The Catholic Cemetery Restoration Project

Story By Brad Goins ~ Photos By Kimberly Zeno

If you took a walk through the old Catholic Cemetery, you might feel that you were strolling across a wide green field of waving grass with a few clusters of graves scattered here and there.

But that’s not quite how it is. Even if you walk across a long stretch of unbroken grass in the Catholic Cemetery, your entire path cuts across the graves of area residents who were buried more than a century ago. Today, no human construction marks their resting places. But the remains are there under the surface all the same.

And that’s how it is throughout the entire square acre occupied by the Catholic Cemetery.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the supervisors of the cemetery declared the plot was full. The last occupants to be laid to rest were a father and his two young children, who had died in a berry poisoning accident and were buried together in 1915.

As is often the case with cemeteries, difficulties with maintaining the plot arose long before it was full. The first occupants of the cemetery took their places during the years of the Civil War. But by 1887, a newly arrived Father Edward Fallon found that the cemetery had become a “wild pasture,” according to one history. The Father constructed a fence around the plot and had the graves repaired.

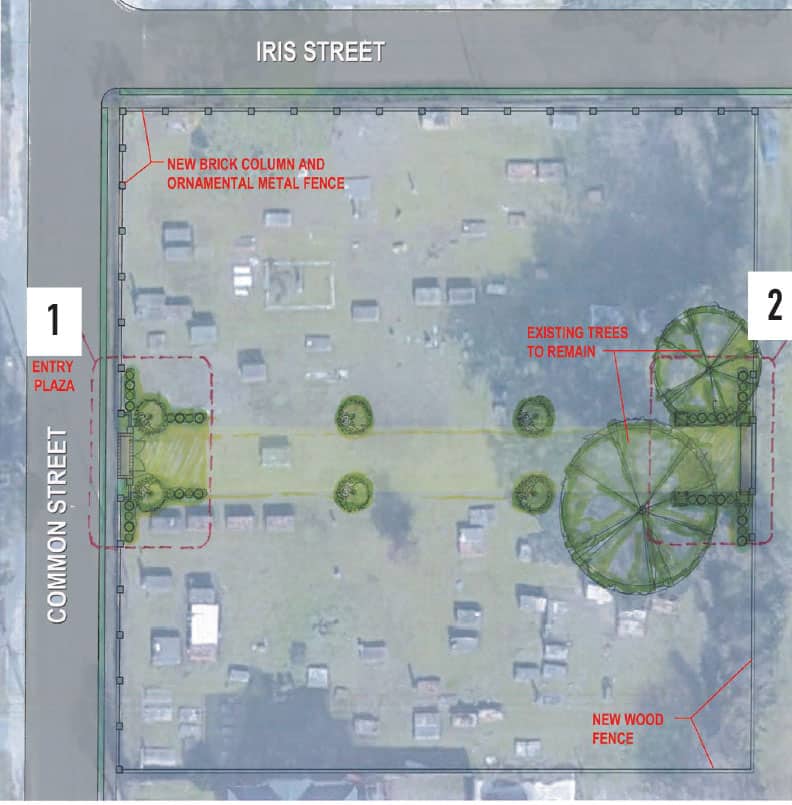

Thus began the long, sporadic work of maintenance of the cemetery located at the intersection of Common and Iris Streets.

The maintenance effort may have gotten its biggest boost when the Catholic Cemetery Restoration Project was established in June, 1997. Sue Durio was a board member then and still serves in that capacity.

As a child, Durio had experienced first hand a Catholic Cemetery that was in dire need of maintenance. “Back then,” she says, “there wasn’t an appreciation for graveyards.” She recalls that in her youth in Lake Charles, she and other youths could go to the cemetery and look into tombs that had deteriorated or been broken into and see bones.

As a child, she says, she and others felt the cemetery “was a disaster; was not maintained; was scary.”

When the maintenance project began in 1997, says Durio, there were “a lot of open and broken tombs” in the cemetery

Leaders of the restoration project immediately made a plat so that workers could at least refer to the tombs that were still in place (even if they were in poor condition). The project got a break when a judge assigned a mason to do community service in the graveyard.

Today, the graveyard looks quite a bit different than it did when I first saw it on my arrival in the city in 1999. At that time, some of the above-ground graves had lost many of their red bricks due to the decay of the mortar. And the lids on top of some of these tombs were shattered, so that one could indeed see what was inside.

Today, these problems have been resolved. Red brick tombs now have a full complement of brick. “We don’t have anything exposing anything” at present, says Virginia Webb, a long-time board member and the wife of group leader Patrick Webb.

Airborne Bones

From its inception, one of the biggest obstacles to steady maintenance of the graveyard has been repeated damage inflicted by heavy storms.

One stormy night, Patrick Webb got a call. A large water oak in the cemetery had been ripped out of the ground by a strong wind. In its root ball were human remains and pieces of casket. When the tree fell, says Webb, the bones “went airborne,” landing in a semicircle around the fallen tree.

A trained volunteer arrived on the scene in 15 minutes. Using rubber gloves, he collected the bones. They will remain at the Johnson Funeral Home until a reasonable plan for their ultimate internment can be formulated.

A Startling Discovery

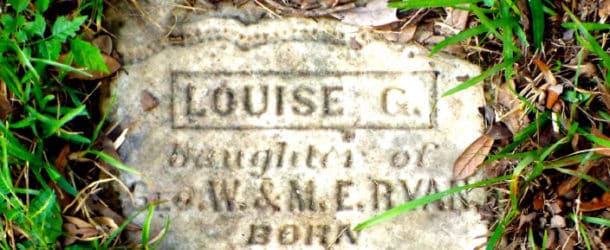

Workers in the restoration project have other curious stories to tell. In 2014, volunteer Giney Davis Fontenot showed up one day to help clean graves. But she had another motive for being in the cemetery. She believed her Aunt Loraine V. Davis had been buried in the cemetery and hoped to find her tomb or some indication of it.

Fontenot began working on a long, flat grave that had become covered with vines. “She was drawn to the grave,” says Patrick Webb. As she removed the vines, she was able to make out a name: Loraine V. Davis. “This is the grave I was looking for,” she called out to the other workers.

The odds against someone finding any given grave intact are probably quite high. Fragments of broken tombstones are collected all over the graveyard grounds. Trained volunteers are gradually piecing together parts of the tombstones: “putting [them] together like a jigsaw puzzle,” in Virginia Webb’s words.

In the course of this process, they’ve found 52 names that weren’t on their original lists of people who were buried in the cemetery. But one big problem remains; they “don’t know where [the tombstones] go.”

Early Challenges

In 1861, William Hutchins purchased an acre of land near downtown Lake Charles and had it established as the site of the Catholic Cemetery. Hutchins may have established the grounds as an alternative to Corporation Cemetery, which was considered a graveyard for Protestants. Three years later, Hutchins was buried on the grounds.

Hutchins’s case is an instance of what one often sees demonstrated by the markers in the cemetery — the high frequency of childhood death in decades past. Of Hutchin’s and his wife’s six children, only two lived to adulthood. Marie died at 7 of scarlet fever; Stewart died at 5 of kidney trouble and Alexander died at 18 months of whooping cough. A child who died at birth was called only “Infant.”

Maintenance problems inevitably affect what we know about the dead. It is thought that 10 LeBleus were buried in the cemetery. But five of their headstones were either broken or temporarily removed. No obituaries were ever published for three of the names. At present, it is only known where five of the 10 LeBleus are buried. The remainder lie peacefully under patches of unbroken grass.

At its inception, the cemetery was associated with the St. Francis La Salle Church, which burned down in the Fire of 1910. There’s some debate as to what happened to the Catholic Cemetery records during the fire. One story goes that the records were carried to the cemetery for safe keeping, but an ember found its way to them nonetheless.

Whatever the explanation, when the Fire of 1910 was extinguished, all comprehensive records of who was buried where in the cemetery were gone for good.

The Hurricane of 1918 took its own severe toll on the cemetery. Cypress crosses had been used for many of the graves. These were all uprooted by the hurricane winds, making it all the more difficult to determine who was buried and where the remains were.

Two surveys, the last made in 1957, resulted in lists of names on tombstones that could still be read.

With many of the shattered tombstones reassembled, the restoration project now places the number of those buried in the cemetery at some figure slightly above 300.

Today, the grounds contain a mix of Louisiana’s distinctive above-ground tombs and the underground tombs that are prevalent in areas far from the coast. Cynthia Webb thinks that right now, there are, perhaps, 50 fully intact graves remaining in the cemetery.

Difficulties Of Maintenance

We’ve looked at a few of the major challenges to maintaining the Catholic Cemetery. Now let’s look at a few more.

First, there’s a difficulty with resources. There is no running water or electricity at the site.

And there are bigger problems. Even after the restoration project began, the crew noticed, from time to time, that some vandal had entered the grounds and broken a tombstone. “People have some perverse pleasure in going in and breaking things,” says Patrick Webb.

Theft is always a concern. At one point, the preservation group had decided to incorporate an image of a gate to a particular grave in a logo for the project. Before the logo could be completed, the gate had disappeared. Some thief had likely taken the wrought iron structure in hopes of selling it.

It can be daunting to restore old materials in such a way that they aren’t harmed. The materials in the Catholic Cemetery are all more than a century old. When repairs are made, materials consistent with those used at the time must be employed.

For example, the red bricks used in the above-ground tombs are considerably softer than today’s bricks. Thus, a lime-based mortar must be used to repair them. Contemporary concrete and cement products will degrade the soft bricks. “Portland cement is really bad,” says Durio.

Increasing Awareness

Now that restoration has gone on for some time, the group is focusing on increasing local awareness of the cemetery. Even residents who’ve lived here a long time may not know where the cemetery is. If they do, they may not know of its special status as a Catholic Cemetery. “A lot of people don’t have a clue what this cemetery is about,” says Patrick Webb.

Cynthia says the Catholic Cemetery is “historically important as well as being a sacred spot.” The challenge is to make residents aware of these attributes.

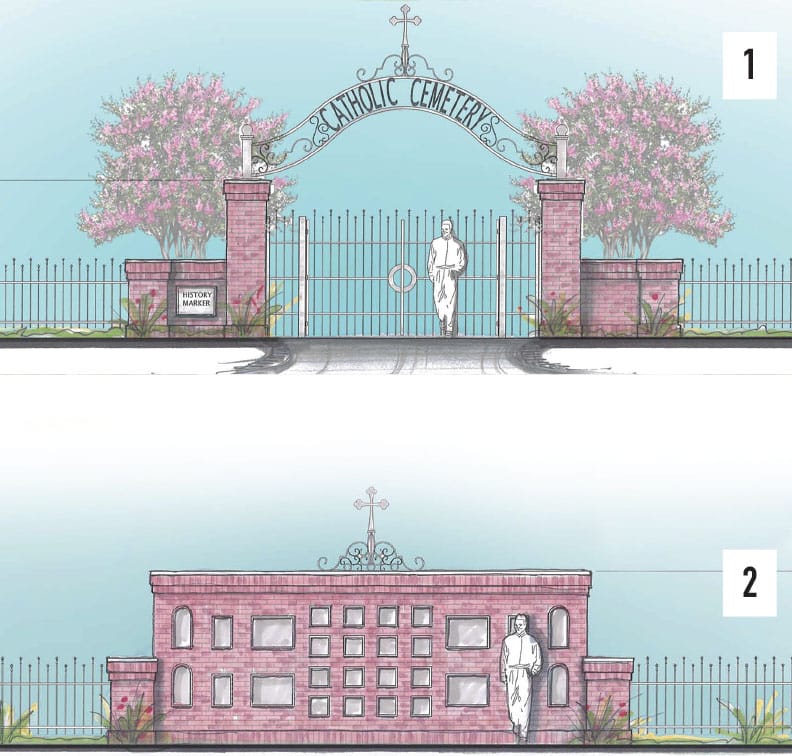

“It’s a very opportune time because we’ve ended up with a plan to put in an ornamental gate,” says Patrick Webb. An arch over the gate will bear the words CATHOLIC CEMETERY in large capital letters. This will certainly “raise the visibility of [the graveyard].”

Because it is impossible to know where most of the reassembled gravestones belong, they will be placed in a Remembrance Wall that is also to be added.

The total cost of the project is estimated to be $150,000. It will include such additions as security lights to keep down vandalism. The restoration group will announce plans for a major fundraiser for the project soon.

If you want to participate in a clean-up of Catholic Cemetery, you’ll have a chance between 9 am and noon on Oct. 20. It’s suggested that participants bring water, work gloves, a hat and mosquito repellent.

The Catholic Cemetery will be one of the cemeteries participating in the Living Cemetery Tour on Oct. 26 from 5-8:30 pm. Participants will be directed to the graves of three historical figures, whose stories will be told by actors in historical costume. I don’t know which three figures will be chosen. The cemetery is the final resting place for many historical figures, including Pujos, LeJeunes and Reids. For information about the tour, call 375-7373.

Those who are interested in contributing to the restoration project or the $150,000 improvements project are invited to contact Reverend Rommel Tolentino, the Pastor of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Lake Charles. The Catholic Cemetery Restoration Project is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

Comments are closed.