By Michael Kurth

A lot of people in this area avoid crossing the I-10 Bridge because of rumors it is in great disrepair and unsafe. (It has a sufficiency rating of just 6.6 percent). Thus, these drivers were befuddled when they heard that the Louisiana Dept. of Transportation and Development (La DOTD) was undertaking a $30-million, three-year project to repair the I-210 Bridge.

Wait, the 210 Bridge? That was supposed to be our “safe” bridge.

I know nothing about the structural soundness of either bridge, but I do know a bit about how the I-210 Bridge repair project might affect Calcasieu Parish. And the real cost is going to be a lot more than $30 million.

Two months ago, I was asked by the Economic Development Alliance to do a study of how the proposed closure of two traffic lanes on the I-210 Bridge would affect traffic flow in the area and the cost this would impose on local residents, business and industry and state and local government tax revenue. Here is what I found.

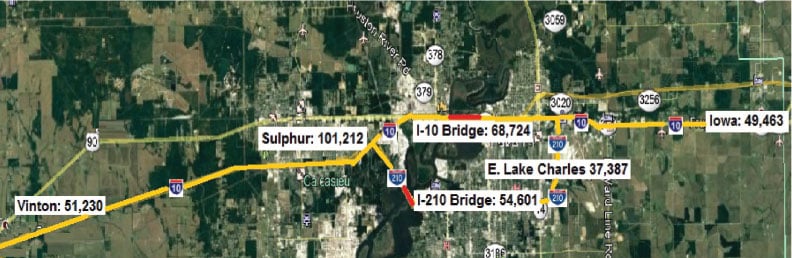

The above map shows the flow of traffic along I-10 and I-210 measured in average vehicles per day based on traffic counts taken by the La DOTD in 2016. I interpret that data as showing that 40,000 vehicles a day pass through Lake Charles on I-10 on their way to someplace else — this is pretty consistent all along I-10 — with another 10,000 vehicles either beginning or ending their travel in Lake Charles.

Along the Sulphur industrial corridor, these vehicles are joined twice a day by 25,000 local vehicles transporting people back and forth to work or taking them to Lake Charles to shop or conduct business. The pass-through traffic on I-10 continues across the I-10 Bridge, along with 28,000 local vehicles that travel back and forth across that structure.

And twice a day, 25,000 vehicles — mostly local — travel back and forth cross the I-210 Bridge. This I-210 traffic continues for 10 miles along the I-210 business corridor before tapering off as I-210 rejoins I-10.

A recent traffic impact study for the Lake Charles MPO (IMCAL) estimated that closing two traffic lanes on the I-210 Bridge would add just two to three minutes to the time it takes to travel from McNeese State University to Sulphur. I doubt that. The MPO study was based on the 2016 traffic counts plus employment information from 2013. But over the past three years, Lake Charles has been one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the nation: construction employment is now 23,900 (an increase of 214 percent); manufacturing and transportation employment is 28,800 (up 100 percent) and total employment is 113,022 (up 29 percent). Pass-through traffic probably hasn’t changed much, but residents can tell you there’s been a significant increase in our local traffic — especially the commuters who now must leave home 15 minutes or more earlier to get to work on time.

To conceptualize how closing two lanes on the I-210 Bridge will affect rush hour, imagine a grocery store with four cash registers. There are three customers in line at each register. It takes the cashier two minutes to process each customer, so the last customer in line must wait six minutes to get through the line.

Then the manager decides to close one register and move those customers to the three remaining lines. There are now four customers in each line, and the last one must wait eight minutes to get through the line — an increase of 33.3 percent in the average wait time.

It works the same way for traffic lanes. There are 12,000 petrochemical employees and 15,000 construction workers in Calcasieu Parish who cross the bridges twice a day. They currently do so in four traffic lanes; their average wage is $30 an hour and their average waiting time is 15 minutes. Thus, the value of the time they spend waiting in line twice a day is $75 a week or $3,900 a year.

If there are 27,000 commuters, this comes to $105 million a year. And closing one of the four traffic lanes each way would increase that cost by approximately $35 million a year.

But it isn’t just commuters who are affected by the traffic congestion; there are parents taking their kids to school, college students trying to get to their classes, patients trying to get to their medical appointments … they all get caught up in spillover traffic.

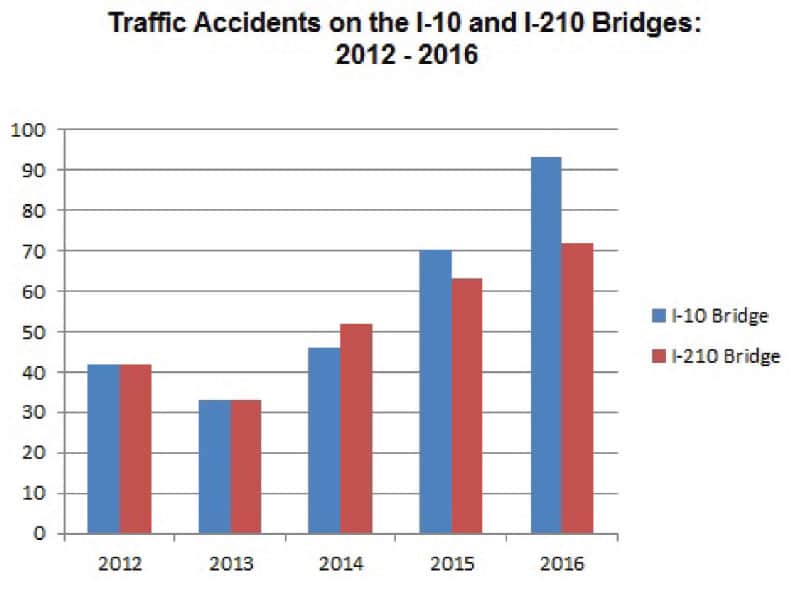

The biggest problem, however, is not the predictable traffic delays, such as those of rush hour, but the unanticipated delays caused by things such as traffic accidents, vehicle breakdowns and flat tires. The above graph shows the number of traffic accidents and breakdowns reported by police on the I-10 and I-210 bridges from 2012 through 2016. Reported incidents on the I-10 Bridge were up nearly 200 percent from 2013 to 2016, with little increase in the traffic counts during that period. Incidents on the I-210 Bridge more than doubled.

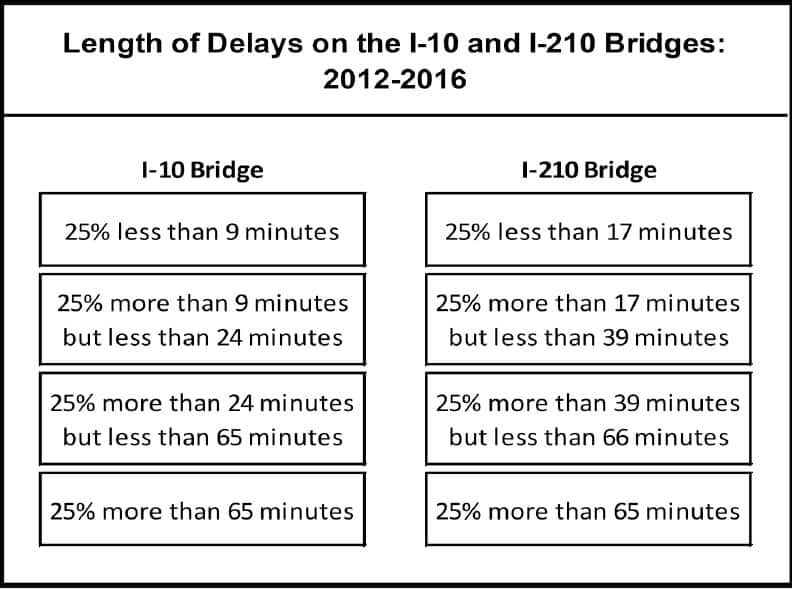

The time it took for police to restore the traffic flow is shown in the table below. Some of these incidents were relatively minor events, but 25 percent of the time, it took police more than an hour to reopen the traffic lanes and restore the traffic flow. Such incidents may not have been a big deal if they happened at 2 am; but if they happened during rush hour — as I suspect most of them did — traffic would have been backed up for miles on the Interstate.

Why are we seeing an increase in such incidents and how will this be affected by lane closures on the I-210 Bridge? Those are the big questions. It is well established that traffic accidents increase with traffic congestion, lane mergers, stop-and-go bumper-to-bumper traffic, driver “road rage” and distractions, such as cell phone use. The La DOTD says it will make use of moveable barriers, message signs synced with traffic flow, the ability to enact contraflow if necessary, and a strong Motorist Assistance Patrol presence to minimize the effects of these unanticipated events. But accidents and breakdowns are going to occur, and possibly more frequently.

The crux of the problem is that there is no alternative route for the 140,000 vehicles (and currently more like 170,000 vehicles) traveling on I-10 each day other than to cross either the I-10 Bridge or the I-210 Bridge. You can’t re-route the traffic south, because the only way to cross the Calcasieu Ship Channel is the ferry in Cameron, which can take about 10 cars at a time.

The MPO Traffic Impact Study talked about re-routing I-10 traffic to Highway 378 that goes through Westlake and Moss Bluff, but that is simply unrealistic. The only way to go from Westlake to Moss Bluff is across a two-lane drawbridge (above) that is already crowded with bumper-to-bumper traffic during rush hour.

The study also suggested sending I-10 traffic up Highway 27 to Highway 12 in DeQuincy. But that would cause massive gridlock in Sulphur, where residents are already barricading their neighborhoods to through traffic.

I hate to be pessimistic, but when I was in the Army we had a saying that you “hope for the best, and prepare for the worst.” What is the worst that could happen during the I-210 Bridge repair project? One is simultaneous events that shut down traffic on both the I-10 and I-210 bridges during rush hour. Nearly as bad, and more probable, is an event that shuts down the I-10 Bridge during rush hour, leaving just two lanes on the I-210 Bridge to handle 140,000 cars and trucks. Another bad scenario would be a major incident at one of the petrochemical plants or refineries, because most of our medical facilities are located on the east side of the I-10 Bridge.

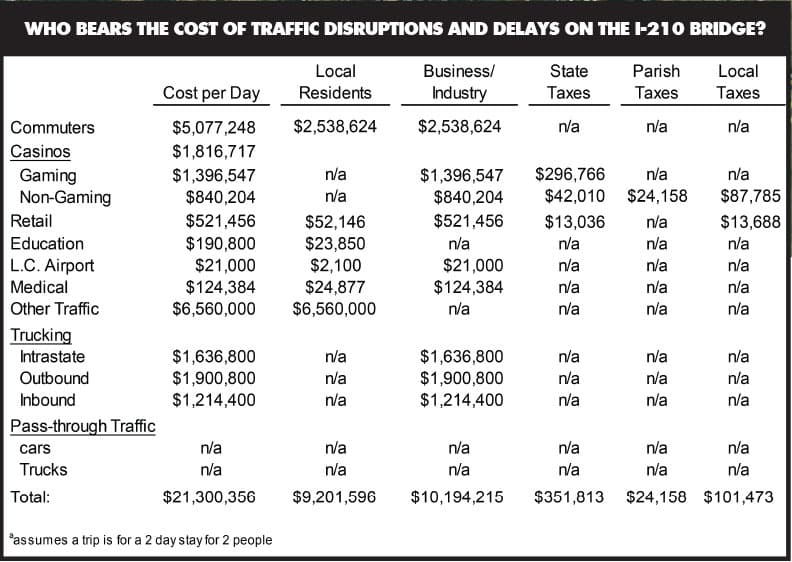

In my study, I estimate that a one-hour traffic delay on Interstate 10 costs residents, business and industry and state and local government approximately one million dollars. But this cost increases exponentially with the duration of the delay, as more and more activities are impacted. The estimated cost per day (essentially 7 am to 7 pm) is more than $20 million.

And this is not the worst of it. If these unanticipated events occur frequently enough that people begin to anticipate them, Houstonians may stop traveling to our casinos; new plants will not consider locating in the area; residents in west Calcasieu will begin traveling to Texas to shop and meet their medical needs.

Initiatives to reduce the negative impact of the I-210 Bridge repair project have focused on reducing the length of the project. The La DOTD has cut the length of the project from 3 years to around 18 months. And an incentive package for the contractor to finish the project even sooner is being discussed by local governments and affected businesses. This is all good, but safety should not be sacrificed for speed. The greatest cost by far is likely to come from unanticipated disruptions, such as accidents and breakdowns, and every effort should be made to minimize these.

One proposal of concern to me is the re-routing of truck traffic from the I-210 bridge to the I-10 Bridge during the repair project. The I-10 Bridge is a notorious problem spot for truckers: it has the steepest grade on Interstate 10, which means trucks must maintain their speed to get over the crest of the bridge while cars cut in front of them or pass them, requiring truckers to apply their brakes frequently. We saw earlier this year what happened when minor repairs were made to the I-10 Bridge; it wasn’t pretty.

There’s a cut-off from I-10 to Highway 12 near Vidor, Texas, that runs through Starks and DeQuincy over to Highway 171. This is the route many truckers took during the Sabine River flooding. Perhaps the La DOTD should consider re-routing trucks this way instead of sending them over the I-10 Bridge.

But the real lesson to be learned from this is the need for long-term planning. When we knew six years ago we were going to experience an industrial expansion of epic proportions, we should have begun at that point to plan for our infrastructure needs. Much of this problem is endemic to Louisiana politics: most of Louisiana is clamoring for funds to save industries of the past, while in Southwest Louisiana we need funding to build the foundation for our industries of the future. How can you ask those who are suffering to finance projects for those who are prospering? But that is what progress requires.

Comments are closed.