President Trump recently unveiled the framework of his tax reform plan. The details were sketchy and the blanks — of which there are many — still have to be filled in by congressional tax committees. Here is what Trump wants Congress to do:

Estimates are that these reforms will reduce the federal government’s revenue by 1.5 trillion to 2 trillion dollars over the next decade. But the details aren’t yet known, so these are just rough guesses. They ignore how these tax changes might spur economic growth, which is a critical issue because our nation is presently $20 trillion in debt.

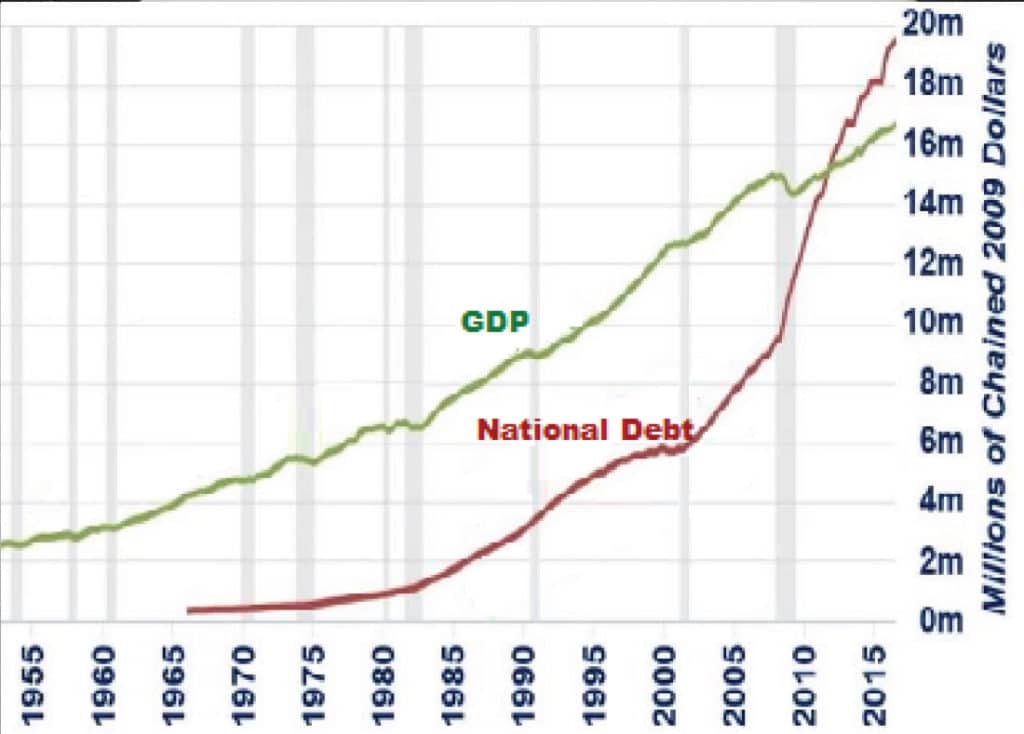

The danger of a nation’s debt is generally gauged by its debt-to-GDP ratio, which measures how long it would take a country to pay off its debt if it devoted all its economic activity to doing so. A ratio greater than 77 percent is generally a sign of trouble. The U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio rose above 77 percent during World War II, but returned to the safe level until 2009, when the Great Recession lowered tax receipts and Congress increased spending for the Economic Stimulus Act, TARP, and two wars. The ratio has remained above 100 percent since then.

There are only two ways for the federal government to reduce its debt: it can either reduce spending or increase revenue. It is essentially impossible for the federal government to reduce its spending to the point that it won’t need to borrow money because of programs like Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. Another thing that makes spending cuts difficult is that the Federal government pays more than $250 billion a year in interest on the debt.

The Trump administration recently released its 2018 budget plan, which includes spending and revenue projections to 2027. Their budgets would eliminate many programs and significantly cut others. They say this will eliminate the budget deficit within a decade. That doesn’t mean the national debt will be eliminated in 10 years; it means the debt will stop growing in 10 years. The budget deficit is the amount added to the debt each year.

Under the Trump budgets, as austere as they may be, we will add another $4 trillion to the national debt over the next 10 years — and that’s before considering the impact Trump’s tax reform will have on government revenue.

The argument the Trump administration is making is that the only way to get back to the debt safe-zone (that is, under 77 percent of our GDP) is by growing our economy, and they are willing to gamble that by cutting taxes and increasing spending on productive assets such as infrastructure, which will increase the national debt in the short run. These actions will grow the economy in the long run to bring our debt back to the safe-zone (that is, less than 77 percent of our GDP).

While on the campaign trail, Trump said his reforms would produce annual economic growth of 6-7 percent. That’s probably not realistic — at least not for a protracted period. Steve Mnuchin, Trump’s Treasury Secretary, said he expects growth to be closer to 3-4 percent annually over the next 10 years. That may not sound spectacular, but it is considerably better than the 1.48 percent growth during President Obama’s eight years in office; and it’s enough to get our debt back to the safe-zone if — and it’s a big “if” — Trump can keep a lid on government spending.

My concern with Trump’s tax plan is two-fold. First, I’m not sure his tax cuts will boost the economy as much as he hopes; historically, tax cuts have increased our budget deficits. Second, I’m not sure he can cut spending as much as he hopes; there are too many unknowns out there — hurricanes, wars, global recessions, etc. — that are potential budget-busters.

Tax reform is about how the government raises its revenue, not how much revenue it raises. We need tax simplification and tax relief for the middle class. But most analysis indicates the bulk of the proposed tax reduction will go to the wealthy.

Do we really want to raise the debt limit so we can borrow more money from overseas to finance tax cuts for the wealthy? If these tax cuts would stimulate the economy enough to maintain tax revenue at its current level — that is, if they were “revenue neutral” — I’d be fine with them. But I’m not 100 percent convinced the reason investment is going overseas is because taxes on the wealthy are too high in the United States.

A bigger deterrent to production in the United States is the cost of compliance with our bureaucratic regulations. That is where Republicans need to focus to stimulate the economy.

Comments are closed.