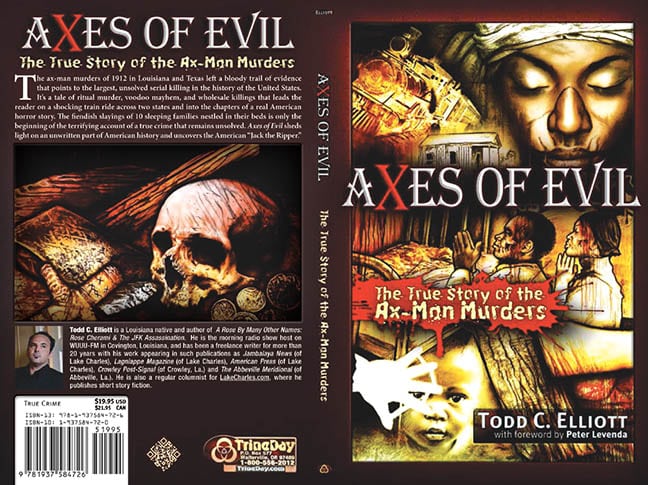

Walterville, Oregon: Trine Day, 2015.

143 pages. $19.95. Illustrated by Hal Moore.

La. Author Todd C. Elliott Tells The Story Of A Serial Killer Who Stopped In L.C. One Fateful Night A Century Ago

With the publication of his new book Axes of Evil, Todd C. Elliott stakes out his place as the paramount true crime writer of Southwest Louisiana. (Any who feels he is the only true crime writer in the area may wish to read the late Nola Mae Ross’ fascinating volume Crimes of the Past in South Louisiana.)

In Axes of Evil, Elliott teases out a case very similar to the one he painstakingly examined in his first book A Rose by Many Other Names: Rose Cherami & The JFK Assassination. That work looked at a possible connection between the south Louisiana prostitute Rose Cherami and the shooting of John F. Kennedy — a connection whose story was so fraught with drama and mystery that director Oliver Stone portrayed it in his movie JFK.

The case in the new book — that of the Ax-Man who plagued Southwest Louisiana a century ago — is similar to that of Rose Cherami in a broad sense. Both cases were set in obscure, out-of-the way places. Both are full of eerie details and bizarre coincidences that are hard to explain. As a result, both cases retain a decided air of mystery, and are more than a little creepy.

There are some differences, though. While the events in the Rose Cherami case take place on lonely rural highways or back roads, all the incidents in Axes of Evil occur in close proximity to rails that were used frequently by prominent railroads, and especially the Southern Pacific.

If law enforcement agreed on one thing about the Ax-Man case, it must have been that the Ax-Man traveled by train. Whether by coincidence or not, several of the suspects and victims were affiliated with railroad lines.

To a large degree, the Ax-Man murders followed a set pattern. Each murder was of a black family living in a house. All victims were killed by blunt force trauma to the head inflicted by a pole ax (an ax whose metal head is sharp on one side, blunt on the other). The killer never brought his own ax; rather he used an ax owned by the family or a neighbor. Each ax was left on the premises after the murder.

All the victims were arranged in one or more beds after they were killed.

In each case, the back door was left open.

Nothing was ever stolen from the houses.

Of course, as in any case of this type, it’s the peculiarities of certain crimes that are the most interesting aspects of the case. And there were peculiarities to spare in the Ax-Man crimes, with many of the strangest features occurring in the Lake Charles murder, which took place in January, 1912.

Before we consider just what made the L.C. murder so unusual, let’s get a little context with a chronology of murders committed by the Ax-Man in both Southwest Louisiana and Texas.

September [?], 1910: Rayne. Wexford family of three killed.

Jan. 26, 1911: Crowley. Byers family murdered. Three victims.

Feb. 23, 1911: San Antonio. Cassaway family murdered. Five victims.

Feb. 24, 1911: Lafayette. Andrus family murdered. Four victims.

Nov. 27, 1911: Lafayette. Randall family murdered. Five victims.

Jan. 19, 1912: Crowley. Marie Warner and her three children murdered.

Jan. 22, 1912: Lake Charles. Broussard family murdered.

Feb. 19: Beaumont. Hattie Dove and her three children murdered.

March 26, 1912: Glidden, Texas. Monroe family murdered.

April 12, 1912: San Antonio. Unidentified family of five killed.

April 12, 1912: Hempstead, Texas. Unidentified family of three killed.

Elliott calculates that the murders in these locations yielded a total of 45 fatalities.

What will strike many people about this timeline is that the killer struck in San Antonio on one day and in Lafayette the next. As always with this case, one must assume that the killer was someone who had access to trains and was comfortable with riding them for long distances.

The Lake Charles Murder

Felix and Matilda Broussard, and their three young children Margaret, Louis and Alberta (or “Sissie”) were killed in typical Ax-Man fashion. They lived at what was, at the time, 331 Rock St. in North Lake Charles in a small house a few feet from the tracks of the Southern Pacific Line. The tracks are still visible on the lot today.

While the case followed the general Ax-Man pattern, it was also full of anomalies. This was the only murder site at which the Ax-Man may have left written messages. On a door was the handwritten Bible verse: “When He maketh the inquisition for blood, He forgetteth not the cry of the humble” (Psalm 9:12). Under the verse was written the name “Pearl Ort” or “Art.”

Calcasieu Parish Sheriff David John “Kinney” Reid told the press he believed the Bible verse was written at some time before the murder. But that belief didn’t prevent Reid from conjecturing that the crime had been committed by a “religious fanatic.”

Adjacent to the verse were the handwritten word “Human” and the numeral “5.”

While those words could have been written by anyone at any time, what couldn’t have been done by anyone was the affixing of truly bizarre decorations to the child victims’ fingers. Each finger was pushed apart from the other with rolled up pieces of paper attached by pins. Whatever this was meant to convey, it certainly called attention to the fact that each human hand has five members.

In the local hysteria that followed the murder, there was widespread speculation that the murders were committed by a radical religious group or sect called the “Human 5.”

Reid may have recognized a religious element in another unique aspect of the Lake Charles crime scene: a bucket had been placed under the bed of the Broussard children to catch the blood as it dripped. Some thought the collection of blood was part of some sort of sacrificial ritual.

Mother Matilda Broussard was believed to have attended a revival meeting of the Sacrifice Church that had recently taken place in Lake Charles. Police in Lake Charles would have known that the Ax-Man murders had long been connected with the Sacrifice Church, which was also called the Sanctified Church, the Sacrifice Sect, the Flame of God Church and (in New Orleans) the Council of God.

Jennings police had arrested one person affiliated with the church; Lafayette police had arrested two; and after the Broussard murder, Lake Charles police detained two.

One of these, Ed Jiles, was described by the March 1, 1912, American Press as a “giant” black man who was “crazy-acting.” Jiles didn’t speak at all, but did use hand signals, which detectives may have felt were somehow related to the oddly decorated hands of the Broussard child victims.

The second suspect, A.E. Anderson of Moss Street, did talk with law enforcement, explaining that he was a “preacher” in the Sacrifice Church.

Elliott notes that on April 9, 1912, the Lake Charles Daily Times reported that the “Sanctified Sect of the Sacrifice Church” was converting blacks in Lake Charles in large numbers.

The Times reported on a Lake Charles Sacrifice Church “preacher” whom it called only “Thompson.” Thompson was said to have preached to his Lake Charles congregations that members of the church were “sanctified,” and thus could not commit sin regardless of whatever man-made laws they broke.

Police found that in his Bible, Thompson had underlined a verse in Matthew: “And now also the axe is laid unto the root of the trees: every tree therefore which bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire” (Matthew 3:10).

Elliott explains that it gradually came to be thought that some in the Sacrifice Church – and the Ax-Man in particular — interpreted the verse as meaning that the trees that didn’t bring forth good fruit were light-skinned blacks or blacks born from the marriage of a white and a black. Victims of the Ax-Man were almost uniformly said to be light-skinned blacks. Such a belief, skewed as it was, might have been in keeping with the times. In the course of his research, Elliott learned that the first International Eugenics Conference was held in London in the same year as the Lake Charles Ax-Man murders — 1912.

The widespread belief that the Ax-Man chose his victims in advance at revivals or other meetings of the Sacrifice Church still seems plausible today.

Panic

Panic about the Ax-Man wasn’t confined to Lake Charles; nor was the belief that the killings had something to do with religion.

“In every Negro house in Crowley, lights are kept burning all night and adult family members remain awake during the night,” wrote a reporter for Crowley’s Daily Signal on Jan. 22, 1912.

The Signal also reported that “Many believe that religious mania is responsible for the killings … Negro servants in Crowley are in a panic … The more superstitious believe that some supernatural agency is at work.”

Before the Lake Charles murder of the Broussards, hysterical fears about the role of the Sacrifice Church had been stoked in Crowley and Lafayette. We will see just how widespread these fears became in Lafayette.

Enter Clementine

The first of the Lafayette ax murders was of the Andrus family. At this crime, there was another extremely freakish anomaly. The corpses of the parents were placed in a kneeling position, just as if they were praying over the bodies of their dead children.

Perhaps this grotesque display indicated some sort of religious or occult sacrificial ritual; or it may have been the handiwork of a serial killer with a macabre sense of humor who wanted to send up the widespread notion that the murders were committed by a religious cult.

Raymond Barnabet was arrested in Lafayette in spring of 1912 for the murder of the Andrus family. He was known to be a heavy drinker. He was convicted of the murder largely on the basis of the testimony of his wife, son and daughter Clementine, who was 19 at the time.

Clementine claimed that her father had entered the house on the night of the Andrus murder and asked his children to dispose of blood-soaked clothing. Son Zepherin testified that his father had asked him to retrieve his father’s pipe from the Andrus house; Zepherin declined to do so.

Both Barnabet and the murder victim Alexander Andrus had once worked together for the Southern Pacific, as coal shovelers. The two were thought to have argued.

With Raymond Barnabet’s imprisonment, a new trend of the Ax-Man saga began. As each alleged Ax-Man was imprisoned, the murders went on just as before.

Clementine, a Creole, was arrested herself on Nov. 27, 1911, for the murder of a second Lafayette family — the Randalls. The head of the family — Norbert Randall — was the brother-in-law of Alexander Andrus.

The Randalls of Lafayette were another family thought to have attended at least one Sacrifice Church service.

Police had noticed Clementine standing outside the home of the murdered Randalls, laughing loudly.

Clementine seems to have loved to talk about the murder. She told police she worked with an “ax gang” that included two black males and two other black females. After the Lake Charles murder, this testimony about a group of five killers would stoke talk of a “Human 5” gang.

Changing her original story, Clementine said she had committed both the Lafayette murders, as well as the Rayne and Crowley slayings.

The link between the murders and the Sacrifice Church grew stronger in the media and in the public imagination. During the trial, a Kentucky newspaper called the Hartford Harold reported Clementine was, in fact, the head of the Church of Sacrifice. The newspaper claimed it was Clementine’s doctrine that church members were not bound by human law and that they could become immortal by taking human life. (Of course, it’s impossible to verify at this stage of the game whether Clementine really believed such things. But the idea that Church of Sacrifice members were above the law is a recurrent one.)

Clementine testified that each of the Ax-Man murders followed a Church of Sacrifice revival, and that a “sacrificial ceremony” took place at each murder site.

The Voodoo Element

It was Clementine’s brother Zepherine who introduced the motif of voodoo into the complex case. It was reported that Zepherine told authorities that before the murders, Clementine had traveled to New Iberia to secure voodoo “candjas” — a term Elliott translates as “charms.”

Clementine testified in her trial that the Andrus family had been killed because it failed to follow a “message from God” delivered from a “voodoo doctor.” She told the jury “we weren’t afraid of being arrested [for the murders] because I carried a ‘voodoo’ which protected us from all punishment.”

Lafayette police tracked down the “hoodoo doctor” Clementine said had sold her the voodoo charms — New Iberia resident Joseph Thibodeaux — and brought him to Lafayette for an interview with Clementine. (Why Clementine called Thibodeaux a “hoodoo doctor” rather than a “voodoo doctor” is no longer known.) She seemed quite miffed at the doctor, yelling, “Yes, you said that I wouldn’t be arrested, but you see, here I am in jail.”

At least one newspaper account stated that the question of Clementine’s sanity was a factor in the trial. She laughed loudly at several times during the proceedings. At the end of the trial, she was quoted as yelling, “I am the ax-woman of the Sacrifice Sect. I killed them all — men, women and babies, and I hugged the babies to my breast. But I am not guilty of murder.”

Was The Preacher The Ax-Man?

There’s one big problem with assuming Clementine was the Ax-Man. The murders continued after she was imprisoned.

As true crime writers sometimes do, Elliott reveals that he feels he’s uncovered the culprit who committed this almost-forgotten string of gruesome crimes.

The culprit he fingers is one Lyn George Jacklin Kelly, who became a person of great interest to police after the murder of the Joe and Sarah Moore family in Villisca, Iowa, on June 10, 1912.

The crime followed the Ax-Man pattern to a T. The murderer killed a family of four living in their own house. He entered through the back door. He left the ax on the premises. He departed the scene by catching a train passing near the house.

A native of England, Kelly had been both a Methodist and Presbyterian preacher in his youth. At the time of the Moore murders, he was working as a temporary preacher in Villisca.

At the evening services on the Sunday before they were killed, the four children of Joe and Sarah Moore performed at the Presbyterian Children’s Day service. Kelly could have viewed them at his leisure.

And here too there were anomalies. Elliott cites Dr. Ed Epperly, the leading historian of the Villisca murders, as saying that at the murder scene, police found a three-pound piece of bacon wrapped in cheesecloth, leaning against a wall. Furthermore, the victim had placed gauze on the faces of all the child victims and had covered all the mirrors with bedclothes.

Kelly was fascinated with the murders from the beginning, and, when he could, accompanied police on their investigations. Eventually, he delivered a confession to local police. He said that when he killed the Moores, he saw a “shadow” that he concluded was God. He said the shadow said to him “Suffer the little children to come unto me,” then said, “Slay utterly.” After he entered the house, said Kelly, the shadow told him to “Go further; go up” — that is, go upstairs.

Kelly was already known to police as a peeping Tom who was in the habit of trying to get women to remove their clothing. In one incident, Kelly advertised for a stenographer. Any woman who applied was told she would have to work in the nude as Kelly was writing a book on “human passions.”

It’s little surprise that Epperly concludes that Kelly “was very unstable; mentally unstable and financially unstable.”

Epperly sees Kelly as the likely perpetrator of a string of ax murders of families that took place in Ohio, Indiana, Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, Iowa and Missouri between 1909 and 1913.

Elliott presents one compelling argument for seeing Kelly as the Southwest Louisiana Ax-Man. The dates of Kelly’s Midwestern murders never overlap with those of the Louisiana and Texas murders. Furthermore, the latter murders were committed during the winter months, while the Midwestern murders took place in summer months. That’s the pattern one would expect from a “snow bird” who sought warm climates during winter. Note that all the Louisiana Ax-Man murders took place between November and February.

In 1914, Kelly was sentenced to six months at St. Elizabeth’s mental hospital in Washington, D.C. After a year of probation, during which he was under intense police custody, Kelly was arrested and tried for the murder of the Moore’s. There were no more murders in the Ax-Man style after Kelly was sent to St. Elizabeth’s.

There’s a possible connection between Kelly and the Sacrifice Church. During Kelly’s 1917 trial for the Moore murders, some of the witnesses testified that Kelly had frequently preached about “blood sacrifice.”

Is there any reason to discount Kelly as the likely Ax-Man? There’s one big one. All of Kelly’s victims in the Midwest were white.

Kelly had once served as a chaplain for the New Jersey Ku Klux Klan. It’s possible that his ideology about race, coupled with whatever mental illness he had, led him to focus on blacks when he was south of the Mason-Dixon line and on whites when he was elsewhere.

‘He Was Real, You Know?’

Elliott tracked down the locations where the nearby ax murders occurred. One especially curious discovery was that of the “Blue House” on Madison Street in Lafayette, which residents think is haunted.

Sonya LaComb of the Historic Preservation Commission of Lafayette told Elliott she once talked with a now-deceased woman who had lived to an advanced age as a devoted Catholic. This woman made it her mission to minister to those on both sides of Madison, but tended to skip the 500 block, where the blue house is located.

LaComb says that the woman told her, “when I asked [other people] about the blue house, I couldn’t get anything out of anyone or anywhere with anyone. All I was able to get was that a family had vacated the blue house. No elaborations, nothing at all. And that made me wonder what was so bad about the blue house.” It’s just one more element of high strangeness in an exquisitely strange case.

Based on the blue house’s location, Elliott thinks it could have been the house of the Mrs. Guidry who once employed Clementine Barnabet as a servant. If it was, it would have been the house where police found the blood-soaked clothing that helped send Clementine to jail.

In the neighborhood of what was once the Broussard home in Lake Charles, Elliott sought out elders. He found Marian Jackson, who assured him that when she was a young girl in the 1930s, blacks in the area were still quite frightened of the Ax-Man.

Jackson invited Elliott in for a cup of coffee. Elliott ends his book with this appropriate snippet from their conversation:

“It was so long ago,” she said. “But it really happened.”

“What’s that?” I replied.

She smiled. Then she repeated.

“He was real, you know?” she said, grinning. “The Ax-Man, he was real.”

‘Curiosities’ And History

In his introduction, Elliott explains what he hoped to accomplish with his book:

“I wanted this book to be a historical collection of research; a ‘one-stop-shop’ for all of the Ax-Man’s curiosities and case details. I also sought to capture the state of fear within the communities that were unfortunate to have the cold, eldritch hand of the Ax-Man upon them.”

Elliott succeeded admirably with both objectives. The book is brimming with the sort of “curiosities” that are the delight of the true crime aficionado. Unlike mystery novels, true crime books are free to leave loose ends hanging. Elliott makes just enough conjectures about loose ends to send readers off on rich trains of thought.

But one shouldn’t assume that the book is simply a freak show. It can be read as both local and regional history. There are ample anecdotes of the family, social and governmental life of the time.

The local reading public will be on the lookout to see what curious case from the past Elliott will cast his eye on next.

Elliott will appear will appear at the Westlake branch of the Calcasieu Parish Library for a book-signing at 2 pm on Friday, March 13.

Comments are closed.