, but we still keep on. That’s part of just keeping the music alive. It doesn’t mean you have to change what you do. I proved that when I brought my Cajun accordion into that studio with all those great country artists and did my part. You just had to be prepared and stay focused, and when you have that opportunity to do something, be thankful and grateful and know that someone up there is looking at ya.

When I get on that stage now, I don’t carry the instrument by myself anymore. I’ve lost so many heroes in Cajun and country music and in my own family. So, that’s why I try to carry that banner. The music lifts me up and brings those heroes back to me and brings fans and friends who remember me, even from [when I was] playing on the radio at 6 years old. I’ve had great fans all along that have backed me up and helped me to keep pushing that envelope. When I won that Grammy, I knew that there was still a place for us and our roots and we should be proud of that. Many people before me never had that chance, so I carry that torch for those people, as well.

We’ve lost so many artists through the years, but they are not forgotten. Not on my stage. They’re all there in spirit. I’m just grateful that they are still with me.

If you get a chance to be around someone that speaks French, take the time to learn it and speak it with them. The French world, that Cajun world, is a unique culture, and that’s why I’m identified with what I do. It’s part of our life, and we need to cherish and embrace that … ‘cause when it’s gone, it’s gone.

Well, rest assured, the tenacious King of the Cajun Accordion is anything but gone. Now, at 71, Sonnier continues to wave the banner for all things Cajun and continues to play shows locally, domestically and abroad. He is now focusing on sharing the story of his life, his music and the Cajun culture while encouraging challenged young children to overcome adversity and strive to do great and wonderful things.

I remember that when I was a young child in Dallas, my father pointed out the dark-haired man playing an accordion on CMT and told me that that was Jo-El Sonnier and from Lake Charles. Even at that age, I found inspiration in knowing that if that Louisiana boy could be successful enough to have a video on CMT, then maybe one day I could, too. While, clearly, that hasn’t been the case, I have been fortunate enough to get to know the man behind the music. And while the talent, career, success and legendary friends he’s had over the years are impressive, they pale in comparison to the heart, passion, drive and spirit he has for his culture and home.

The Little Boy Under The Wagon and There’s a Mouse in My Accordion are available through Jo-El’s Facebook page: facebook.com/comeonjoe. Also, be on the lookout for a children’s record featuring songs from an earlier children’s album he’s recorded, and some new content inspired by two books expected sometime next year.

Comments are closed.