Death By Drugs: The Opioid Crisis In SWLA

A Lagniappe Magazine Roundtable

NOTE FROM DR. MICHAEL KURTH

From left: John DeRosier, Gary Sonnier, Burt Hooper, Dr. Terry Welke, Glynn Wheeler, Dr. Michael Kurth.

This feature is the second of my three-part series on the opioid crisis. In the first part, I described the crisis from a national perspective (column available at bestofswla.com); in this article, I look at the drug market in Southwest Louisiana.

I put together a roundtable discussion with five persons knowledgeable about the situation: District Attorney John DeRosier; Gary Sonnier, director of the Combined Anti-Narcotics Task force (C.A.T.); Burt Hooper, the Assistant Director of the C.A.T.; Calcasieu Parish coroner Dr. Terry Welke; and Glynn Wheeler, a reformed addict and drug dealer who now runs the Hope House in DeQuincy for addicts trying to rebuild their lives. Lagniappe associate editor Karla Wall was also present at this importnat roundtable discussion.

Michael Kurth: We’ve see an alarming increase in deaths due to drug overdoses nationwide. Is the same thing happening in Southwest Louisiana?

Terry Welke: Unfortunately, yes. Since January, my office has recorded 23 deaths from drug overdoses.

Michael Kurth: So, on an annual basis, we may be looking at 35 drug deaths. How does that compare to earlier years?

Terry Welke: The worst time for drug deaths was in 2006 and 2007, when we had people going to Texas “pill mills” — medical clinics just across the border that were dispensing Xanax, Soma, and Hydrocodone by the bushel basket. In 2006, there were 51 overdose deaths, and in 2007 it was 56. Then Mr. DeRosier went to the Texas legislature and got them to shut down those “clinics” and our overdose deaths dropped to around 20 a year.

John DeRosier: I am very proud of that; it made a big difference.

Glynn Wheeler: He also said back then that he was going to charge drug dealers with murder if the drugs they sold resulted in someone’s death. It scared me into moving to Texas.

Michael Kurth: We’ll come back to that later, Glynn. Are the drugs that are killing people today different from the drugs in 2006-07?

Terry Welke: Yes; of the 23 deaths this year, 10 were due to methamphetamines, three involved fentanyl and 10 involved heroin — six of those were in just the past month.

Gary Sonnier: Last year, there was a death from Carfentanil, so we know it is on the street as well. Carfentanil is 100 times more potent than fentanyl; it’s called the “elephant drug” because its legitimate use is to tranquilize large animals.

Michael Kurth: How do the drug deaths break down in terms of demographics?

Terry Welke: 12 were males between the age of 19 and 56, and 11 were females between the age of 35 and 56. In terms of race, 3 were black and 20 white. Geographically, I didn’t see a pattern: they are all over the place — rural, urban, suburban. These drugs are everywhere.

Michael Kurth: We’ve been talking about drug deaths, but what about drug overdoses? We recently had 45 overdoses in just two days in Lake Charles.

Terry Welke: The coroner’s office only deals with drug deaths; you would have to contact the hospital administrators for data on overdoses. And there may be privacy issues regarding medical records.

Michael Kurth: Are drug deaths a good metric for measuring the extent of drug abuse?

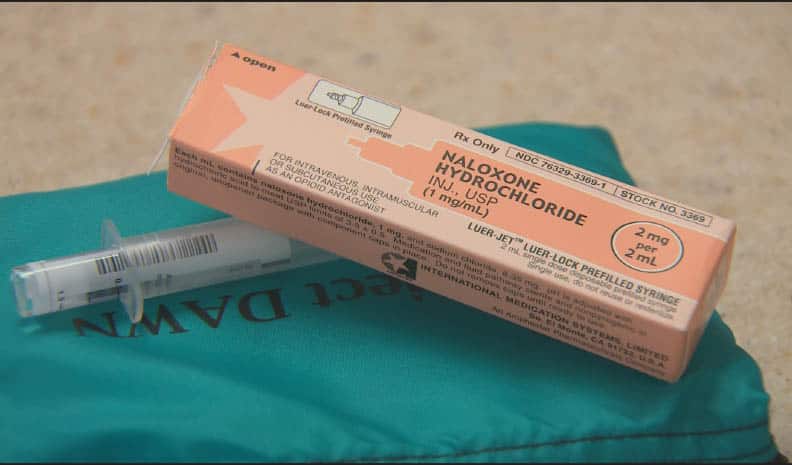

Gary Sonnier: It’s hard to tell. Hospitals have gotten better at treating overdoses. They didn’t have Narcan back in 2006-07. Now hospitals have it; first responders have it; even the dealers and addicts have it. So it’s quite likely drug use is increasing much faster than drug deaths indicate.

Terry Welke: I think we are going to see more drug deaths even with Narcan. Heroin is now being cut with fentanyl to make it cheaper and more potent. And it takes more Narcan to revive someone when fentanyl and other chemicals are involved.

Michael Kurth: How much of the crime in Calcasieu Parish — burglaries, assaults, impaired driving, all the way up to homicide — is associated with drugs?

Gary Sonnier: I’d say 75-80 percent. (The others at the table all agreed with that estimate.)

Michael Kurth: You said the opioids in 2006 and 2007 were coming from “pill mills” in Texas; where is this new stuff coming from?

Gary Sonnier: The southern border: it comes up from Mexico to Houston and Dallas, and it’s distributed east from there.

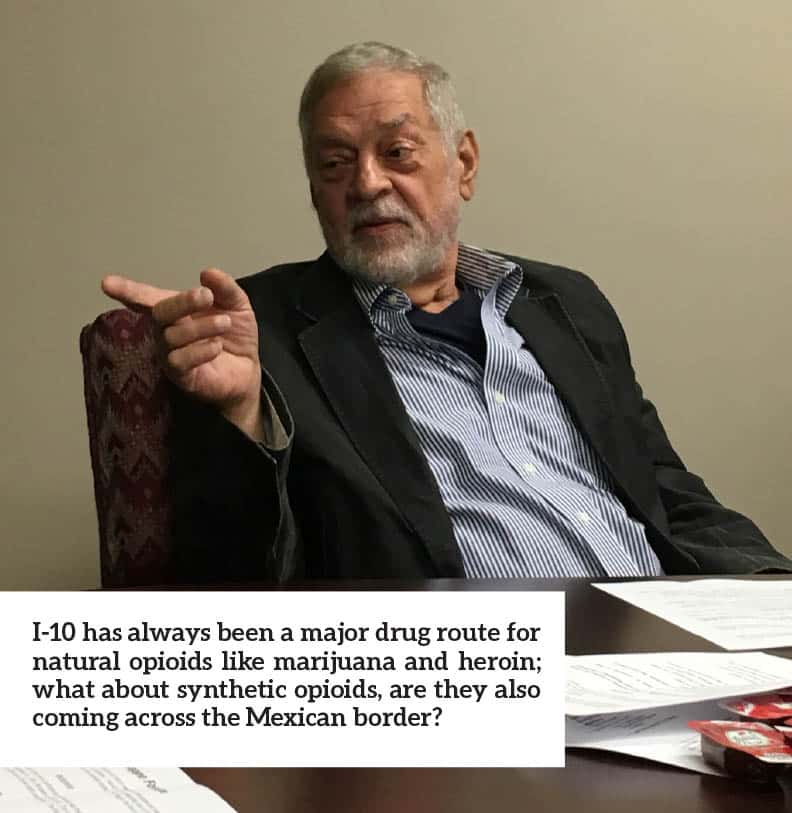

Michael Kurth: I-10 has always been a major drug route for natural opioids like marijuana and heroin; what about synthetic opioids, are they also coming across the Mexican border?

John DeRosier: “Synthetic marijuana” is a misnomer. It’s not marijuana, it’s just crushed herbs and leaves, so it’s legal. Then distributors spray it with chemicals that may also be legal, but are not intended for human ingestion.

Terry Welke: An overdose from synthetic marijuana can be hard to treat because you don’t know what chemicals you are dealing with.

John DeRosier: A lot of the chemicals like fentanyl are made in pharmaceutical factories in the Far East and China, then smuggled across our southern border.

Burt Hooper: A lot of the stuff is also sent through the mail or by FedEx or UPS. It can also be ordered off the “dark web.”

Michael Kurth: Is there any indication these drugs are associated with the temporary workers who are here due to our industrial boom?

Gary Sonnier: We’ve seen no indication of that. (They all agreed.) I think we would have this problem even without the temporary workers. I’ve traveled all around the country with the drug task force; it’s the same everywhere. They are inundated with meth, synthetic marijuana and heroin laced with fentanyl.

John DeRosier: It’s especially bad in small town America. I grew up in a small town, and we never heard of drugs back in the ‘60s; now you can buy heroin on just about any street corner.

Gary Sonnier: In small communities outside Calcasieu Parish, they don’t have the law enforcement resources we have.

Burt Hooper: Drug dealers have virtually taken over some small towns.

Michael Kurth: I’ve read that the drug problem is especially bad in rural America. One theory is that in places like West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Kentucky and in our inner cities, people don’t have jobs, so they turn to drugs out of desperation. But the evidence suggests the current wave of drug addiction began in more prosperous communities where people had access to hospitals and medical clinics that were passing out opioids like M&Ms on Halloween, and it spread to the rural areas. If you overdose in a city, your “friends” can dump you off at a hospital where they’ll give you some Narcan; if you overdose in a rural area, you’re just going to die in your own vomit. If it’s desperation and lack of jobs, why do we have this problem in Calcasieu Parish when we have one of the strongest economies in the nation and 15,000 temporary workers?

Burt Hooper: People have more money now.

Michael Kurth: Are there drug problems among the plant employees?

Terry Welke: We send test samples for synthetic marijuana to a lab. That is generally not part of employee screening; it’s something that might be done after a problem has developed like an accident or something.

Glynn Wheeler: We are now seeing second- and third-generation drug users. The parents — one or both of them — are drug users and the whole family becomes infested with drugs. It’s not an excuse, but that is how my life with drugs began.

John DeRosier: That problem is more prevalent than most people realize. The first generation may have simply smoked pot back in the ‘60s. In that drug culture, it’s easy to graduate to “the-drug-of-the-day.” Now it’s heroin and fentanyl because it’s cheap and gives them a more intense high.

Terry Welke: During World War II, they gave wounded soldiers morphine; same thing in Vietnam. It took away the pain and gave them a feeling of euphoria. But the body builds up a tolerance to drugs fairly quickly, so they needed more and more drugs to achieve that high.

Burt Hooper: They call it “chasing the high.”

Terry Welke: I’ve seen people go through rehab and get clean. But when they get back with their old buddies and start using the same amount of drugs as before, their body can’t tolerate it and they overdose.

Michael Kurth: What puzzles me is how one goes from using prescription opioids to using heroin laced with fentanyl. I always thought of these as distinct markets. Like, powdered cocaine was what rich people used; opioids were used by veterans and despondent suburban housewives; crack cocaine and heroin were sold on inner city street corners.

Burt Hooper: That era has passed. Cell phones have eliminated the street-corner drug dealers. If you’re an addict, you just call your dealer on his cell phone and arrange to meet in a parking lot somewhere. The dealers don’t fight over street-corner turf any more: it’s a business and they market their drugs through social media.

Gary Sonnier: The dealer just pulls up in their car next to you, door-to-door: methamphetamines, heroine, pills … bam, bam. The whole deal takes 15 seconds and they’re gone. It’s that fast. It makes it really hard to catch them in the act of selling drugs.

Michael Kurth: How can law enforcement disrupt this market?

Gary Sonnier: It’s a challenge, but our local law enforcement agencies are working well together. Mr. DeRosier and the CPSO (Calcasieu Parish Sheriff’s Office) are doing everything they can, and the courts have a number of programs that offer alternatives to jail for drug offenders.

John DeRosier: It takes a combination of efforts: law enforcement has to get the bad guys off the streets. But to get to the underlying problem, you also have to address the demand for drugs. Unfortunately, we are not getting the cooperation we need from the state. Two years ago, I went to our legislators and told them we needed to increase the penalties for distribution of heroin if it contains fentanyl. That bill passed in the house 81-6. But the caucus from New Orleans and Baton Rouge opposed it and it died in a senate committee. At the time, fentanyl wasn’t in Louisiana, but it is now. So maybe things will change.

Michael Kurth: Is there a tip-line the public can call to report drug activity?

Burt Hooper: Yes, they can call 431-8001. It’s completely anonymous.

Michael Kurth: Glynn mentioned earlier [the practice of] treating drug overdose deaths as murder and going after the people who sold [the users] the drug.

John DeRosier: We can do that; in Alexandria, they charged a dealer with murder last year. But in most cases it’s very hard to prove beyond a reasonable doubt where the drugs came from that caused a person’s death.

Michael Kurth: But can tougher laws solve the drug problem? Or do they just treat the symptoms and not the disease?

Glynn Wheeler: A true addict may have a drug of choice. But if they can’t get that drug, well, they’ll take whatever you got. They’ll do anything to feed their craving.

John DeRosier: I believe strongly in specialty courts. Among the people who go through our specialty courts — drug court, DWI court, mental health court, and veterans treatment court — the recidivism rate is less than half of those who go through probation and parole. We need more of these courts. But again, I am having trouble getting the state and some legislators on board.

Update: The day after this roundtable, a federal grand jury indicted nine people — five from Calcasieu Parish, one from Beauregard Parish, and four Cuban illegal immigrants — on more than a dozen counts of distributing methamphetamine and cocaine. More than $60,000 in cash and hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of vehicles were seized. It was the culmination of a year-long investigation called “Operation Cuban Ice.”

The third part of my series on the opioid crisis will look at drug addiction as a disease and the resources available in Southwest Louisiana for addicts who want to change their lives.

Comments are closed.