HISTORY SHOWS THAT CAR LINES CAN BE POPULAR OONE DECADE; GONE THE NEXT

BY BRAD GOINS

Let’s start with just one letter: the letter A. How many American car makers whose brand names began with the letter A had already gone out of business before the 20th century began?

The answer is three. Before Jan. 1, 1900, three automakers whose names began with the letter A — Altham, American and American Waltham — had come and gone.

Let’s bump up our cut-off date to 1902 and stick with the letter A. We’ll need to add nine names to the list of American car manufacturers that had bitten the dust:

• Altman

• American De Dion

• American Electric

• American Power Carriage

• Anthony

• Armstrong Electric

• Aultman

• Auto Dynamic

• Automobile Forecarriage

In the dozen years between 1895 and 1902, a dozen American car makers whose names started with A came and went.

Why not cover all the letters? There’s a simple and practical reason not to. In the 125 years of American car making, well over 800 American car makers have gone out of business. The list would run much longer than this story.

One of the lies we’ve consistently been told in the austerity era is that companies can be “too big to fail.” There’s ample historical evidence that there is no such thing as an American car maker that’s too big to fail.

The General Motors company was once so admired for its economic power that there was a popular saying about it: “As GM goes, so goes the economy.” No one was saying that in 2008, when GM became involved in bankruptcy proceedings. For many, the almost sickening spectacle of General Motors in bankruptcy negotiations was the event that put the lie to the notion that a company could be too big too fail.

Fortunately for the U.S. economy and auto industry, GM survived the bankruptcy proceedings. But one of its affiliates, Pontiac, did come to an end as a result of the bankruptcy agreement.

In our time, Pontiac manufactured the car that many thought of as the quintessential mass-produced American sports car and muscle car: the GTO. It also created the sports car that had, perhaps, the most passionate of fans: the Trans-Am. In an event that went all but unnoticed, that entire sports car legacy passed quietly out of existence in 2010 for purely financial reasons.

The demise of Pontiac drew just as little interest from the American public as the loss of Oldsmobile had five years before. The history of Oldsmobile, which had been making cars for 111 years, was a venerable one. In 1908, Oldsmobile rolled out the first automobile that was put together on an assembly line. It introduced the automatic transmission to the American car-buying public in 1940. In the last half of the 1970s, the Olds Cutlass was the best-selling car in the U.S.

But three decades later, any lingering customer allegiance appeared to have evaporated entirely.

It’s hard to know when the dissolution of a major American car manufacturer will capture the attention of the public. Certainly, when it began to look as if Chrysler might crash and burn in 1979, the story was trumpeted around the world. When the company was deemed important enough to be bailed out by a loan allocated by the U.S. Congress, CEO Lee Ioccoca was deemed important enough to be considered a national hero — perhaps for his ability to deposit a check.

Another story that seemed to interest the public was the crash of AMC — the American Motor Co. — roughly a decade later.

Perhaps both the Chrysler and AMC stories were of interest because both called into question the idea that the USA economy was an invulnerable world leader. AMC was known for producing compact cars. Did its failure mean that the Japanese were now better than the U.S. at making and marketing compact cars — even in this country?

Stutz Bearcat

Stutz was a much older car line that became famous, then fell by the wayside when financial times got bad.

Stutz was once known as the company that was best at making American sports cars.

The Stutz Bearcat was considered the roadster for the adventurous folk of the day. It brought the concept of “sports car” into American culture. In the 1914 Bearcat, the two front seats looked like the sort of leather seats one would see in a parlor. There was no protective chassis whatsoever around the two seats (and there were no seat belts — in the Bearcat or in any other cars).

Stutz had been innovative from the start. In 1902, it became the first manufacturer to put a steering wheel into an automobile. Before that date, cars had been equipped with a single, long stick-like device that rose up in front of the driver. A second metallic stick was attached to this device at a 90-degree angle. This second short, metallic pole, called a “tiller,” was manipulated by the driver to direct the car.

In 1911, Stutz signaled clearly that it was already anticipating the sports car. A Stutz car was entered in the very first Indianapolis 500. It averaged 68 mph — a stunning achievement for the time.

So what put a company that had anticipated so many demands of the American driver out of business? It was business, pure and simple. The Great Depression killed Stutz. It shuttered its doors in 1934, after only 24 years of car-making.

Other Reasons For Failure

The 1950s saw the decline or demise of giants of the auto industry — Studebaker, Packard, Hudson, Rambler.

In 1953, Hudson tried to resolve its economic problems by merging with the Nash Corp. One result of this merger was the creation of AMC, which created a car that was called, variously, Nash, Hudson or Rambler. Whatever the name, the vehicle was the same.

The 1954 Rambler was the first automobile to have a combination heater and air conditioner (at a cost of $395). The 1958 Rambler American, which now looked different from and smaller than the old Nash, was dubbed America’s first “compact car.”

Again, we see car makers that seem to have a sense of what the car buyer wanted. So why did the Rambler cease to exist?

In the mid-1960s, AMC CEO Roy Abernethy convinced AMC board members that the American public had come to consider the Rambler brand “stodgy,” and by 1969, the model was phased out of the U.S. It is of interest that before he made this ill-considered business decision, Abernethy had worked with two failed automakers: Packard and Willys-Overland, both of which were long gone by 1960. Perhaps his experience caused him to jump the gun and assume that a car was starting to be considered stodgy even though people were still buying it.

But car makers sometimes go out of business for reasons that aren’t fundamentally economic. Perhaps it was the knowledge of that fact that led Abernethy to think that the Rambler had become stodgy. For Abernethy’s former employer — Packard — did, in fact, fail because the American public came to see it as stodgy.

After half a century of success, Packard began to slip after the end of World War II. Packard failed to incorporate style changes being introduced in other makes in the industry. It also failed to produce a car with a V8 engine. It would get by until 1958. But eventually, it was destroyed by the perception that it had become a conservative, old person’s car.

A similar fate befell the Mercury line. Edsel Ford introduced Mercury in 1937 to try to cut into Chevrolet’s dominance of the upper-middle class market. Mercury thrived for decades. But in its last years, Ford failed to bring sufficient innovation to the line. It also came up short in efforts to market Mercury in such a way that it would appeal to car buyers who had a little extra to spend.

The upshot was that Mercury’s Grand Marquis came to be considered an old man’s car in good earnest. The line was wrapped up in 2011. By the time it was out of business, the Mercury line had less than a 1-percent share of the U.S. auto market.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

CASE STUDIES

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Sometimes automobile makers can be too innovative, introducing changes the American driver isn’t yet prepared for. Let’s look at four examples of cars that were a bit ahead of their time — and as a result, were briefly well known and are now long since forgotten.

Smith Flyer

The lightweight wooden platform that made up the floor of the old Smith Flyer was both the body and the suspension of the vehicle.

The engine was mounted above a fifth wheel that constituted the rear of the vehicle. The running engine was placed on top of the fifth wheel, causing it to turn and propel the vehicle.

The motorized fifth wheel was a trend for a while, inspiring the publication of a magazine called the Motor Wheel Age. But this method of propelling a car generated less than 2 horsepower. As interest in the third-wheel motor waned, Briggs and Stratton acquired the motor and used it in lawn mowers and other small pieces of equipment.

Today, the Smith flyer is remarkable for its starkly minimal look. It looks as if it has nothing more than the bare necessities that make a thing a car. But that was reflected in the price. Guinness tags the Smith Flyer as the most inexpensive car ever manufactured. Some models sold for as little as $100. (That was the price for a brand new — not used — car.)

The public’s fascination with fifth-wheel drive was short-lived. The Smith company was finished after four short years. Briggs and Stratton acquired the rights and made more Flyers of its own. But the line would pass out of existence entirely in 1925. It was only 11 years old.

In some ways, the auto industry has yet to catch up to the Smith Flyer. The American buyer has never really warmed to the idea of an automobile that sacrifices all the frills in order to get to the lowest possible cost. Also, the American driver seems set on having high minimal standards for speed and pick-up. On roads marked for 70 mph, no one wants to be going much less than 70.

Stout Scarab

Although to us the body of the Stout Scarab may look like the larvae artist HR Giger designed for the movie Alien, the original design was meant to mimic an airplane fuselage.

The ultimate goal was to make the Scarab an office on wheels. It was a harbinger of such vehicles as the mini-van and sports utility vehicle. It contained such innovations as an interior table and chairs that swiveled 180 degrees.

Today, the Scarab is considered a sterling example of Art Deco design. But at the time, American consumers found it ugly.

Although the frame of the Scarab was made of steel, the body of the first edition sold — which debuted in 1932 — may have been the first made of aluminum. Other models were the first to have fiberglass bodies and use independent suspension systems with coils located at each wheel.

As each Scarab was made by hand, each was unique.

But as innovative as the Scarab was, the American car buyer just couldn’t overcome his aversion to the car’s looks. Enthusiastic press attention couldn’t save the car.

Scarab designed models for the post World War II era, but could never muster the finances to put them into production. After a dozen years of production, the Scarab disappeared. Today, collectors consider it one of the rarest of cars.

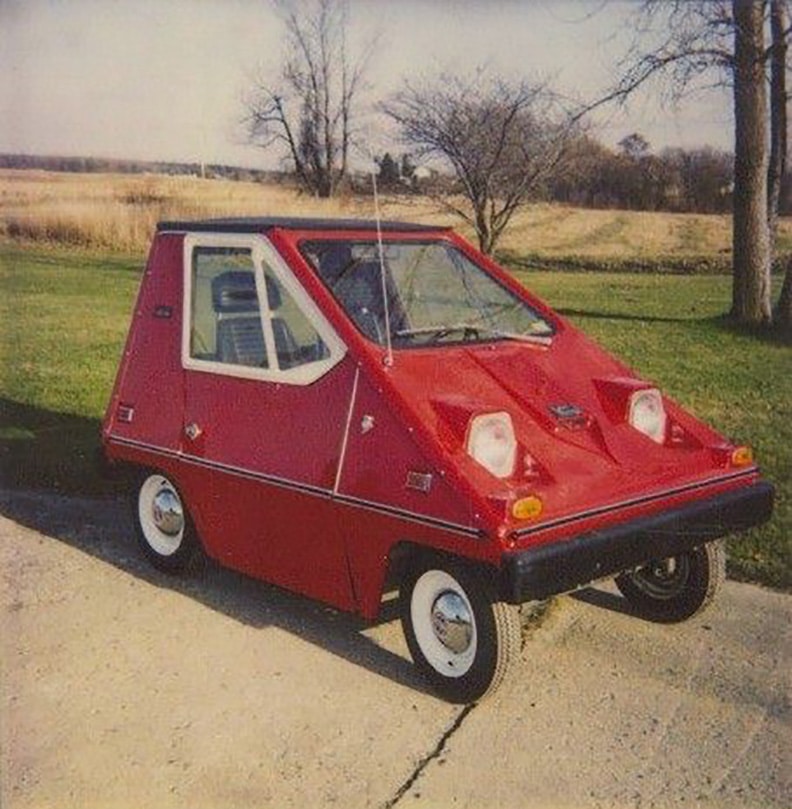

CitiCar

CitiCar was the best-selling electric car made in the U.S. in the 20th century.

The CitiCar was crafted in direct response to the Energy Crisis. Not only was it electric, but it was also small and lightweight. Made of aircraft grade aluminum and ABS plastic, its design was strikingly minimal and simple. The result was good energy efficiency. Its long, straight lines set at extreme angles gave it a quirky look unlike anything seen before; it resembled a geometry textbook illustration of some type of hexagon.

The fastest any CitiCar could go was 34 mph; that was with the CitiCar that had eight 6-volt batteries.

Americans weren’t ready to drive 34, and they weren’t ready for an electric car in the 1970s. By the time of its demise in 1977, a total of 4,500 CitiCars had been sold. Those numbers would be blown away in 2013, when the Tesla Model S gave American drivers the sort of electric car they wanted.

Vector

Speaking of HR Giger’s futuristic designs for 1979’s Alien … automobile junkies may have been reminded of the futuristic Vector when they saw such vehicles as those created for Disney’s sci-fi flick Tron (1982) or the wildly angular Batmobile created for Christopher Nolan’s Batman movies of this century.

The idea of the Vector was formulated by Hollywood designer Gerald Wiegert in 1971. Wiegert thought there was no reason the U.S. couldn’t manufacture such super-powered and sleek sports cars as Europe’s Ferrari and Lamborghini.

The Vector’s long and low angular lines gave it an otherworldly look that must have appealed to some fans of Formula 1 race cars. The affluent sports car lover was definitely interested.

Wiegert had a working prototype ready by 1979. He claimed the car was capable of reaching 230 mph, but asked car magazines, such as Motor Trend, not to test it at that speed.

That may have been the beginning of Vector’s early woes, which usually boiled down to performance.

Each Vector automobile was handmade. It took a lot of time to make a Vector, and each one was extremely costly for any would-be consumer.

Something about the new concept appealed to tennis star Andre Agassi, who pressured the Vector company to get his car to him quickly.

Agassi got his car delivery, but was also warned to avoid driving at high speeds. The adventurous athlete ignored the advice and put the car’s engine through a process of self-destruction. Vector gave back Agassi’s $500,000 and got a lot of bad press.

Vector had problems producing more than 20 vehicles a year. The company’s finances were so shaky that an Indonesian company acquired it in 1993 and fired Wiegert. Some observers felt the Indonesian company made questionable moves with what little money Vector had.

The new owners gave up the performance battle and decided to put a Lamborghini V12 engine in the Vector, at this point called the Vector M12. Although the car was made in Florida, the new Italian engine put to rest the Vector’s efforts to create an American super sports car.

By the end of the 20th century, Lamborghini quit delivering its engines for the simple reason that Vector didn’t have enough money to pay for them. Wiegert was able to regain control of his beloved company. As recently as 2008, he displayed a prototype of a Vector at the Los Angeles Car Show, claiming that the vehicle could travel at 275 mph. But this time, no one was allowed to test drive the car. As far as this writer knows, no one has bought a new Vector in the 21st century.

Investment Trumps Economizing

There’s no one reason auto makers fail. Sometimes failure can result from an unpredictable coincidence of factors, such as a poor design decision that occurs in tandem with an economic turndown.

If there’s one major lesson to be drawn from the failure of car lines, it could be this: once a car line has been accepted by the public, that acceptance should be respected and nourished.

The auto industry produces more revenue than any other segment of the U.S. economy. Because much is wanted, much must be produced. Price increases in such key materials as steel or fuel, as well as an effort to respond to consumer trends and demands (such as those for high-tech accessories) can tempt large-scale auto companies to cut and streamline in order to reduce costs. When cuts interfere with the consumer’s ongoing desire to get what’s new, problems can arise.

Fortune’s Alex Taylor recently wrote that “maintaining a strong brand requires constant investment. That’s particularly important in autos, where the opportunities to economize are ever present — and often fatal.”

Comments are closed.