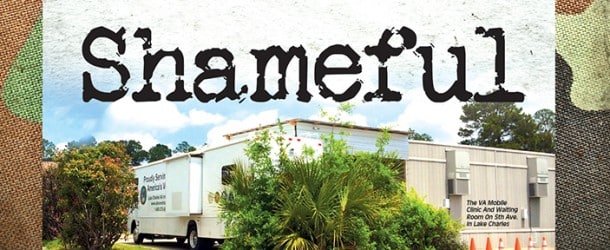

The VA Has Failed Yet Again To Provide A Permanent Medical Clinic For Local Veterans. Our Vets Deserve Better Than A Camper. What’s The Hold Up?

Was it a gesture of disrespect or disregard for Southwest Louisiana veterans? Was it something stronger — like a slap in the face? Or was it just one more instance of chronic disorganization on the part of the Veterans Administration?

It was good news for Lafayette, of course. Problem was, many — area Rep. Charles Boustany among them — had been expecting that the construction of a permanent clinic for vets in Lake Charles would be announced on the same day.

The news for SWLA could hardly have been more disappointing.

On that bleak March 27, the VA announced that the dates for the leasing and opening of a permanent Lake Charles vets clinic would be pushed back once again.

According to an article by David LaCerte, secretary of the Louisiana Dept. of Veterans Affairs, the VA’s excuse for pushing back work on a new VA clinic for the city was that the VA failed to get a lease for a building that could house the facility. (LaCerte’s article can be found on the Department’s web site.)

Anyone who knows Lake Charles at all knows that there are dozens of commercial buildings of all shapes and sizes for rent within the city limits. Why would the VA in particular be unable to secure a lease on one of these buildings? You or I could certainly do it easily enough.

Right now, the VA contends that the first Lake Charles vet will be seen in the new Lake Charles vet clinic in June of 2016. Unfortunately, there are hundreds of vets and vet sympathizers in the area who feel the date will eventually be pushed further back.

On the up side, pro-vet activists in the area are working hard to keep the VA focused on that opening date — and perhaps even on finding its way to an earlier one.

Deja Vu All Over Again

For many local vets, the March 27 announcement was a case of deja vu all over again. They remember that when Lake Charles got its first clinic — a clinic on wheels — the action came about a month after plans to build a permanent clinic in the city fell through.

And what was the reason they fell through? It was the very same reason the VA provided a few weeks ago — “errors during the proposal process” was the phrase the American Press used at the time.

A mobile clinic was, one guesses, a way to deflect attention from the fact that the VA didn’t seem able to negotiate basic bureaucratic procedures.

Many vets, politicians and others must be wondering: What is it that prevents the VA from going through a bids process that most federal agencies navigate with relative ease? Although the answers won’t make you feel especially good, Lagniappe will provide them in this story.

‘The Camper’

A mobile VA medical clinic opened its doors in Lake Charles in Spring of 2012.

At first, the rolling clinic drew high praise from a number of prominent local figures. Perhaps they figured it was a sign of good things to come; or perhaps they figured that something was better than nothing. After all, the clinic would provide a certain amount of medical care to vets who came to it. It was only primary care — but that’s better than nothing, right?

But it turned out to be too little too late. As reports of VA inefficiency nationwide spread like wildfire through the national and international media, the LC portable clinic became the center of powerful national media attention.

The most intense focus came from a CBS News story about the mobile clinic. One year after the clinic opened, CBS reporters came to Lake Charles to interview Deron Santiny, an Iraq War veteran. Santiny obviously saw the clinic on wheels as an affront to local veterans. He derisively called it a “camper.”

“Veterans deserve more,” Santiny told CBS.

The network story reported that any Lake Charles vet who chose not to use the clinic would probably wind up traveling at least as far as the VA hospital in Alexandria — and possibly all the way up to Shreveport.

In a story on the CBS segment, The American Press reported that local U.S. Rep. Charles Boustany had been “instrumental” in attracting CBS to the story. The Press also noted that Boustany has 13,000 vets in his district. (The total number of vets in the five-parish Imperial Calcasieu area is 40,000.)

Call it a “camper” or whatever you like, the current vehicle is the office space for one doctor, one nurse and one LPN. And even with that short staff, they’re cramped.

The VA limits the number of patients the doctor can see.

But, says Louisiana American Legion Vice Commander James Jackson, who works out of Lake Charles, the staff that is there is hard-working and concerned about local vets.

“The people are fabulous,” says Jackson. “They’re beyond good.” But there’s only so much they can accomplishment in three rooms that aren’t much bigger than walk-in closets.

Starting Over Again

Fast forward a year and a half. After widespread expectations for the long-awaited news of a permanent LC clinic, all that came was a terse announcement of one more postponement.

The reaction after the VA’s March 27 failure to launch was not ambiguous. Rep. Boustany said the delay was “absolutely unacceptable,” while Sen. Vitter called it “nothing short of tragic.” KATC reported that Vitter also said the VA was in “disarray.”

Boustany said he’d be working with Vitter to set up a conference call with VA Secretary Robert McDonald to “demand answers.”

“It’s very aggravating, all this being put off,” former state Rep. Vic Stelly told Lagniappe. “I do have a lot of friends who are affected by it and they are not very happy.”

Mayor Randy Roach told Lagniappe his work with the VA to secure a site for a permanent clinic would continue. “The City of Lake Charles has suggested a number of suitable sites for the clinic. As a community, we have coordinated a grassroots effort between veterans, their families, local elected officials, our area’s legislative delegation and our elected officials in Washington to communicate the need for a local clinic.

“The VA should do whatever is necessary to speed up its process. The clinic was originally scheduled to be completed in 2009. The time for action is now. Our veterans have waited long enough … Since the need for a veterans clinic in Lake Charles was first discussed in 2000, we have been prepared to do whatever it takes to accommodate the Dept. of Veteran Affairs.”

After the dismal March 27 news broke, the VA asked James Jackson to try to find three medical properties in the city that would be appropriate for the VA’s needs. He did so. If the VA decides that it likes Jackson’s choices, then the bidding process can start all over again.

If bids are put out again, they’ll start with a 30-day request period, followed by a 30-day (or longer) evaluation period.

Don’t expect it to be a speedy process. The city could see a VA clinic in a brick and mortar structure by the Summer of 2016 — but “that’s if everything works perfect,” says Jackson. He thinks the facility “probably” won’t be available until late 2016.

Some of the clinic news is less discouraging. For starters, there’s the consolation of knowing that there are good people elsewhere in the Louisiana VA system. I’ve heard several local officials state that Jimmy Murphy, the deputy director of the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System, is deeply concerned about SWLA vets.

Jackson, who’s also impressed with Murphy, says simply, “He’s going to make changes.”

Area District Attorney John DeRosier tells Lagniappe that Murphy is actively involved in efforts to facilitate the next round of VA bids for a permanent LC clinic.

After early April meetings with a group that included reps from the offices of Rep. Boustany and Sen. Vitter, DeRosier said, “I’m much more confident now that this process is going to happen. I think it’s going to work.”

DeRosier thinks the VA could have a permanent clinic operating in Lake Charles as early as October of this year.

The bidding process the local VA is beginning, says DeRosier, is an “RLP” — or a “request to lease property.” As part of the process, the local VA will be announcing in print that it is in search of properties. The general public can respond to these announcements.

Jackson notes that the last time Lake Charles bids fell through, the VA did not begin a new round of bids; rather, it chose to “refresh” the old bids. In theory, this meant that the VA was continuing to pursue — in some way or other — the old, failed bids. This “refreshing” process went on more than a year.

The federal government has mandated the establishment of the permanent LC clinic. After the recent VA scandals became known, the feds made it clear that more than 29 permanent VA clinics that had been promised around the country were, in fact, to be constructed. Federal law now requires it.

‘A Culture Of Complacency’

After all, the VA is only one department. It can’t really thumb its nose at the rest of the federal government, can it?

As astonishing as it may seem, history suggests that is a distinct possibility.

With 300,000 employees, the VA is the second largest department in the U.S. government. That department now has a budget of $150 billion to work with.

Are vets getting their fair share of the $150 billion? It’s one thing to be told that at Atlanta’s VA clinic, investigators know of four veteran deaths that could have been prevented with proper medical care. It’s another thing entirely to learn that during the period of these deaths, clinic director James Clark received $65,000 in bonuses.

Not shocking enough for you? How about this one? Diana Rubens is the VA exec who oversees the processing of disability benefit claims on the VA. During her tenure, the number of backlogged claims has increased by 700 percent. Yet in the same period, she collected $60,000 in bonuses.

Many blame middle management in the VA for the group’s problems. Managers and executives can receive regular, generous bonuses through an incentives program. But the requirements for the incentives are vague. And many assume that if middle managers are content to take home bonuses while a center is clearly disorganized, it’s little surprise if low-level workers decide they aren’t obliged to meet high standards in their work.

The sort of situation being described here is obviously one of a corporate — or in this case, departmental — culture.

The chairman of the House Veterans Affairs Committee, Rep. Jeffrey Miller (R-Fla.) has called it a “culture of complacency” and “an embedded culture.” He told the International Business Times, “these mid-level managers [of the VA] know that as federal employees, there is a good chance they’ll have their position longer than I will be chairman of oversight … They’re evidently willing to just wait out those of us who are trying to change things …”

Congress struggles mightily to whip the VA middle management into shape. Part of the effort was the recent passage of the Choice Act, which was sponsored by Sen. David Vitter.

But nothing seems to stick; nothing seems to bring about reform. The VA just blew a great chance to show that it was ready to crack down on inefficient middle management. In November of last year, new VA Sec. Robert McDonald announced he would fire 1,000 VA managers thought to be at the heart of the department’s highly publicized medical scandal.

In a Feb. 15 Meet the Press program, McDonald asserted that he had made good on his promise. In fact, he said, he had already fired 900 VA managers. He fired 60, he said, who were directly linked to the medical scandal.

Skepticism about the claim set in immediately. “No, the VA has not fired 60 people for manipulating waiting lists,” stated the Washington Post, which published a story that presented the correct figures three days after McDonald’s TV appearance. The differences from McDonald’s statement were stunning. Only eight people in the entire VA had been fired for the medical scandal.

In its well-known “Fact Checker” section, the Post gave McDonald Four Pinocchios — its worst rating for false or misleading statements. The Post calls comments that get four Pinocchios “whoppers.”

Asked to explain McDonald’s claims on Meet the Press, a VA representative said he had “misspoke.”

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

No Policeman On The Block

Could Congress pass a law requiring that a certain number of VA managers be fired? One presumes it could.

But could Congress enforce its own act? The International Business Times (“VA Is Broken,” Nov. 27, 2013) paraphrased Thomas Bandzul, an attorney who represents the group Veterans and Military Families for Progress, as asserting that the VA is “a rogue agency with few constraints and no one inside or outside … to compel the department to improve.”

Says Bandzul, “If a law is passed that calls for changes, it has to be enforced. And there is no enforcement within the VA system … Even the courts have extremely limited jurisdiction. Simply put, there’s no policeman on the block to make the VA behave.”

“Does Congress have any real authority [over the VA]?” asks Jackson. “The answer is no.”

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Close To Home

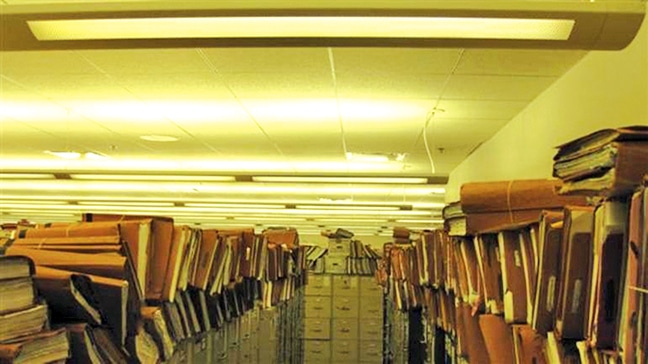

Jackson maintains that the national VA owes Louisiana medical facilities $58 million for medical services performed. That $58 million is the result of 300,000 standing Louisiana claims on the VA. One Louisiana hospital alone is owed more than $2 million of VA money.

The VA has a budget of $150 billion. Why not just pay the $58 million?

Nothing is simple about VA bureaucracy. “They have the money to pay the bills. They can’t process it,” says Jackson. “The VA has an archaic management system.”

The VA has worked with two agents who failed to pay the Louisiana claims. A new, third, agent, stationed in St. Louis, maintains it has paid 100,000 of the 300,000 claims. But Louisiana hospitals are still waiting to see a check.

What about claims in Louisiana — and around the country — that were filed before the 300,000 that are still in play in this state? Jackson claims the VA maintains that claims it just never got around to are now “too old” to be paid — that they were not submitted in “a timely manner.”

Jackson calls the approach “irrational.” “Who knows what goes on in these negotiations [about claim payments]?” he speculates.

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

‘We’re Not Giving Up’

Readers probably won’t be surprised to learn that Jackson is a vet himself. He did two tours of duty in Vietnam. He is 100 percent disabled, with one of his biggest health challenges being serious diabetes. Now retired, he can get health care from a variety of sources. But he often chooses to deal with the vets’ hospital in Alexandria — just to keep them on their toes.

“We’ve been working on this [clinic in Lake Charles] 13 years. You get frustrated working with the VA.

“We’re not giving up. We’re not going to back down from them.”

But can the VA be trusted to finally get serious about a permanent LC medical clinic this time around? “They have got enough political pressure that they will in fact make a good faith effort to get one of these buildings,” says Jackson.

Even this will not be entirely good news for local vets. With the local population set to increase — according to some predictions — by as much as 40 percent in the next decade, “the clinic will be obsolete by the time it’s built,” says Jackson.

“We have thousands and thousands of young vets. Why are we not providing their care?

“The vets are struggling to make the best of a very bad situation. We really need the public to get behind the vets.”

Vets themselves must become more vocal, says Jackson. “We were trained to follow orders; not to rock the boat.” That approach often will not yield positive results when it comes to interactions with the VA.

“The debt we owe to our nation’s veterans is tremendous, as they risked their lives to protect our freedoms,” says Mayor Roach, expressing what are very widespread sentiments about vets in this area. “We must help deliver a permanent Lake Charles community-based outpatient clinic for the veterans in Calcasieu Parish.”

“It’s inconceivable that a proud nation won’t help those who did their duty,” says Jackson. And in fact, anyone with any sensibility at all must admit that it is at once absurd, ironic and sad that U.S. veterans must fight against the one agency whose sole purpose is to provide for their well-being.

Comments are closed.