Among the musicians of my time, there were always three that — for me — were predominant in popular music: Lou Reed, Iggy Pop and David Bowie. Now one of those three has died, and his death may have been due to old age. (More on that later.)

A quick look at the comments about Lou Reed’s death on Oct. 27 shows they were full of links to the other musicians in the trio I’ve named. On Facebook, Bowie called Reed “a master.” Pop said the report of the death was “devastating news.” British singer Lloyd Cole wrote, “Without Reed, there is no Bowie as we know him. Me? [Without Reed’s influence] I’d probably be a math teacher.”

I single out Reed, Pop and Bowie because I think they did more than any other musicians of my time to give depth and substance to popular music. They worked hard to endow the popular song with the same sort of profundity and insight that such earlier figures as Stephen Foster, Billie Holliday and Cole Porter gave it.

I first learned about Reed’s work through a Velvet Underground album I found priced at $2.98 in a cut-out section. At the time, I was starting the long transition from childhood to adulthood, and hadn’t known that anyone at all wrote lyrics that described that transition with precision. I was pleasantly shocked by lyrics such as those for the 1969 song “Candy Says”:

Candy says, “I’ve come to hate my body,

“and all that it requires

“in this world.”

Candy says, “I hate the big decisions

“that cause endless revisions

“in my mind.

“I’m going to watch the bluebird fly

“over my shoulder.

“I’m going to watch it pass me by.

“Maybe when I’m older …

“What do you think I’d see

“if I could walk away from me?”

To the degree that the Velvet Underground was known in its day, it was know for lyrics about the neurotic, uneasy, oversensitive introvert: the misfit; the fish out of water; the loner and solitary. The relatively well-known song “All Tomorrow’s Parties” (1967) catalogued the feelings of a young person who feared to go to a party because she couldn’t find or afford hip clothing. Overcome by her sense of isolation, she “cries behind the door.”

Very similar was the narrator of the song “After Hours” (1969):

“Oh the people are dancing, and they’re having such fun.

“I wish it could happen to me.

“But if you closed the door,

“I’d never have to see the day again.”

In hearing these lyrics, I had exactly the same sense I had when I first read the novels of Samuel Beckett: “This guy’s like me.” Just as Bowie albums got me through high school, the Reed songs I just cited got me through my first semester of college.

Pop and Bowie wrote songs about figures such as the protagonist of “All Tomorrow’s Parties.” But they were more inclined than Reed to use metaphor. Reed’s lyrics were effective because they described the thing as it is in stark terms.

Reed wrote such lyrics long after his association with the Velvet Underground. Thirteen years after “Candy Says,” Reed wrote the song “Waves of Fear,” which includes such lines as:

“Waves of fear. Waves of fear.

“I’m too afraid to use the phone.

“I’m too afraid to put the light on.

“I’m so afraid I’ve lost control.

“I’m suffocating without a word.”

As these lyrics indicate, Reed wrote not just about isolation and alienation, but also about mental illness. And he wrote about the drugs taken by the mentally ill, and the effects of these drugs on the body.

The Velvet Underground’s best-known song was a lyrical ballad about heroin. Reed wrote songs about such topics as overdoses, habitual crime, S&M, violence, guns, prostitution and transvestitism. His notorious Berlin was a song cycle about a prostitute plagued by physical abuse, drug abuse and loss of custody who ends her life in a suicide. After three of Reed’s close friends died in a short period in the mid-1980s, he wrote Magic and Loss, which is probably the only American song cycle on the topic of death that wasn’t written by a classical composer. In its obituary of Reed, The Guardian described the matter succinctly, when it called Reed “a chronicler of life’s wilder, seamier and more desperate side.”

Of course, a person who considered himself an outsider could identify with Reed’s outsiders even if his experience was vastly different from theirs. The same was true of the characters Bowie and Pop wrote about — characters who were alienated as a result of their extremity or inability to fit in.

One other way in which Lou Reed brought substance and pertinence to popular music was by bringing experimental music into it. This aspect of Reed’s work is much better known than the Velvet Underground lyrics I quote at the beginning of this essay.

One of Reed’s colleagues in the Velvet Underground was John Cale, a Welsh classical viola player who had worked with the experimental music and performance collective Fluxus. In the early 1960s, he came to the U.S. and performed with the experimental composers John Cage and La Monte Young.

In tandem with Cale, Reed pioneered the form of music that would eventually be called “power electronics” — musique concrete, sound collage and tape manipulation created by professional musicians outside the academy.

The Velvet Underground’s “European Son” (1966) and 17-minute-long “Sister Ray” (1968) are probably the beginnings of power electronics. “Sister Ray” was recorded in a single take, with much of the music improvised. It’s said that the engineer found the music too noisy for his taste, and, leaving the Record button engaged, left the booth, telling the band, “I don’t have to listen to this. Come and get me when you’re finished.”

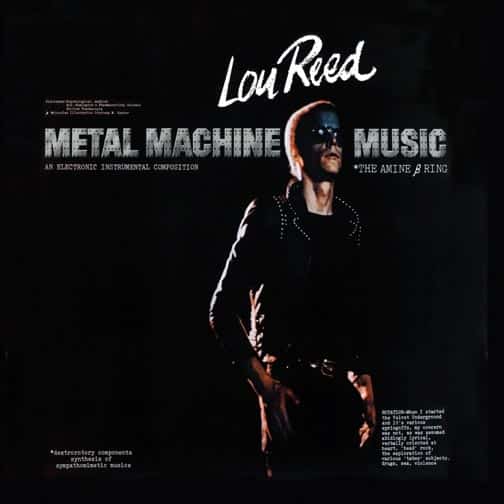

Most aficionados of power electronics feel that Reed’s 1975 double album Metal Machine Music was the first lengthy recording of power electronics. Each side of the recording had only one cut, with each cut titled Part 1, 2, 3 or 4. Each cut had a time of 16 minutes, 1 second. The recording ended with a groove that repeated the last 1.8 seconds of the music until the needle was manually removed from the record.

For the initial recording of Metal Machine Music, Reed wrote a lengthy essay that listed and described numerous instruments and electronics (such as the “amine beta ring”) that he said he had used to make the music. He later admitted that all the information in the essay was fabricated and that none of the instruments he wrote about existed.

Reed would eventually state he made Metal Machine Music by setting electric guitars at short distances from amplifiers that had been turned to such a high volume that the sounds they produced would keep the strings of the guitars vibrating. In effect, once the guitar strings had been plucked or strummed, the guitars would go on playing themselves.

Metal Machine Music was widely interpreted as career suicide. Rock critic Lester Bangs titled his review of the album “How To Succeed in Torture Without Really Trying.”

But Bangs was one of the few critics astute enough to recognize the obvious: Reed had spent a decade writing challenging music as a way of thumbing his nose at the popular music industry. While critics saw the music as a joke, Reed saw their reaction to it as farce.

Reed would continue to make obviously experimental music. He performed Metal Machine Music live in its entirety with the German experimental classical ensemble Zeitkratzer in 2002. And in 2008, he formed the Metal Machine Trio: an ensemble that played only improvised music.

My favorite form of experimental music created by Reed was one that was cited by many of his fans: the quirky twists he put in the form of the popular song.

In such early and mid-1970s albums as Sally Can’t Dance and Coney Island Baby, Reed seems to be following the traditional pop song structure, even going so far as to use the verse-verse-chorus format. But something isn’t quite as we expect it to be.

In the 1975 song “She’s My Best Friend,” for example, Reed constructs a verse not by repeating a simple melody over and over, but by creating a different, elaborate melody for each line. The melodies of both verse and chorus are more complex and less dramatic than those traditionally used in pop music. There is, for instance, no effort to create a “hook.” In many ways, the music sounds more like some obscure form of liturgical chant than the sort of thing one hears on the Billboard Top 20.

These pop songs that didn’t sound quite like pop songs pleased me to no end. To hear music that in some ways sounded familiar but in other ways sounded utterly foreign and new always made me feel as if I were entering an alternative world far more exciting and satisfying than the one I’d always inhabited. I still feel that way about these songs.

It’s a feeling that may not have been shared by Reed. Of the album Sally Can’t Dance, he complained, “The worse I write them, the better they sell.” He may have been most comfortable with the obvious and extreme experimentation of such works as “Sister Ray,” Berlin and Metal Machine Music. (He claimed that he made Berlin so that he’d have some music he could listen to.)

The last topic I want to cover in this essay is the notion that Reed died of old age. The official explanation was that Reed died from complications from a liver transplant he received earlier this year. But he was 71 when he died. Could the age have been a primary factor in his susceptibility to the complications?

There are some indications this was so. Shortly after the transplant, Reed’s wife, performance artist Laurie Anderson, told the press, “It’s as serious as it gets. He was dying. You don’t get it for fun.” A few weeks later, Reed wrote on his Web site, “I am bigger and stronger than ever.” But when he was interviewed at the Cannes Lion Festival in July, Reed said to reporters, “The other day I was 19. I could fall down and get back up. Now if I fall down, you’re talking about nine months of physical therapy.”

It also seems odd that Reed would travel to Cannes Lion if he felt liver failure were imminent.

I don’t know why the idea of a great musician dying of old age seems much sadder to me than the prospect of a young musician dying from an overdose or car wreck. The changes that come with old age are as ordinary a phenomenon as any in nature. Yet these same changes seem astonishing to anyone who experiences them, feels them deeply and thinks about them.

I don’t know whether there are ways to be really prepared for the changes of old age. If there are, being so in tune with the feelings of oneself and others that one can describe them to a T may be one of the ways.

Comments are closed.