The Rougarou And Other Fearful Creatures That Haunt The Bayou

By Brad Goins

Cryptozoology is the study of imaginary or mythical creatures. American historian Robert Damon Schneck, who emphasizes that cryptozoologists endeavor to take a scientific approach to their subjects, breaks down cryptids — the creatures studied by cryptozoologists — into three types:

1. “Creatures that might exist” (for instance, the Loch Ness Monster).

2. “Familiar species that appear outside their normal ranges” (for instance, we step outside and see a kangaroo).

3. Creatures “which have been declared extinct, but could still survive.”

Schneck states that in the United States, the cryptid most sighted is one that can be called Sasquatch or Bigfoot. This gives us a smooth transition, as Sasquatch and Bigfoot legends are common in the rural areas of Southwest Louisiana.

The similarity these Sasquatch share with human beings enables them to qualify as imaginary creatures or cryptids. Cryptids must, in some fundamental ways, resemble biological creatures with which we’re familiar. Ghosts or spirits wouldn’t qualify as subjects of cryptozoology. They aren’t three-dimensional beings.

If a Sasquatch existed, I would, I assume, be able to reach out and touch it or feel it if I were able to and inclined to. The same would apply to such imaginary creatures as werewolves, chupacabras, yetis and so forth.

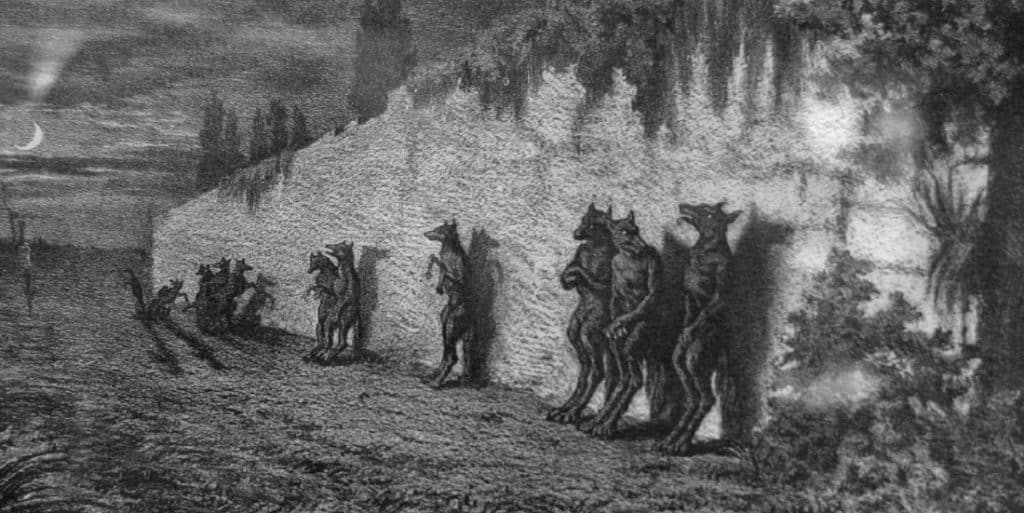

Rougarou or Loup Garou

Since the appearance of the first Twilight movie in 2009, the werewolf has been a cryptid that’s played a huge role in American popular culture. Its influence has, I gather, spread far beyond the Twilight movies into other movies and TV shows.

Although I’ve never seen a Twilight movie, and will, I assume, never see one, I believe the werewolves of Twilight have some things in common with the werewolves that play a prominent part in the folklore of Southwest Louisiana.

This werewolf is called either “Loup Garou” — the Parisian French term for “werewolf” — or the variant term “Rougarou.” The experts agree that in Southwest Louisiana, the two terms are used interchangeably.

In general, in South Louisiana folklore, the Rougarou is usually a resident of a town who appears perfectly normal during the day. But during the night, he takes on the appearance of a wolf or some other animal.

In some stories, the Rougarou keeps his human figure but has the head of the wolf.

At the time when French Acadians and French Gypsies began to inhabit the Southern Louisiana swamps in large numbers, wolves were rarely seen in the area. As a result, the werewolf stories these groups brought with them altered, and the Rougarou was often said to change into something other than a wolf — for example, a dog, pig, cow or chicken — come nightfall.

Because the Rougarou is often colored white in the oral narratives about it, it’s of interest that south Louisiana artist George Rodrigue made his famous rendition of a Rougarou blue; I’m referring, of course, to the famous “blue dog.”

Yes, the Blue Dog of George Rodrigue is none other than the Rougarou itself; Rodrigue initially painted the dog as sitting in cemeteries, on the grounds of abandoned mansions and in other eerie settings. As sales of the paintings grew, the Blue Dog started showing up with brightly colored, cheerful backgrounds. Eventually, all that remained of his sinister beginning was his slightly melancholy expression.

The Basic Story

The most fundamental Rougarou story goes something like this: the person-turned-animal does something to provoke a pedestrian who’s out at night. (In some parts of South Louisiana, the word “Rougarouing” means going out or hanging out at night.) After being provoked, the pedestrian eventually becomes frustrated and attacks the creature, drawing three drops of blood.

After the drawing of blood, the Rougarou returns to its human form and tells the attacker its name. The attacker is told he must keep the story of this encounter secret for a year and a day (or in some versions, 101 days). If he tells a soul during that time, he will become a Rougarou himself.

In some versions of the story, the attacker who doesn’t observe the one-year limit commits suicide.

Who’s to say whether anyone in South Louisiana has killed himself because he really believed he’d drawn the blood of a Rougarou? If someone did so in years gone by, he might have fallen victim to the same kind of group psychology that is said to lead to the demise of an individual who’s been cursed by a witch doctor.

In some variants of the story, the Rougarou is said to punish his victims not for attacking him, but because they have failed to keep a resolution they made for Lent. There is an old French folklore tradition in which an individual who violates the rules of Lent for seven consecutive years turns into a werewolf.

A Kinder, Gentler Werewolf

There are more benign forms of the Rougarou story in South Louisiana culture. Often the figure is a vague one who’s mentioned to keep children in line. Over time, some rural elders have told children who misbehave that “the Rougarou’s going to get you.”

It was this type of Rougarou/Loup garou that served as the inspiration for Rodrigue’s Blue Dog.

Rodrigue states: “My mother told me this story growing up [in New Iberia], that if I wasn’t good, the Loup Garou would eat me up at night … The dog, she never moves.”

Like the color blue, the notion of a stationary Rougarou seems to be an unusual variation on more common Rougarou tales.

The Werewolf of Many Names

The term “Rougarou” was widely used among the Cajuns, French Gypsies (the “Mamouche”) and other groups who settled in the Atchafalaya Swamps.

French Acadians living in Canada picked up the term “rugaru” when they heard it used to described the Wendigo cryptid that was said to live in the area. The Wendigos had some similarities with werewolves. They were humanoid creatures who were the size of giants; sometimes they were said to be human beings who had been possessed by evil spirits.

Wendigos appeared to live in a state of perpetual starvation. Their ribs could be seen through their skin. They were covered with sores.

Wendigos were thought to engage in behaviors that were taboo. Thus, they might engage in murder, excessive greed, cannibalism and so forth. Today, a patient who has been diagnosed as having a “Wendigo psychosis” is an individual who both wants to be a cannibal and fears he may become one.

The term “rurgaru” came from the Michis language that was spoken by the Metis people of Canada. Metis were descendants of Obijwe, Cree or other first nations people and French or Scottish Canadians.

The Michis language or dialect is spoken not just in Canada, but also in North Dakota, where the Obijwe have a strong sasquatch tradition in their folklore.

For the French gypsies, the rugaru creature may have seemed closer than Loup garou to the “strigoi” wolfman they’d learned about when they lived in lower Eastern Europe. The strigoi wolfman that was well-known in Romania was definitely a malevolent creature that endeavored to drink the blood of human beings.

Native Americans living in or near the Atchafalaya had their own “Wendigo” and “Sasquatch” traditions. The werewolf of the Attakapas tribe was especially feared as it was thought that the creature could eat human beings. That’s an obvious similarity to the Wendigo that the French Acadians would have been familiar with.

In contrast, the sasquatch that is sometimes talked about by the Opelousas tribe is said to pose little threat and tries to avoid people. As far as I know, it’s a universal feature of films made of Sasquatch or Bigfoot in North America that the creatures are always shown lumbering off in the distance; they are never seen making an effort to attack the cameraman.

At any rate, the idea that some sort of humanoid creature with wolf-like or bear-like features is wandering in the swamps or woods of South Louisiana is a well-established one.

Early Wolfman

Perhaps the explanation for the werewolf in our neck of the woods is the simple one that there just has to be something frightening in swamps so large, dark, meandering and eerie in appearance. The presence of fear in a place of myriad forms hearkens back to the origins of the wolfman thousands of years ago in Europe.

At the time, the werewolf was not a fearsome creature who came out at night when the moon was full. Originally, a werewolf might be found anywhere darkness lingered — under a bush, under a bed, in the shadow of an abandoned building. The werewolf symbolized the idea that frightening situations can arise anywhere given the right circumstances.

This symbol of everyday frights was originally far less scary than the Rougarou. The first werewolves Europeans thought they had glimpsed were probably ordinary men or shaman or priest figures who donned wolf pelts for rituals or the ceremonies of Dionysius. Once these early figures removed the wolf pelt, they removed with it the symbolism of threat.

As the werewolf legend took on more layers down through the centuries, the European werewolf became much like the “shapeshifter” or “skinwalker” that Native Americans told European settlers about. In the period of European settlement of North America, both the Native American and European werewolf figures changed from man to wolf and back to man.

In the Europe of that age, to change from one form to another was thought to be contrary to God’s will — hence the werewolf’s reputation as an unusually evil creature.

And that brings us, with a bit of a jump, to the werewolves of Hollywood culture. The evil werewolves depicted in Medieval European woodcuts are immense, hairy, ferocious creatures who look a great deal like the monsters in both of the American Werewolf in London movies.

The Move To Crytozoology

Rougarou still has some status in the folklife of the state. Houma still holds its Rougarou Festival. An online literary journal at UL-Lafayette is called Rougarou. And a life-sized statue of a Rougarou is on display at the Audubon Zoo in New Orleans.

Far and away, the most frequent mention of Loup garous and Rougarous takes place in fictional books, movies and TV shows. However, there are some strong signs that the stories of these imaginary creatures are moving from the realm of popular folklore to that of cryptozoology. An episode of the TV show Monsters and Mysteries in America has been devoted to the Rougarou. And the History Channel has run a TV series titled Cyptid: The Swamp Beast. In the History Channel series, the “Swamp Beast” in the title refers exclusively to creatures that have been sighted in South Louisiana.

Another passage reads, “one things [sic] for sure, if our name is brought up on the evening news, you need to pay attention, because we just solved the mystery.”

A more recent player on the scene is the Louisiana Bigfoot Organization, or LABO, which has been doing its work since 2012. One of the group’s mottos is “Which friend will save you from Rougarou?”

One of the imaginary creatures LABO researches is called Dog Man. On its Facebook page, LABO provides a number of links to YouTube videos of Dog Man sightings. These YouTube videos have such titles as “Dogman Caught On Tape” and the simple “The Dog Man!” (with an exclamation point).

The idea of Dog Man stories appearing on the group’s site isn’t a huge stretch. In his writings on American Sasquatch, Schneck says that in various legends, these tall, hairy, man-like creatures have transmogrified into “firey-eyed dogs and cats, wild horses … diabolical livestock” and even “a talking toad.” This is certainly comparable to our story of a Loup garou taking the form of a small blue dog.

The Gulf Coast Bigfoot Research Organization provides a lengthy statement from a man who claimed to have sighted sasquatch-type creatures in Calcasieu Parish. The unnamed driver was heading east on I-10 near the Sabine River Bridge at 6:25 am. He saw three people walking down a tree line 35-40 feet from the interstate. At first, he thought they were people in need of assistance. The closer he got to them, the more inclined he was to think they were vagrants who were “very unkempt.”

“My first impression was … they had really long scraggly hair on their heads, like hippies … I noticed they were not clothed … Instead, their bodies were covered in … long dark, dark brown [hair].”

They “appeared to be a family. The smaller one was walking between the … one who was the largest and in the rear of the group and the next tallest one, who was in the front …” The driver felt the lead figure was a mother who was leading the way and the figure in the rear was a father, who was making sure the child in the middle walked in a steady manner.

The driver said he was unable to see the faces of the creatures because of the angle at which they were walking.

He said the creatures had been walking near the “Sabine River Turnaround.” He believed the creatures he had seen were the ones he had heard discussed and called “bigfoot” in the area. “There have been reports of sounds, footprints and other bigfoot seen in this area all my life.”

As for Bigfoot stories in the larger region, Schneck makes it clear that legends develop about such creatures on a regular basis. He cites a “gorilla hunt” that took place in Ralston, Miss., in 1952; a group in Clanton, Ala., that chased an animal they called “Booger” that they said ate peaches; and the Lake Worth Monster in Texas, which attracted the attentions of “carloads of armed hunters” in 1969.

The Honey Island Swamp Monster

Even though the last cryptid I wish to mention was sighted on the other side of the state, it might be work looking at because of its similarity to the bigfoot talked of in this area. The monster in Honey Island Swamp 10 miles southeast of Slidell was first spotted by wildlife photographer Harlan Ford in 1963. Ford said the humanoid animal was 7 feet tall, covered with gray hair and had red eyes.

Ford gained a certain amount of national publicity in 1970 when he claimed to have found footprints showing that the monster had three webbed toes. (If you wish to see a plaster cast of this footprint, it can be found in the Abita Mystery House in Abita Springs.) When Ford died 10 years later, a Super 8 film of the monster walking through some woods was found in Ford’s possessions.

The Honey Island Swamp Monster has a certain status in popular culture. One of the dolls in Mattel’s Monster High line is named Honey Swamp. And a group of Hurricane Katrina refugees that united in San Francisco formed a blues band called The Honey Island Swamp Band. The band is still together and is touring the U.S. at present.

But far and away the most attention devoted to the Honey Island Swamp monster comes from popular television shows that at least make the pretense of doing serious investigations of cryptids. The programs include Fact or Fiction, Lost Tapes, In Search Of … and Monsters and Mysteries in America.

Diehard cryptozoologists will keep writing books and articles about the plaster casts of mysterious paw prints found in the Atchafalaya mud. Some of them will wear the Louisiana Bigfoot Hunter t-shirts that can be bought on Amazon.

Cryptozoologist or not, it might be a good idea to avoid Louisiana swamps illuminated only by the full moon. If you do stray into them, keep an eye out for the presence of a crow. The South Louisiana legend has it that if a crow can be seen, the Rougarou is not far away.

If you see no crow, and some strange-looking creature shows up and starts to pester you, resist the temptation to attack. Better to be annoyed than to become a Rougarou.

Editor’s note: This text was first presented at the May program of the Southwest Louisiana Genealogical Society (rootsweb.ancestry.com).

Comments are closed.