THE LIFE AND CAREER OF A SOUTHERN GENTLEMEN

STORY BY SCOTT E. RAYMOND

PHOTOS BY JASON CARROLL & SCOTT E. RAYMOND

For Victor “Vic” Theodore Stelly, the first memorable impressions were probably set in the small town of Zachary, shortly after he moved there from Carencro at the age of 4.

The son of Gordon Stelly, a petro-chemical operator, and Dot Stelly, a stay-at-home mom, Vic Stelly says, “They were just hard-working, middle-class people and we lived in a little middle-class community.”

Stelly’s maternal grandfather was the sheriff of West Feliciana Parish. “We idolized him,” Stelly says. “We thought whatever Pawpaw said was gospel because he was a big deal.

“Athletics was (our community’s) big thing. Athletics was probably the biggest factor in my early upbringing because everything (conversation-wise) was based on how the football team was doing; how the basketball team was doing. My coaches and my parents were my biggest influence.”

Stelly was an All-State football player at Zachary High School. Then he went to Northwestern in Natchitoches, where he majored in health and physical education and minored in math, which, he says, upped his value to an employer, because schools were always looking for math teachers.

He played football at Northwestern. That is where he met his wife, Terry. They married in his sophomore year in 1960.

After graduating from Northwestern, Stelly taught high school at Redemporist and Broadmoor high schools in Baton Rouge. During that time, he got an M.A. from LSU in 1965.

Stelly speaks fondly of his next career move at McNeese State University from 1970 to 1974 as an assistant coach with the Cowboys. “I coached four years and loved every minute of it. Our highlight at McNeese was being temporarily ranked No. 1 in the nation in 1971 — that was great!

“The No. 1 ranking was determined by sportswriters nationwide.

“And of all the (schools) to knock us out of the No. 1 ranking was Northwestern State — my school! We were playing at Northwestern on a stormy, rainy night, and they tied us 3-3. Well, we were so down in the dumps about tying, we came back to McNeese and unloaded the bus that night. There must have been 100 McNeese supporters out there in the rain at 2 in the morning. And (someone) said, ‘Guess what?’

“‘We know,’ we said. ‘We got tied and lost our Number 1 ranking.’

“‘Maybe not,’ they said, ‘Delaware got beat.’

“Well, it was true, but even though they got beat, (the sportswriters) still ranked them No. 1; so at the end of the year, we were dropped to No. 2, with only that tie hurting us. It still wasn’t too bad. That was probably a highlight of our McNeese time.”

Following his coaching stint at McNeese, in 1974, Stelly began a successful 25-year career as an insurance agent with his own agency in Moss Bluff.

Political Beginnings And The Stelly Plan

Vic Stelly’s entrance into politics began shortly after a tragic 1981 event — when Sam Houston High School in Moss Bluff burned down. “Reapportionment had happened, and Moss Bluff was going to be able to have their first school board member,” Stelly says. “Somebody had to take the bull by the horns to rebuild Sam Houston (High School) … this was the beginning of (my political career).

“‘We want you to be the school board member (people said).’ (I) ran and won in 1983. At that time, we were trying to decide whether we were going to rebuild the school because it would take a huge tax increase. We had to pass a property tax — 96 mills. It is the most mills in the history (of the area). We passed (the tax), built the (high) school, built the elementary school at Gillis, and four years later, I felt like we had everything under control and I rode off into the sunset!

“When I didn’t run for reelection on the school board, I felt like I had done what the people had asked me to do: to get our school in good shape, and that was fine. At that point, I really didn’t anticipate going to Baton Rouge at all. But people started contacting me (about running for the Louisiana House of Representatives). We ran and we won and the next 16 years were in Baton Rouge.”

Stelly says that overall he enjoyed the experience as a member of the House of Representatives at the Capitol in Baton Rouge. “But one thing I did not like about the experience — and it’s getting worse — was the partisanship. I kind of got discouraged with the political partisanship. That was the biggest negative of the time I was in Baton Rouge, and it’s worse today than it was then. It is really bad today.

“Because of the fact that John Bel Edwards was elected governor as a Democrat, some people would say that’s not a big deal anymore. It is a big deal. He was the right man at the right time. John Bel had some good baggage — West Point (United States Military Academy) graduate … family in law enforcement. He was the right man, and I supported him.”

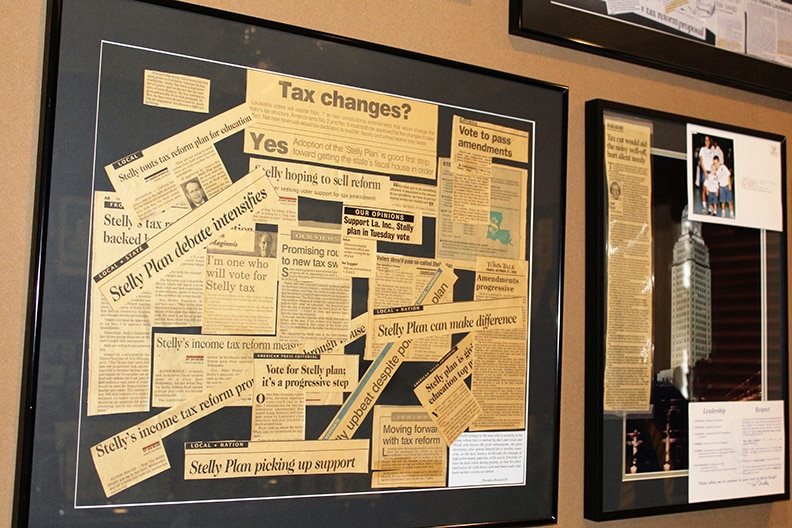

My conversation with Vic Stelly shifts to the historic 2002 constitutional amendment that had a major impact in righting Louisiana’s fiscal woes — the Stelly Plan. Says Stelly, “The main intent (of the Stelly Plan) was to get rid of the sales tax on food and also drugs — prescription drugs — and utilities, those three necessities of life. (The legislature) was taxing all three of those, and we had been taxing them on a one-year basis — a temporary basis — for 16 straight years.

“The first year, we were a little light on money. ‘Let’s suspend the exemption on food and drugs and utilities.’ Almost every state in America exempts sales tax on food, drugs and utilities because those are considered the necessities of life and adversely affect the poorest of our citizens. From a political standpoint and a leadership standpoint, passing a one-year tax and renewing it 16 straight years was ‘a pitiful way to run a railroad,’ according to (then Governor) Mike Foster.

“The first time, we suspended the exemption. A year later, we found out that we were still not any better off. We did this 16 straight times.

“Now, to suspend an exemption on taxes is just like raising a new tax. It takes a two-thirds vote of the Legislature to do that, every year for 16 straight years. So when we sat down with (Foster), he said we couldn’t continue doing this.”

Stelly says that discussions focused on how to compensate for the loss of several hundred million dollars after keeping the exemptions on food, prescription drugs and utilities. Finally, the conversation honed in on income tax.

“We have no state property tax,” says Stelly. “Everybody thinks you do, but that’s local. That’s all local services. Not one penny of property taxes goes to Baton Rouge, so forget about that.

“What’s the only other alternative you have? Income tax. Income tax is way more progressive than sales tax. It will grow faster than sales tax will. We need something that will grow because expenses grow. (Some) people don’t understand that there is inflation in government, so if we have a tax system that does not inflate like sales tax — well, sales tax does a little bit — income tax, over the years, will grow. You make more; you pay more.

“‘So, what are we going to do about income tax?’ (the question was asked).”

Stelly says he spent an entire year looking at the income tax alternative to sales tax and studying ways to come up with the right plan.

“We started studying. We studied for a whole year, comparing other states … what do they do? What do we do different than other states? We get certain exemptions; our brackets were different. We must have come up with 10 different plans.

“I get to the fiscal offices … By process of elimination, we ended up with the income tax adjustments that statistics showed in the Dept. of Revenue that 8 percent of the people in Louisiana would pay a little bit more in income tax. The rest of the people would benefit by it.

“Now, I was one of the 8 percent, and a lot of my constituents were also. But to their credit, a lot of them said if it would be better for the state, if it would balance our books, so be it. And it’s not unfair; we are doing the same thing other states are doing.

“We basically changed the brackets and came up with a combination of changing the brackets and taking away some exemptions that very few people used anyhow, and it came out basically revenue neutral, which is what we promised people.

“The people who didn’t like it were in the 8 percent. Of course, (they) didn’t like paying more. A few people paid more, but nothing like they thought they did. The movement was there; some legislators fought it.

“I made 122 presentations throughout the state on my own. In my car, I’d drive to Lockport; I’d drive to Shreveport. And I’d debate anybody there. Other legislators came and debated me; the President of the Senate, the Speaker of the House, they came and debated against me. We went around and explained it: ‘Some of this is going to go up; some is going to go down. But keep in mind, it’s not going to be revenue neutral forever because of the inflation factor. Income tax is going to go up a little bit over the years, but only when you make more.’

“So we sold it. We had to get a two-thirds vote of the legislature, which no one thought we could do. But once we got momentum going …

“When I made my speech on the floor of the House I said, ‘Fellas, there ain’t no Boudreaux (Plan), Thibodeaux (Plan) or Fontenot (Plan), there’s only the Stelly Plan. If you’ve got a better plan, let’s hear it, but right now this is the only plan.’ The thing of it is, they couldn’t argue because it was revenue neutral. They couldn’t argue that it was a pitiful way to run a railroad, like renewing a tax 16 straight years. They couldn’t argue the fact that we were wasting money. So when all the smoke cleared, we got our two-thirds vote.

“Some people were paying a little more income tax. You realize when you pay more income tax because you write a check for that. Sales tax: you don’t realize what you are saving.

“Some people were demagoguing things. It was easy to say the Stelly Plan was horrible. (But the truth is) it did work. No one was paying state sales tax on food, drugs and utilities.

“At the time, it was so maligned (by) people talking about it. One of my colleagues once asked in jest, ‘Did the Stelly Plan cause global warming?’”

The Stelly Plan income tax provisions were eliminated in 2009 by vote of the state legislature. When I ask Stelly if he thinks the Stelly Plan may reappear considering the state’s present fiscal condition, he says, “Well, they would never call it the Stelly Plan if they brought it back.”

“I was gone,” he says. “I wasn’t there to try and defend it. My term had ended, so I was just back home minding my own business. It’s a combination of things, why it was repealed. I talked with local legislators, and they said (repealing it) was the worst thing we ever did.”

Vic Stelly retired from the House of Representatives after four terms in 2003. “I had had enough and by that time, the Stelly Plan had passed. I felt like that was kind of like a good exclamation point at the end of my 16 years. I was not term-limited. I had done my mission, and I felt like that was enough. Let somebody else take the bull by the horns.”

In 2007, Stelly was appointed to the Board of Regents by Gov. Kathleen Blanco. He resigned that position six months before his six-year term was over, citing his frustration with the deep budget cuts in higher education. “We were just getting kicked.”

The Upcoming Election

My visit with Vic Stelly, who is now a registered Independent, moves to the upcoming Nov. 8 election, and his general thoughts concerning the challenges the winners of the Louisiana congressional races will face in Washington, as well as his thoughts on the presidential race.

“I think the nation is in as much trouble as our state is on a fiscal basis. (Those newly elected to Congress) will be fighting for whatever dollars are available at the time.

“I’m very depressed about (who) is going to be (in the White House). It’s not going to be a very good situation from the Oval Office, whoever wins. I’m very depressed about both candidates. With over 300 million people in our country, we should have two better candidates.

“Judging from history, as far as Louisiana goes, it’s a red state … Chances are a Republican will be elected. If you think about it — a U.S. Senator — if you had to have one political job, U.S. Senator would be it. There are only 100 (U.S. senators) in the world. You have a six-year term — nobody else has a six-year term. You basically can raise all the money you can spend for re-election. That’s a tremendous job. But of the 24 (candidates running for Senate in Louisiana), probably no more than five or six are what I would call … candidates that can win.

“(The tone of the country starts with the president); it does. And look what’s happening right now. The one who wins this thing is going to be the person that people dislike the least. You know, what I found out a long time ago — and it’s just getting worse and worse — more people vote against somebody than for somebody. That’s pretty damn bad when we can’t be for somebody. If you could put one word to it, it’s very depressing.”

Vic Stelly Today

Trim and fit, Vic Stelly looks a very youthful 75. Wearing his blue and gold McNeese polo shirt, he’s got the vigor of a much younger person, and it is readily apparent that he is proud of his accomplishments in life. He says he is very proud of his family, which has extended two more generations from the three children he and his wife Terry raised.

“My family has all turned out to be pretty good people. I’m very proud of all of them. They’ve all done well, and hopefully they’re proud of me. (I have) six grandkids and three of them are adopted. And now we have three great-grandkids.”

While pointing to a photo, Stelly proudly mentions that he has a grandson in Georgia who is coaching.

Stelly stays very active: he plays golf, he says, “for fun. I try to support McNeese the best I can. I follow political things; I try to support people I like.”

Stelly also holds a seat on the board of directors of a bank and is a member of several McNeese booster clubs.

“The Christmas before last, my wife made the statement, ‘I thought we were retired. Every time we want to do something, you’ve got to worry about conflicts.’ (Before retirement) I think I was a member of 8 to 10 different boards and clubs. And so I resigned from everything but the bank board.”

Stelly says he is proud of his 20 years of public life. “I was especially proud of the fact that, in 2006, I was selected to the Louisiana Political Hall of Fame — the first from this area.

“I came through 20 years of public life without any marks against me that I know of. I don’t think I (burned any bridges behind me); it doesn’t seem like I did. I tried not to, and I think I would know. But I feel pretty good about it. And looking back, I feel like anywhere I go I can hold my head high.

“As far as a philosophy, it seems like in (every) stage of my life there was something that needed to be done and somebody had to do it. A lot of times, it was me. The Stelly Plan had no co-authors. You normally try to get as many co-authors as you can to show support. I said that I’m not putting anyone else on the spot. Vic Stelly. One name. That’s it.

“Looking back, something needed to be done. Who would get out and do it; how about me?”

Comments are closed.