A Newcomer’s Introduction To The History Of Lake Charles

By Brad Goins • Photo By Lindsey Janies

Somewhere near the beginning of the story of Lake Charles, Jean Lafitte makes his entrance. Lafitte was a famous and successful pirate (or “privateer,” if you prefer).

It’s said that Lafitte began his career as a lawyer or shipping agent in New Orleans. When he saw how corrupt his clients and the system were, he decided his best bet for financial success would be to become corrupt himself. He eventually acquired his own fleet of ships and ran it his way.

Lafitte was successful in using his army of pirates to defend his city in the Battle of New Orleans (1814). Three different films have been made about the exploit, the best-known of which is 1958’s The Buccaneer, in which Yul Brynner plays Lafitte.

Lafitte loved to hide his boats in the meandering bayous around Lake Charles long before settlers in the area had given the tiny settlement a name. In the first two decades of the 19th century, Lafitte often visited the houses on the shore of what would become Lake Charles. He was, we think, a close friend of Charles Sallier, the early settler whose name would eventually be given to Lake Charles.

It’s said that Lafitte was more than a close friend to Sallier’s wife. But we can’t know for sure whether that’s true. Indeed, much of Lafiitte’s story is obscured by the fog of myth and grandeur that swirls around the life of any famed pirate. Even today, historians debate the authenticity of basic events in Lafitte’s story.

One thing we know for sure — Lafitte’s presence in Lake Charles was a strong indicator of the economy the community developed long before it became a city. Before the Civil War, the business of Lake Charles was centered around those who traveled up and down the Calcasieu river. The community was a haphazard collection of houses and shacks that ranged along the coasts. The tiny populace was oriented toward bartering, selling or otherwise doing business with those traveling on the river.

It wasn’t until the end of the Civil War that the community was large and organized enough for incorporation. In 1865, the town was incorporated with a population of 5,000. Before it became known as Lake Charles, it was known as Charleston.

It wasn’t until wealthy entrepreneurs realized that Lake Charles was an ideal site for a timber industry that the city experienced its first major population boom. Eventually, the area’s longleaf timber became so highly prized that it was marketed throughout the country as “Calcasieu pine.”

Many of those who led the construction and operation of the city’s numerous lumber mills were settlers who had moved down to the city from the U.S. Midwest. In particular, German architects came to Lake Charles to shape the timber industry and the homes of those who would lead it.

It was these architects who were responsible for the distinctive and lavish design of homes in the city’s historic Charpentier District. Many of the elegant homes they designed have been preserved, and are still celebrated and toured today.

Lake Charles’ turn-of-the-20th-century-architects created a brand new architectural feature that is known the world over as the Lake Charles Column. The column is marked by its square (rather than circular) shape; its paneling; and a slight tapering that takes place as it rises. One can see many examples of it in the Charpentier District.

Many of those who moved to the area became known as the “Michigan Men.” Because of such imports to the area, it’s still thought that the unusual mix of people from different cultures gives Lake Charles a cultural diversity that other parts of Louisiana lack.

‘Battle Row’

As the 20th century got underway, there were two predominant cultures in downtown Lake Charles. One was the culture of the affluent architects, bankers and lawyers who settled into large, quiet houses on Pujo and Kirby Streets. The other was the loud, loose culture of timber and railroad workers that sprang up further north on Railroad Avenue.

Though it is desolate today, a century ago, Railroad Avenue was a raucous row of saloons, brothels and gambling spots. It was awash in liquor and crackling with violence. More than a few people were murdered outright on the street. Fist fights took place as a matter of course.

The stretch of road became known as “Battle Row.” The city had given the area the official designation of “red light district” in an effort to confine prostitution to one area. This effort was rescinded by city government in 1918.

Decade Of Disasters

By the end of the 1910s, many in Lake Charles must have wondered whether they were being punished for some great offense; or, perhaps, whether they had stumbled into the end of the world.

Of course, in the course of the decade, the city went through the same two great disasters that every other U.S. city of its size went through: the first World War (1914-18) and the Spanish Flu (1918).

But Lake Charles experienced two other great catastrophes in the 1910s: one regional and one entirely local.

The Great Fire of 1910 burned down more than 100 structures in downtown Lake Charles. It began when a worker burned some trash in the alley behind a downtown theater.

Much of the downtown was rebuilt (under new city codes requiring certain percentages of brick and stone). But before the work could be completed, the city was struck again — this time by the Hurricane of 1918. In addition to extensive damage downtown, local homes and 10 local mills were destroyed. It was the last nail in the coffin of Lake Charles’ dying lumber industry, which had, in effect, deforested the city and its surroundings.

After 1918, many felt they’d had enough, and there was a brief exodus from Lake Charles.

A Bit Of Secret History

The 1915 census found the population of Lake Charles sitting at 18,000. At that time, the majority lived north of Division Street. The city had seven miles of paved roads. The speed limit was 8 miles an hour. Lake Charles had a total of 1,500 telephones.

If the socialists thrived, so did the Ku Klux Klan. In a 1922 rally that took place on Broad Street, 300 were sworn in as members in front of a group of 800 who were already wearing white robes. And a 1923 Klan rally in Lake Charles attracted an audience of 25,000 — a crowd that certainly put Debs’ to shame.

There were no news reports of violence at these rallies. However, for what it’s worth, when John J. Robira was campaigning for Lake Charles DA in 1924, he stated, “My two biggest problems are the Ku Klux Klan and the moon shiners.” (This statement is recorded in chapter 2, part 9 of local historian Nola Mae Ross’ book Crimes of the Past in South Louisiana.)

A Brilliant Business Solution

After the timber industry all but disappeared, the rice industry remained important to the city. In the 1920s, Lake Charles had the largest rice mill in the world. For a few years in the twenties, the city hosted the Rice Day Carnival.

But the local rice industry was rapidly shrinking. It had boomed as World War I created an international demand for rice. With the war over, so was the unusual demand.

When assistant D.A. Sam Jones (who would later become governor of Louisiana) assessed Lake Charles in the 1920s, he found the city was “economically pretty well run down.”

At the time of Jones’ utterance, a solution had already been found. By the early 1920s, local political leaders were talking with great enthusiasm about a concept they called “deep water.”

The idea was to give even the largest of boats access to Lake Charles. One century on, the city would return to an economy built around shipping and transportation via water.

With new local and state legislation and assistance from the U.S. Congress, the Intracoastal Canal that connected the Calcasieu and Sabine Rivers was deepened to the point that it could serve as a ship channel.

As the Port of Lake Charles was being built, silt was dredged from the Calcasieu River. A deep water channel to the Gulf was completed in the same year as the Port of Lake Charles — 1926. Big boats could now sail just 35 miles from the Gulf of Mexico to dock in Lake Charles. Lake Charles could compete for import and export business on the same playing field as the Port of New Orleans and the best ports of east Texas.

As the city moved into the World War II era, it experienced an influx of oil refineries and chemical plants that could use products from, and deliver products to, the refineries. The petrochem industry was spurred by the massive demands for fuel on the part of the U.S. military and its allies in the war. The presence of a deep water port, and a tremendous supply of both oil and natural gas, made Lake Charles and Westlake especially attractive spots for wartime work.

Culture — High And Low

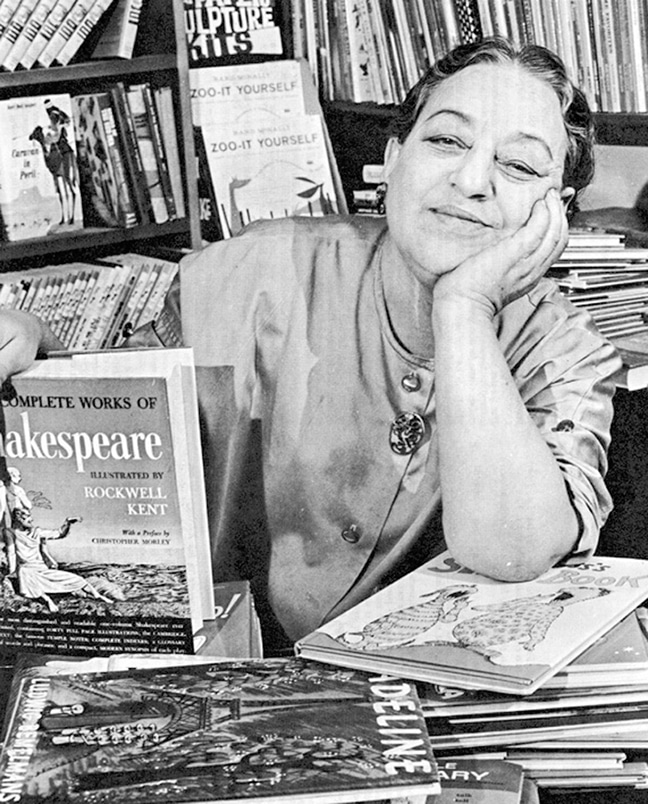

In 1927, Rosa Lucille Hart organized the Lake Charles Little Theater, which she directed for the next 30 years.

Hart was conversant with the most modern and experimental trends in theater. She would have to have been, as she counted among her friends the likes of William Faulkner, H.L. Mencken, Charles Laughten and Vincent Price. Her salon became the gathering place for the growing city’s intelligentsia and creative set.

While local wits discussed theater trends in Hart’s salon, many on the popular porch of the Majestic Hotel may have talked about the latest Hart production being staged in the hotel at the time.

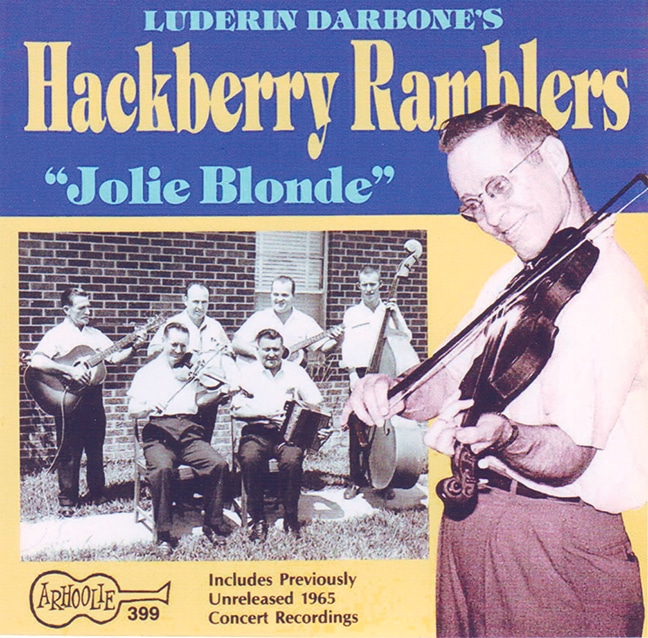

But many men, wearing their seersucker suits and holding their big cigars as they rocked in their chairs, might just as well have been talking about the new local band Luderen Darbone’s Hackberry Ramblers. Everyone in town knew that the Hackberry Ramblers had had a $60 sound system shipped all the way from Chicago. It only made their popular Cajun anthems — “Jolie Blonde,” “Lafayette” and “Hi-dee-hi” — sound better.

As Lake Charles acquired more residents and more modern technology, it eventually became a regional leader in both the high arts and the popular arts.

KPLC brought modern radio to the Lake Area in 1935. KPLC became an NBC affiliate 10 years later, and a television station 10 years after that.

Not all who’d been influenced by the Hackberry Ramblers, the Lake Charles Playboys, and the many other roots musicians in Lake Charles, stayed in the area. When she reached adulthood, Nellie Lutcher left Lake Charles for Los Angeles, where she became a well-known popular singer and songwriter.

But her brother, “Bubba,” stayed behind to become the Lake Area’s first black disc jockey, spinning his sides at KAOK in the 1950s. Forty years later, Faye Browne Blackwell would become the area’s top organizer of black entertainment in the area. She founded KZWA in 1994; also founded the Martin Luther King Foundation; and continues to organize or support many events related to black music or culture.

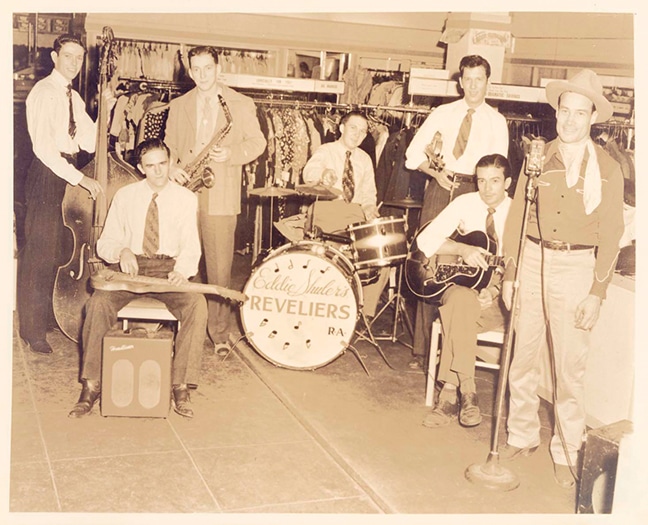

Not long after Bubba Lutcher got his DJ gig, Eddie Shuler established Goldband Records, which gave the world some of the best-known swamp pop, Cajun and “old timey” music singles, as well as the first recording by Dolly Parton and early records by Freddy Fender. Shuler had a major national hit in Phil Phillip’s 1959 single “Sea of Love.”

It would be a monumental task even to list the many masters of swamp pop, Cajun, zydeco, Creole and “old timey” music who grew up in Lake Charles. Many still perform here regularly; some in spite of old age. Every weekend, seasoned masters of Cajun music, zydeco and swamp pop perform in at least three or four venues in the city.

The Lake Charles Symphony gave its first performance in 1958 with an orchestra of 70. After Bill Kushner conducted the symphony for many years, it found a worthy replacement in the young and charismatic Bohuslav Rattay, who came to the symphony after he’d already directed many of the major works of the modern masters in key European venues.

Lady Leah LaFargue created her Lake Charles Civic Ballet Company in 1968. The troupe remains vibrant, continuing to generate both original choreography and original musical compositions for its performances.

Four years later, locals Lamar Robertson and Donald Allured founded the Louisiana Choral Foundation, which still performs on a regular basis.

Economic Diversity

In the decades following World War II, the Lake Charles petrochem industry continued to develop, although it followed a far more conservative model than the one used by neighbor Lafayette.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the city’s leaders envisioned an economy based on the creation of a large retirement community in Lake Charles. Hopes were for a steady stream of such performers as Mel Torme and Robert Goulet at the newly created Lake Charles Civic Center.

This plan, too, proved to be excessively conservative for the business realities of the time. The city was thrown into near-depression in the 1980s, when the oil bust sandbagged its biggest, most reliable industry. Again, economic conditions caused something of an exodus.

The city again pulled itself out of a deep business hole with a clever business innovation — in this case, diversification that would give Lake Charles two entirely new major industries.

In 1987, the newly retooled Chennault International Airport completed its first project — the completion of a Boeing refueling aircraft. Even though many of the projects undertaken at Chennault are contract projects, overall business at the facility has usually grown at a brisk rate, with the focus remaining on aircraft-oriented services, and in particular, projects related to the defense industry.

In the mid-1990s, the second new industry was worked into the diversification scheme. Players Casino (later Harrah’s) and Isle of Capri Casino opened in Lake Charles. Twenty years on, L’Auberge has just completed its first decade of gaming and Golden Nugget just joined the casino club.

The tri-partite economy of petrochem, Chennault and gaming has given the Lake Area an economy that’s stable. Fuel, aviation, defense aircraft and gaming are all, as a rule, recession-proof. The ability of this combination of industries to create a steady demand for jobs regardless of financial trends accounted for the fact that Lake Charles made it through the Great Recession much more easily than most cities its size.

It is now thought that a coming boom of energy construction projects may create an entirely new type of economy for Lake Charles. As Lake Charles moves into yet another major economic re-invention, the changes that come and the efforts to adapt to them may shape the next chapter in the city’s history.

Comments are closed.