Justin Morris Visits With Yellowfin Vodka Creator Jamison Trouth

Story by Justin Morris • Photos by Lindsey Janies

While I have long been one to enjoy a tipple of some fine distilled spirits, one thing that has always been true is that I do not, or have I ever liked, the boring, soulless drab dram that is vodka. Not that I haven’t drunk vodka; I certainly have. But left with just about any other option when I’m purchasing a bottle for myself, vodka’s easily been last place on my list of options. I might even go so far as to say that in my younger and far more judgmental days, I would have looked at a vodka lover with scorn as a classless heathen: one who clearly couldn’t appreciate what the spirits world had to offer, or one who wanted to get drunk without tasting anything that resembles booze in the slightest. While those criticisms have faded away over the years, I still don’t like vodka.

That does put me in a minority amongst imbibers, though, as the colorless, and essentially odorless and flavorless, quaff of Russian roots has spread across the globe not only to become the most consumed spirit domestically, but also the most consumed distillate worldwide — and by no narrow margin, beating out it’s closest competitor (my beloved rum) by a factor of three.

Some statistics have estimated that the average Russian consumes somewhere between 13 and 14 liters of the stuff annually.

But popularity has never been my game, certainly among the things I consume and indulge in. So vodka can stay right where it’s been in my world: in its bottle, on someone else’s shelf far, far away from my lips …

So why, then, do I sit here typing these words with a room temperature brandy snifter of the stuff in hand? Why do I sip this eternally offending spirit while I have some of that sweet, delicious imported rum idly taking up space on my kitchen counter? Why do I find myself pouring more of this antiseptic, lifeless swill when I find my glass empty every so often?

Because I am drinking anything but your typical vodka.

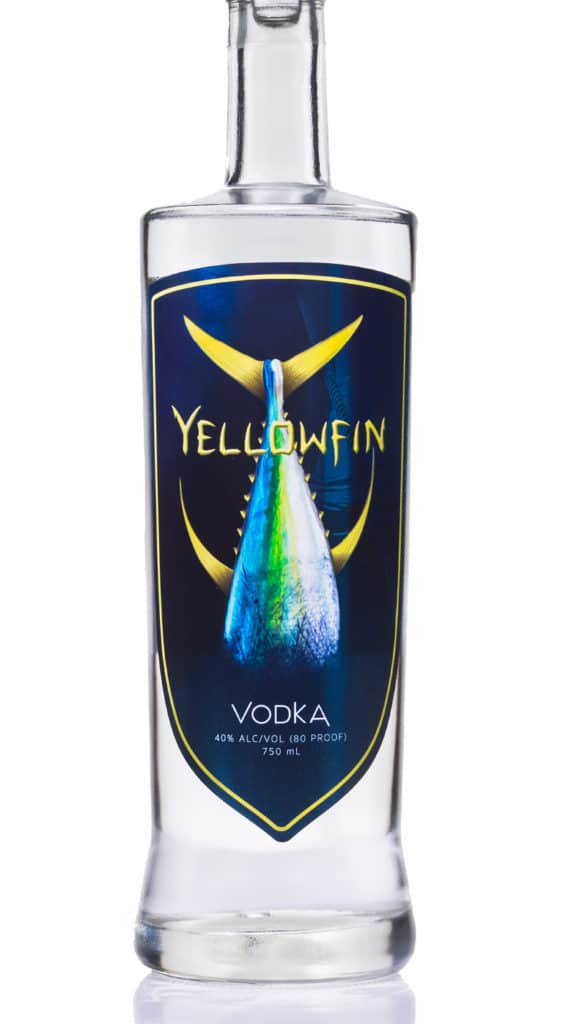

I’m drinking Yellowfin Vodka — one of the latest offerings in the rising trend of craft vodkas. It’s different, unique and iconoclastic in more than one way.

To begin with, it’s made from sugar instead of the traditional grain or potato. It’s crafted from the ground up using non-gmo ingredients as opposed to the homogeneous pre-distilled base of most vodkas on the market. And the production, from the sugar to the finished distilled product itself, all happens right here in South Louisiana.

Sulphur native Jamison Trouth was one of the aforementioned heathens who swilled away his college days mixing vodka with whatever mixer was readily available. Fortunately, he didn’t swill too much to keep him from his studies, and he eventually found himself with a chemical engineering degree, doing what one would expect any such McNeese State Graduate to do: heading to the refineries to put that education to productive, adult-level industrial use.

It wasn’t long, though, until Trouth found his personal and professional interests shifting and merging in a way that would lead him to put his livelihood on the line to chase a new boozy dream.

As in all things, should you want to know more, you are best served by going to the source. So I did just that. The Yellowfin Distillery sits on the corner of Sulphur’s East Burton Street and Highway 27. It’s pretty unassuming on the surface. It’s a simple and small metal building that sits behind a gravel parking lot set behind a metal gate one would expect to be sitting over a cow catcher in front of an expansive rural pasture. The scene is offset by a large, colorful banner featuring half of a giant brightly colored tuna touting the name “Yellowfin Vodka,” and a dark, ornate wooden door that looked somewhat out of place on a building that, at a glance, would appear to be a small fabrication shop or the large private garage of a gear head.

Just past said door, I found a small room bathed in blue with the Yellowfin Vodka iconography adorning the shelves and the walls. There was a bar that was neatly topped with bottles of Yellowfin and various mixers, including Bloody Mary mix, tonic water, club soda and ginger beer, as well as a small brandy snifter bearing an etched Yellowfin logo. Also in the room was a high-top table and two chairs, one of which was occupied by Trouth, who welcomed me to his distillery with a quiet pride that was both disarming and quite welcoming.

To start things off, he offered me a sample of his wares and served it up just as you would the namesake spirit of the snifter itself: neat. Not chilled. Not mixed. Not shaken or stirred. Just room temperature, straight out of the bottle into the brandy glass. In proper form, I took the vessel with its short stem between my ring and middle fingers, cupping my upturned palm around the bulbous bottom of the glass, giving the vodka a swirl long enough to allow the heat of my hand to reach the clear liquid.

A lift to the nose was the first sign that this was not a typical vodka. The expected rubbing alcohol smell was replaced with a subtle and delicate sweet note. A lift to the lips gave me the notion that either I had misjudged this whole vodka thing all these years or that I was waiting for a hidden camera crew to jump out and surprise me. With no signs of a Candid Camera crew, I figured it was time to sit down and find out just what was going on here …

Jamison Trouth: It really started my senior year at McNeese. I attended from 2002-07, and I studied chemical engineering. I interned for a year, so that kind of set me back. As I got closer to graduation and saw what [refinery work] was like through my internship, I realized that I wanted to do something out of the box or something different than the normal chemical engineering path.

While in school, I had a class on distillation, which ended up being one of my favorite classes. I just really liked that material. It was different and new, and I thought it was cool. Spirits were what I drank all though college. I was never a beer guy. I felt kind of left out because all the guys were drinking all the dark beers, but it just wasn’t me.

So I found that my spirit was vodka, so it started somewhere in there.

Most of what you do as a chemical engineer is taking raw materials and making something else out of it. So it made sense, and I started researching how to make vodka, and that really sparked the idea back around 2007. I didn’t open up until last year, so it was a full 10 years from concept to product.

JM: That’s a long time to wait to turn your first coin …

JT: It is, but I did it all myself. I didn’t have any investors, so I just saved my money and did it on the weekends for the longest time. In 2010, I bought my fermenters; at the end of 2011 was able to get this property rezoned; and [I] purchased it January of 2012. A few months later, the shell of the building went up and the interior developed over the next year. In 2013, I finished the interior and actually sold my house and moved into this space before all the equipment was ever set up. [I] continued to save my money, finally quitting my job at Sasol in 2014. In 2015 and ‘16, I cashed in my retirement and 401(k), pension, refinanced my truck … really just put it all on the line.

I was staying with family and friends and rented rooms and finally just recently bought the little house next door. So I really had to sacrifice for a few years to make it happen.

JM: So people by now have seen the moonshine reality shows. So from a chemical engineering standpoint, what is different about your process and the way you make your vodka than what most people might think?

JT: The biggest difference is the raw materials. In 2007, when I first started researching it, I had never heard of a sugarcane vodka. But when I looked up the government’s standards of identity, I found that vodka could be made from anything as long as it’s distilled to 95 percent by volume; is treated to remove impurities; and is bottled to at least 40 percent alcohol.

In that process, everything has to be broken down from starches into sugars for the yeast to consume it and produce alcohol. So I thought, why deal with all the solids and the mess, and, literally, letting the raw materials start to rot before it ferments when here in Louisiana we’ve got lots of sugarcane. Why not use that?

It was also around that time that I learned that a lot of distilleries buy alcohol in bulk; [it’s] just called “grain neutral spirits” (GNS) — essentially, bulk Everclear. It’s already distilled, fermented and made from whichever grain you choose, and they just sell it to you in bulk. That’s why there’s not a lot of difference in how vodkas taste, because they are all starting with those exact same base spirits. That’s not to say you can’t make good product from it; plenty of companies do. But I wanted this to be genuine, craft vodka from start to finish — not starting with materials that are 95 percent complete. The distillation is going to set it apart, because if you aren’t doing all of the distillation yourself, you only have so much control over the quantity. And I think we discard a larger quantity of light material and methanol. And the more of that you get rid of that, the higher quality product you have.

Finally, the filtration will set it apart. The system we use is probably the only one of its kind in the United States. I found a company between Russia and Central Europe supplying over 200 distilleries over there — literally, the vodka motherland — and their product was the most technically advanced that I could find. I had to get an interpreter and convince them that I wasn’t going to ruin their reputation in an untapped market over here with an inferior product. That, I feel, has made an incredible difference.

JM: So, how do you take local grown cane and make it into vodka? Are you using the cane itself, or extracting the juice and working with that, or what?

JT: So, I purchase crystalized, non-GMO cane sugar from Louisiana Sugar Refinery (LSR), which is a co-op of 12 or 13 Louisiana families that have their own sugar mills where they take Louisiana cane, squeeze it to get the juice and make raw sugar from it. LSR will take their product and clean it up to remove mud and molasses, essentially. That process allows the sugar to keep longer so we can store it here. It does cost more, but that is just another step towards quality in our process.

JM: But in my mind, a clear spirit made from cane products has always been white rum. How is this a vodka and not a rum?

JT: Well, there are a few big differences between the products. Vodka, by definition, is more neutral; and in rum, you are looking for more of the characteristics of the fermentation material to come through. Legally speaking, according to the federal standards of identity, rum has to be made from cane-based products [from which] vodka can be [made]. Molasses and raw sugar are more traditionally used in rum. But I’m using finished crystalized sugar for my vodka, and that’s already setting it on more of a neutral path, so it really almost is in its own category … But that’s the difference in the fermentation products.

Then in distillation, vodka has to be distilled to at least 95 percent alcohol by volume (190 proof) and rum has to be distilled below that. Then in filtration, vodka must be treated where rum does not [have to be], even though many rum manufacturers will filter it for quality purposes.

Finally, there are the allowable additives. I actually had to contact the Tax and Trade Bureau and speak to their lab to get the specifics on that. I found out that you can add only 2 grams of sugar per liter (1.5 grams per fifth) to vodka once it is finished to back-sweeten it. For domestically produced rum, you can add 2.5 weight percent sugar or caramel, which is something like 17 to 18 grams of sugar per fifth — over 10 times as much.

At first, the bureau told me I couldn’t make vodka from sugar; that I had to use grain. But it wasn’t specifically stated as such in their criteria. Fortunately, someone else had fought that battle legally while I was still researching that process, and that made things much easier when it came time to move forward.

JM: That’s actually quite interesting. I’ve always perceived vodka as just about the most boring spirit out there. It was always flavorless, odorless “get ya’ drunk” juice.

JT: Yeah, and full of that burn …

JM: Right? The only flavor was that isopropyl-esque burn. But drinking yours today, at room temperature no less, that absolutely is not there, and that’s pretty staggering to me, to be honest.

JT: Yeah. Room temperature is just something you don’t do with vodka. People have seen me order it at Restaurant Calla or someplace like that, neat, in a snifter and people are like, “What are you doing? That’s not a wine or anything” until they try it and it really does open their eyes.

JM: So, you said you’re a year and a half out now from your first bottle?

JT: For the very first bottle, I actually had to sneak away on Christmas Day of 2016 because I wanted to have it for Christmas presents, but didn’t have it ready in time. So, I came over for the second day of filtration, and finished the first batch. And even though I was all by myself on Christmas Day, it was honestly the best Christmas present ever. I was even able to get some bottled and back to the family in time for everyone to get their quiet Christmas Day buzz, and it was a pretty emotional day for me.

The following April is when we started selling [the bottles] from the distillery, and it was in November of 2017 that Southwest Beverage picked up distribution.

JM: How wide is your distribution now?

JT: Their footprint is pretty wide, getting up to Alexandria and DeRidder and throughout multiple parishes. Just last week, we signed on with Schilling Distribution in Lafayette. So we now have pretty much all of Southwest Louisiana and Lafayette.

We’re still waiting on some of the bigger outfits like Sam’s and Walmart and the casinos, but we’re in the process for things like Rite Aid and Walgreens. So other than a few of those exceptions, we’re pretty much everywhere in that distribution area.

JM: So, from a business perspective, why did you think Southwest Louisiana needed a craft vodka? Outside of the fact that you wanted to make vodka, what made you think that this was commercially viable and worth investing a decade of research, quitting your refinery gig and putting it all on the line, and being able to be profitable in the process?

JT: Well, most of that decade was research and just trying things with it and experimenting with it at home. It wasn’t until I had spent years working on it in my spare time; getting feedback from friends and family; that I got to try it. And really believing that I had a quality comparable to what’s on the shelf, I decided to go for it. That, and Southwest Louisiana didn’t have its own vodka, so the door was wide open for that. I really had no idea if it would work. I could always sell it all off and go back to engineering. But I had to buy land and build a building, which is a huge investment. I had to have my equipment on order before I could even apply for my permit.

I didn’t see a problem with that process. It would make tax revenue both locally and for the state. But anything could have happened. It was a big risk.

JM: What is your production capacity right now?

JM: The 150-gallon kettle and 8-inch (diameter) column can produce 50 gallons of vodka per 10-hour day. Between that and our fermentation capacity, we can push out 3,000 to 4,000 bottles per month, max. With the current distribution and expected distribution in Lafayette, and maybe Houma, we’re hoping to soon see sales of 1,500 to 2,000 bottles per month. Once we reach that point, I want to pay off some debt and start expanding.

Companies that purchase GNS simply have to write a bigger check to improve capacity. I’ll need bigger and newer everything to start moving into Texas and other coastal markets where I think this brand would resonate.

JM: And it is a brand that can be strong outside this area. I was recently interviewing Eric Avery of Crying Eagle, and he mentioned the brand issues they had with “The Chuck” outside of the immediate area. Have you had any unexpected hang-ups or issues like that?

JT: As far as the branding goes, you’re exactly right. I always wanted it to be very localized in its production and materials, but I didn’t want it to not have an impact elsewhere. That’s why I didn’t plaster a big Louisiana shape on the bottle. We have a small Louisiana on the back of the bottle as a nod to our home and our roots, but I had to put my customer cap on in regard to people from other states. As a vodka customer, that wasn’t too difficult; and I could see that turning someone off who isn’t from here.

As far as problems, the first was one of liquidity. I wasn’t planning to open the distillery for public sales last April. But I, quite literally, ran out of money. I had a couple of batches made, and didn’t know if I was quite ready to roll out from a consistency standpoint. But I had $3,000 in bills due at the end of the week. So I threw it up on Facebook on a Tuesday and had the bills payed by Friday and sold out of the first batches within a couple of months. But that also really helped to light a fire under the product and helped speed it to market.

Another issue was the unique taste. I knew it was different and I wanted it to be. That wasn’t a problem with package liquor sales, which were really strong right off the bat. But bartenders were finding that it just didn’t mix the same as other vodkas in certain cocktails. Craft places like Calla picked right up on it because they are looking for different and unique products to work with. But other places reached out and said they really needed our help in making it work for them.

JM: That could be a bit of a blessing and curse. Not only did you have to be innovative with your product and the process, but you had to get innovative with the application of the product as well.

JT: And I’ve never been any kind of mixologist, so I had to ask what their best-selling vodka cocktails were, and started trying to find what worked and why. Vodka tonics and vodka and soda were two standouts. They usually call for a lime, but I found that using lemon, with its difference in sweetness and acidity, actually worked much better when using Yellowfin in those cocktails. Same went with a Cosmo. That’s not across the board, though. A mojito is still a mojito, so the traditional preparation still worked best. A Moscow Mule was the same way.

Other issues surfaced with the distillation set-up itself. There were some inherent flaws in the system when I got it. Originally, the column was three separate columns, and the manufacturer couldn’t understand what the issue was and why that needed to change. I literally had to prove to them scientifically and mathematically why this system, as designed, wasn’t producing the volume it should. The easiest of the options was stacking the three columns into the one super-tall column you see here. [Doing that] literally quadrupled the production and fit all that work into one 10-hour work day as opposed to me having to pull a mattress in here and sleep with a timer on my phone to wake me up every 30 minutes to check on it overnight.

After all that, they actually started changing what they were doing at the manufacturing facility based on these innovations. That, and it’s safer now. I did hazard analysis when I was working at the plants, and some things in this product made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. So I changed every single gasket that came with this system as soon as it got here and made some other adjustments. That helped the manufacturer out in their process a lot as well.

JM: So tell me about the system itself. I know you have pot and column stills, so this is obviously a column still …

JT: Well, it’s kind of both, actually. This is a batch system, in that it doesn’t run continuously like a normal column would, and it uses both a kettle and a column. The kettle has an oil jacket around it that’s used to heat the product instead of having a heating element in the product itself. The gentler, indirect heat reduces scorching or putting undesirable flavors into the product. Normally, you would use a mash tun to cook your materials to get your base. But since I’m starting with the sugar itself, it goes directly into the kettle to melt it all down. That is then moved into the fermenters, and fermented into a 15 percent alcohol-by-volume sugar wine, essentially. After that, we take it from the fermenter and put the wine back into the kettle and boil it, which sends the product through the column, where the separation begins.

Walter Hammond, Jamison Trouth and Aaron Beale at Yellowfin’s production facility in Sulphur • Photo By Lindsey Janies

There are 22 stages of separation and 20 is about the bare minimum needed to turn a 15 percent wine into a 95 percent neutral spirit. Other distilleries who purchase NGS and only have few stages of separation will distill; empty and refill the kettle; and keep repeating that over and over. They’ll advertise that it’s 5 or 10 times distilled. But if they’re using a system like this, they’re exposing the alcohol to a lot of air. While it’s not a fine wine, it does the same thing. That exposure of alcohol to oxygen still creates acids and esters and all other kinds of nerdy chemistry stuff that taste bad. That’s why I kind of laugh when I hear of a product that is “X” times distilled, because it sounds good from a marketing standpoint, but I’d like to educate people on reality instead of just throwing buzz words at them.

And that goes beyond vodka. I want to do an oak-aged vodka. Never been done before to my knowledge, but I think it would be cool — certainly with the complexity and difference in this product. I went to a bourbon distillery to learn more about it, and when I got there, they told me they didn’t use barrels. We’re talking whiskey here; how do you not use barrels? I found out that they buy bulk bourbon and NGS, spike the bourbon with neutral spirits, filter it and put it in the bottle. No barrels, no wooden staves, nothing to age … just nothing. It happens everywhere, and no one knows it. Sure, it’s more cost-effective. That’s the guys who can increase capacity by writing a bigger check. But if quality is the goal, you have to be more committed and involved than that.

JM: So what does the future hold for you and Yellowfin Vodka?

JT: You know, I think the name of the game is just to push to capacity, pay down the debt, put some money in the bank and expand. I’d love to have this stuff from Texas to Florida, eventually. If it was in demand enough, I could see this in bigger cities. There’s tuna fishing all along all the coasts of the United States, so I really don’t know what to expect, but we’ll see.

As it is now, it’s pretty bare-bones. But I want to integrate more controls and meters into this system, so it will get way more complicated in time. We’re still applying labels by hand at this point.

We’ve started a bottle recycling program. People love these bottles and the glass cork and didn’t want to throw them away. So, we had to go to the federal government; question the bureau’s wording when they told me that I wasn’t allowed to refill; and get them talking with state agencies to eventually find out that, legally, while we can’t refill customers bottles, we can recycle them and give the consumer a discount on bottle purchases here at the distillery. So, we can take a bottle from a customer, clean it and sterilize it using our vodka, fill it, reseal it and sell it back to them. So it’s even better than recycling, since we don’t have to melt all the glass down and remake the bottles. That makes it more affordable for the consumer, keeps our production costs down and is better for the environment at the end of the day. Most manufacturers wouldn’t even fool with that, but what we do here is about more than just making vodka. It’s just another thing that makes us and our product different, and I’m very proud of that.

—————————————

These differences and many more make an impact not only on the product in the glass but also to the change that a business with this kind of philosophy can make in the community from which it hails. Even a small, Sulphur-based vodka distillery can make sure that its process uses locally sourced ingredients; find ways to lessen environmental impact; and pursue a level of quality in their craft that defies even the spirits industry’s standards of profitability and maximizing margins.

Sure, he could make it cheaper. Sure, he could make the same type of compromises other manufacturers make. He could follow the path other leading “craft” manufacturers have taken and let someone else make the bulk of their product. That’s not what he’s here to do. He has, instead, chosen not only to expand the Bayou State’s presence in the burgeoning craft booze market, but also to do so in a way and with a product the likes of which no one, anywhere, has really ever seen.

Making a dollar may not be easy, but making one while being innovative in the product, the process, the application and even by innovating elements of the manufacturers of distilling equipment are no easy tasks. But they all genuinely reinforce Trouth’s vision, talent and commitment to making something new, different and implicitly Southwest Louisiana. In the process, he’s left this vodka hater sitting here bewildered at the fact what he once saw as a lifeless, empty spirit now has complexity, character, depth and purpose — as well as a story that he genuinely hopes will be told for a long time to come.

It looks like I may have been wrong about vodka after all. It just took finally finding one worth believing in.

Comments are closed.