A Rough Guide To Distinguishing Between Louisiana’s Cajuns And Creoles

By Brad Goins

One way to distinguish between Cajuns and Creoles is to look at where they came from.

Cajuns came from the Acadians, who traveled from French-speaking settlements in Canada and settled in Southwest Louisiana. Creoles, on the other hand, are the descendants of people who came from Europe, Africa and the Caribbean to Louisiana during its colonial period (that is, before it became one of the states of the USA).

One reason it’s not always easy to distinguish Cajuns from Creoles is that both peoples came from French-speaking areas. But there’s quite a bit of difference between Cajun French and Louisiana Creole.

During the 18th century, 7,000 European immigrants settled in Louisiana. Many of these immigrants came by way of Caribbean islands.

At the end of the 18th century, the revolution in French-speaking Haiti brought a flood of 4,000 additional refugees to New Orleans. Many of these were descended from Africans.

Early in the 18th century, New Orleanians used the term “Creole” to describe descendants of immigrants who had been born on the soil of Louisiana. The term had practical value, as it differentiated a French-speaking person who’d been born in Louisiana from one who’d traveled to the colony from Europe.

When New Orleanians called children of immigrants Creoles, they were using a term they were familiar with. The term “Creole” was developed in the 16th century to describe descendants of French, Spanish or Portuguese settlers in the West Indies and Latin America. It’s probably derived from the Portuguese term “crioulo,” which meant a slave born in the house of its master.

There were two prominent groups of Creoles in early New Orleans. One was made up of the children of upper-class French or Spanish settlers who were often plantation owners or government officials. Another group was made up of descendants of free blacks or those who were of mixed European and African descent. These were the Creoles of Color.

Descendants of the French and Spanish were happy to call themselves “Creole” because the term differentiated them from the Anglo-Saxon whites settling in Louisiana.

The Creoles of Color also became prominent people in New Orleans, with almost half of them prosperous enough to own slaves. Members of this group used the term “Creoles of Color” to distinguish themselves from other blacks in the country. After the Civil War, Creoles of Color who appeared to be of African descent were grouped together with other blacks in Louisiana.

After the Civil War, the most controversial issue related to Creoles was the persistent but erroneous notion that all Creoles have someone of African descent among their ancestors. Today, different sorts of issues can arise when Creoles with dark skin feel that they are pressured to call themselves “black” or “African-American.” With Creole, it is the same as with Cajun — those who use the term to describe themselves usually make a conscious choice to do so.

Creole Culture

Louisiana folklore scholar Nicholas R. Spitzer states that in Southwest Louisiana, the term Creole tends to represent a mixture of ethnicities and influences; in New Orleans, the term continues to emphasize the central importance of European heritage.

Spitzer also says the term “creolization” is used to describe “the mingling of cultures in South Louisiana.”

In the pre-Civil War past, traditional Parisian French was spoken by wealthy Creoles, while Louisiana Creole tended to be spoken by working Creole whites and blacks in rural areas.

Creoles have traditionally valued economic independence. They have traditionally seen education as the best way to obtain economic stability in the face of changing economic conditions.

Although most Creoles practice Catholicism, some practice Voodoo, which is itself a mixture of Catholicism and African religions.

Creole traditions include the practice of making leisurely greetings to friends or relatives one sees sitting on porches. People are likewise encouraged to make meals a leisurely affair, rather than an occasion for wolfing down food.

The ability to speak French is endorsed. However, some say the practice of speaking French is becoming rare among present-day Creole youth.

In the past, the location of weekly Creole dances was marked by the placement of a tall pole. These dances were attended by all, and particularly by country folks, who placed great importance on these opportunities for socializing. In contrast, early Mardi Gras balls were reserved for Creoles of wealth and influence. Participation was definitely by invitation only.

In his book Gombo Zhebes: Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs, writer Lafcadio Hearn provided many Creole sayings. Some of these were quite clever and insightful; examples include:

“He who takes a partner takes a master.”

“The coward lives a long time.”

“The monkey smothers its child by hugging it too much.”

Some of the sayings are obviously expressions of a distinctly Creole culture:

“Conversation is the food of the ears.”

“Good coffee and Protestants are seldom, if ever, seen together.”

Creole Food

Creole foods developed in the Louisiana bayous where communities of Creoles settled. The foods reflect the same ethnic mix as the people: French, Spanish, African, Native American and Caribbean.

Sauces are much more prominent in Creole cooking than in Cajun.

Tony Chachere’s spices and foods are phenomenally popular in Southwest Louisiana. Many consumers may never have noticed that Chachere’s slogan is “Famous Creole Cuisine” — words that appear on a bright yellow banner on the front of Tony Chachere products.

While Chachere spent his childhood as a Creole in New Orleans, he became a world famous cook and cooking show host when he lived near our neck of the woods in Opelousas.

Chachere’s description of Creole gumbo emphasizes the way the various ethnicities connected with Creoles contributed to the dish. Onions, peppers and tomatoes came from the Spanish influence; filé (or ground sassafras leaves) came from Native Americans; the roux came from the French and the spices from the Caribbean.

Chachere says Creole jambalaya is “red jambalya.” It includes ham, sausage and tomato. Red jambalaya has a tomato base; however, its color is largely a product of its use of shrimp stock. Cajuns favor a “brown jambalaya” that’s made with a fried flour roux and sometimes uses tasso (smoked pork).

Chachere shares the Creole’s emphasis on the cultural significance of the meal; he says, “Creole cooking is the distinguishing feature of Creole homes, where a meal is a celebration, not just a means of addressing hunger pangs.”

Creole foods can vary markedly in different parts of Louisiana. For example, the use of tomato decreases the closer one gets to Southwest Louisiana.

One major similarity between the Cajun and the Creole is that both are acutely aware that much of their cuisine is derived from French food. This can be seen in Cajun food in its strong emphasis on white bread, and in particular, on French bread made from finely ground wheat flour. Southwest Louisiana is one of the places in the world where diners can be heard judging sandwiches primarily in terms of the quality of their bread.

Early French settlers in Louisiana declined to grow corn (rather than wheat) even when the government of Louisiana offered them free seed and financial stipends to grow corn.

In Southwest Louisiana, Cajun and Creole share a love for such French-influenced dishes as meat pies and crawfish pie, which obviously rely heavily on the French tradition of buttery, flaky and tender crust.

Creole Music

Zydeco music is most closely identified with modern Louisiana Creoles. It developed early in the last century. Zydeco features the accordion and washboard, which is often called a “rub board” or “frottoir.” (Although the frottoir is largely associated with zydeco, the word is derived from the French Cajun verb “frotter,” which means simply “to rub.”)

Again, the music is a blend, mixing indigenous Louisiana music, Creole music and rhythm and blues. Its upbeat sound means it places less focus than Cajun music on ballads set to a slow dancing tempo.

Clifton Chenier may have been the first musician to make zydeco known to the country at large. Buckwheat Zydeco certainly enjoyed the greatest national success and recognition as a zydeco player. Creole musicians who remain prominent in the Lake Area at present include Geno Delafose and Sean and Chris Ardoin.

Famous Creoles

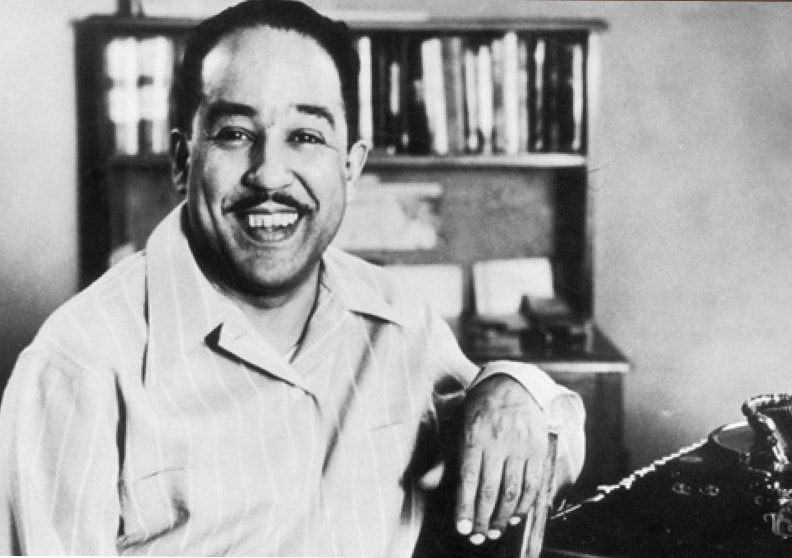

Creoles have left an especially strong mark on American literature. Kate Chopin, who’s best known for her work The Awakening, wrote much widely read fiction about Creoles in rural Louisiana. Poet and Harlem Renaissance leader Langston Hughes and black history writer W.E. DuBois were both Creoles.

Historical Creole figures include leading Confederate Gen. Beauregard; Emiliano Zapata, leader of the Mexican Revolution; civil rights leader Rosa Parks; and Marie Laveau, who is considered by many to be the leading Voodoo figure of Louisiana.

Creoles dominated early jazz music, with such leaders as “Jelly Roll” Morton, Illinois Jacquet, Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet all being of Creole origin. R&B master Fats Domino was also a Creole.

Creole actor Joan Bennett was in Hollywood at the very beginning of the film era, becoming the wife of one of the earliest major directors, William Fox, namesake of the Fox entertainment group. She appeared in her first film at the age of 4. She established herself as one of the premier femmes fatales of film noir, and wound up her career by playing Elizabeth Stoddard in the cult TV series Dark Shadows.

Another Creole Hollywood star was Dorothy Lamour, who was routinely cast as an exotic due to her olive skin and long black hair.

Prominent contemporary Creoles include the singers Beyoncé and Carly Simon, rapper Ice-T and the television emcee Bryant Gumbel.

Creole figures who are especially well known in Southwest Louisiana include the pirate Jean Lafitte and Ret. Lt. Gen. Russel Honore, who oversaw the effort to rebuild Cameron after Hurricane Rita.

Cajun Versus Creole

Overall, there may be as many similarities as differences between the two groups. In both groups, there’s an emphasis on French language and food derived from French food. The accordion is central to the music, and the “Holy Trinity” of onion, celery and green pepper is central to both cuisines. Upbeat Cajun music can sound very similar to zydeco, and both are considered to be forms of American roots music.

For both groups, Catholicism is the dominant faith.

There is a shared reliance on making use of what one’s given.

But some broad differences are likely to remain. Those who embrace their Creole heritage will have a keen awareness of either European or African (or Caribbean) roots, while Cajuns will always tend to think of themselves of exiles of Canada who were victimized by the British.

Creoles also seem to see a greater role for education in the economics of the community.

To date, Creoles have probably had a somewhat greater influence on American culture at large. The fact that many descended from ancestors who enjoyed a culture of refinement, education and wealth in New Orleans was probably a good springboard into the larger culture.

A Rich Mix Of Music, Food And Ritual

Now, we’ll take a look at the ways in which Creole culture established itself in Southwest Louisiana. In particular, we’ll look at the music (such as that of Boozoo Chavis and Geno Delafose) and the phenomenon of the Creole cowboy.

But before we get down to these cultural phenomena, let’s briefly consider the history of Southwest Louisiana Creoles and how they established themselves in the area.

Before the Civil War era, the term Creole was used in Louisiana to describe “free people of color” (genres libres de couleur) who had both European and African ancestors. Free people of color settled in large numbers in Southwest Louisiana early in the 19th century.

Like many others in the country, they were moving west from plantations in search of their own farms and ranches. Some free people of color who acquired large tracts of Southwest Louisiana land wound up owning slaves themselves.

Creoles settled in the bayous and piney woods areas of Southwest Louisiana, in places with such names as Prairie Laurent, Frilot Cove and L’Anse Prien Noir.

One such place, Pied des Chiens, is the location of the well-known Creole community of Dog Hill, which is south of Lake Charles. The late Boozoo Chavis, who was both a famous zydeco musician and a Creole rancher and cowboy, came from Pied des Chiens.

Creoles moved into the Texas Gulf Coast shortly after they came to Southwest Louisiana. They again settled in very rural locales, such as Double Bayou. Having, for the most part, started from the large urban area of New Orleans, they would eventually spread out to large urban locations, such as Houston, and, eventually, Los Angeles.

Mixture Of Cultures

“Creole” developed from the Portuguese word “crioulo” which means a native of a given area. Creolization is a term for the mingling of numerous cultures in South Louisiana. A Creole is a person who may have black, Spanish, French and Indian ancestors.

According to Dr. Nicholas R. Spitzer, a professor of folklore cultural conservation at the University of New Orleans, Creolization is most common in areas where residents eat gumbo and listen to and perform Cajun music.

This is one sure indication that Creoles mixed thoroughly with Cajuns in the areas they moved into. As a result, Creoles adapted much of the food, language, music, Catholicism, language and festivals of the Cajuns.

The mixture of cultures is also indicated when the word Creole is used to describe language. The Creole language is considered to be an African-French language that’s used in South Louisiana and the French West Indies.

From the time of its development, the Port of New Orleans was the recipient of heavy usage by those in the Caribbean. Before the Civil War, the port was the largest in the U.S. It was hardly remarkable that a strong Caribbean culture developed early on in New Orleans.

Among Creoles, there was a gradual westward movement from New Orleans. Eventually, Creoles of Color settled in especially large numbers in the land around Cane River, below Natchitoches. To the west of Natchitoches lives a group of Spanish-speaking people who have a lineage that includes the Choctaw Indians. This latter group has interacted to a great degree with the Creoles.

More On Music

Creole music hasn’t made the impact on recorded music and popular culture that Cajun music and zydeco have. But Creole music is still performed throughout Louisiana, and there’s plenty of recorded Creole music for those who don’t live in Creole communities.

The roots of today’s Creole music lie in the 17th century, when slaves from Africa and the West Indies brought their own music here. Many of these slave musicians were musically diverse from the beginning. In addition to their own African music, they knew folk music and opera tunes from Europe, French and Spanish baroque classical music and hymns that were sung in church.

Instruments they relied on included the fiddle, the African version of the banjo (the banza) and, of course, the African drums. Early Creole musicians quickly incorporated the banjo music that was being played throughout the American colonies and the Caribbean into their own styles of performance.

Spitzer goes so far as to say that zydeco is a form of Creole music. (He thinks the term “zydeco” may have come from a Creole French saying about “les haricots” [the green beans]; the Creole French saying indicates that times are really hard when “zydeco sont pas salé” [the beans aren’t salted].)

Creole fiddler and guitarist D’Jalma Garnier says Creole musicians have a tendency to “bend” notes, meaning that they’ll go up or down the range of a note on all the instruments in the ensemble. He says this process results in the “finger glissandos” used by Creole fiddlers and the “hollers” of vocalists. Fiddlers also practice the “slurring” of numerous notes in a single bowstroke. “Though Bébé Carriére plays tunes that are melodically simple, his bow technique can take a lot of unlearning for classically trained musicians,” says Garnier.

Garnier believes that Canray Fontenot stood alone as the star of Louisiana Creole fiddle playing. (In Juke Blues, writer Paul Harris called Fontenot “the greatest black Louisiana French fiddler of our times.”) Garnier recommends the Arhoolie album Louisiana Hot Sauce, Creole style, as an introduction to Fontenot’s music.

For a bluesy Creole fiddle, Garnier suggests the work of Morris Chenier on Arhoolie release Bon Ton Roulet & More. And to hear Garnier’s fiddling, listen to Poullard, Poullard & Garnier on Louisiana Radio Records.

Creole Cowboys

Every Labor Day weekend, more than 3,000 Creoles from this state and Texas gather for a trail ride through rural areas of Southwest Louisiana. Some wear elaborate cowboy outfits; some dress in jeans and athletic shoes.

These cowboys see themselves as part of “le monde Creole” (the Creole Community). For this reason, they promote their own communities, wearing shirts that salute such groups as the Labeau Posse Trailriders or the Original Cowboyz.

Folklorist Nick Spitzer says the tradition of the Creole cowboy is one of hard working and hard playing. But he also says that today’s trail rides are “leisurely.” (They may be too leisurely for some. Spitzer quotes a Texas Creole cowboy as saying, “Everything just goes too easy. I like rough, rough stuff.”)

Trail rides last from a few hours to more than a week. Riders stop at each Creole community along the route. They may also stop to listen to the music of such outfits as Jeffery Broussard and the Creole Cowboys. If they cook during the ride, they dine on such foods as gumbo, jambalaya and cowboy stew, which is made of tripe.

Creole cowboys were established along the Gulf Coast in the 18th century. They drove cattle through Louisiana and part of Texas on the way north.

When these cowboys settled in Southwest Louisiana, horses were used for ranching and transportation, says Spitzer. Horses could also be used for escape from slavery, which explains why Creole cowboys still see the horse as a symbol of freedom and independence.

Creole cowboys eventually developed their own horse: the Creole pony, which was a mix of Indian horses, wild horses and horses that had been imported by the Spanish and French.

Creole cowboys who lived and worked in Southwest Louisiana developed the skills needed to herd cattle across bayous, use the Indians’ Catahoula hounds for herding, and hunt feral hogs. Spitzer quotes this story from Boozoo Chavis:

“Let me tell you about my grandpa and my uncle. They’d go out and catch them horses. It was on Johnson’s Bayou in Cameron parish by the water. And they’d sleep at night, right on that water … They’d build a fire for the wild hogs. And they’d watch them horses there …

“The next morning, they’d rope the horse and they’d get two, three men, and they’d catch that horse. And they … put a saddle on him, and they’d ride him. He’d buck, buck and they’d ride him till he quit bucking … You’d ride him half a day or something until he’d get burnt out. They’d rope another one, a wild one, and they’d get on him … And the boss man … the white man, would sit in his car, in his truck … The car or truck only went so far.” (Quoted in “Zydeco Trail Ride: Creole Cowboys at Work and Play.” One of Chavis’ albums was titled Zydeco Trail Ride.)

Musician Geno Delafose, who has a wide following in the Lake Charles area, described his cowboy experience to Spitzer:

“You don’t see too many black cowboys. Especially up in the northeast … So first they have a black guy wearing western clothes, playing an accordion. And then, when he opens his mouth, he’s singing French. So that really throws them for a loop.”

Creole horsemanship now often takes the form of sport or cultural celebration, such as quarter horse racing and Mardi Gras trail rides (during which some cowboys play fiddle and accordion at each house visited).

If you want to know more about Creole ways, Creole food or the impact of Creoles in this area, there’s a wealth of information at the Louisiana’s Living Traditions web site. Visit louisianafolklife.org.

Comments are closed.