Lost Lake Charles by Adley Cormier.

Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2017,

136 pp., $21.99

A Review By Brad Goins

Photos provided by McNeese Archives

Adley Cormier isn’t the first person to publish a book-length history that covers Lake Charles from its beginning to the present. Be he’s the first to do so with a book that’s primarily text.

Cormier takes a distinctive approach in his history. He places an unusual emphasis on form and place. He’s careful to delineate the particulars of major commercial and domestic buildings and architectural trends.

While this has been done before, what is new in this book is Cormier’s meticulous description of the city’s sections, whether they’re devoted to business or habitation. Cormier is especially novel in plotting the history of the city’s suburban developments — from the first to the latest. He shows how old or original sections were sometimes assimilated by new suburbs.

He also explains the ways in which the most recent suburban developments show an awareness of smart use of land that was lacking even in suburbs built in the postwar 20th century. He goes into detail about the aspects of “land-conscious” development at Walnut Grove and Graywood.

His focus on the uses and arrangements of land is well summed up in this paragraph:

“Having no bedrock (no rock at all to speak of) on which to build, and with a surface area of malleable marsh, prairie, woodland and open water, Lake Charles has seen major alterations and changes to its physical appearance in its 150-year history. Man has cut canals, drained marshes, cut over timberland, raised fill and altered watercourses. Add the occasional flood, hurricane and fire, and the man-made environment of the Lake Area has been in a state of near-constant flux from the day of its first settlement.”

Cormier’s broad focus on structures and the organization of their placement on land affects the depiction of history in the book. Events that have a profound effect on architecture or the organization of business or living areas or the plotting of streets are emphasized. For instance, the history of the lumber trade, the 1910 Fire and the dredging of the deep water channel for the Lake Charles port are related in abundant detail.

Of course, the stated purpose of Cormier’s book is to tell the story of important aspects of Lake Charles that have been lost. As one would expect, much attention is devoted to such losses as those of the timber and rice industries; the life of the city’s red light district — Railroad Avenue, also known as “Battle Road”; and the concentration of the city’s commerce and social life in the downtown.

‘Remote, Hard To Get To And Underpopulated’

One strength of Cormier’s book is its meticulous attention to the time before the city was incorporated under the name “Lake Charles” in 1867 — a period that often receives pretty scant attention.

Cormier takes his story way back to the Ishak Indians, who once lived here. The Ishak were also known as Attakapas, which, Cormier says, is a Chitimacha term that means “man-eaters.” Early French and Spanish soldiers were told (whether rightly or wrongly) that the Ishak were cannibals.

The Ishak were also called the “Sunrise People.” They were divided into two main groups: those east of the Sabine River and those west.

Cormier says there are no known archeological remnants of the Ishak — perhaps the first major loss covered in this book of loss. However, the Ishak’s influence lives on in the term “Calcasieu” — an Ishak word for “crying eagle.”

Western settlers in the area established “a self-reliant culture of cattle grazing, subsistence farming, hunting and fishing,” writes Cormier. Early Lake Charles wasn’t part of the plantation culture that was the source of such turmoil during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Part of the reason was that Southwest Louisiana was “not directly connected by water to the rest of Louisiana.” For this reason, Southwest Louisiana was “literally off the radar” of French and Spanish settlers during the colonial period. When the Spanish took charge of Louisiana in the 1760s, they viewed Southwest Louisiana as “remote, hard to get to and underpopulated.”

This isolation continued right through the Louisiana Purchase, which did not include “much of Southwest Louisiana.”

The result of all this was the well-known “neutral strip” or “no man’s land” — a place where criminal activity flourished in many regions.

The beginning of the end of the neutral strip took place in Lake Charles, when the U.S. military built the Canton Atkinson on the east shore of Lake Charles around 1819.

The fort “consolidated the western boundary of the state and of the United States.” While the structure of the fort is one of the things that have been lost, its existence did coincide with the beginnings of the Bilbo Cemetery — the earliest remaining evidence of a U.S. presence in Southwest Louisiana.

‘A North American Cowboy Culture’

By the 1770s, the French were beginning to grant long, narrow land parcels to settlers who could make up their minds to live in what is now Lake Charles. The first such parcels were sold to Barthelme LeBleu. Charles Sallier (the city’s namesake) was the first to settle within the area enclosed in the present day city limits. Michel de Pithon came soon after.

“Water — either river or lake — borders the entire northern and western edges of the city,” writes Cormier. Much of the city’s early commerce had to do with water-related trade and use of resources. In addition to fishing, hunting and trapping were resources in this formative stage of the area. As cattle drives were added to the mix in the 1780s, the area saw the “birth of a North American cowboy culture.”

It took some time — half a century, in fact — until this early nuts-and-bolts rural community had acquired sufficient population to enable it to be “subdivided into streets and developments.”

Early town leader Jacob Ryan, who had “extensive land patents ranged on both sides of the Calcasieu River,” worked with feverish energy to plot the young city’s streets.

Lumber, Shipbuilding And Shingles

A short time later, Germans — many of them “Michigan Men” — migrated in large numbers to oversee Lake Charles’ new lumber business and the creation of a “booming shipbuilding industry,” headed by Capt. Daniel Goos. This German migration explains the street names of Fitzenreiter, Prater and Moeling in the Goosport area.

In the 1850s, Goos’ three steam-powered upright saws produced 11,000 board feet of lumber daily. When his son-in-law, George Locke, got his own steam saw, the two cranked out 4 million board feet of cypress in their first year.

The Goos lumber enterprise is another part of history lost; its commercial buildings are “now long-erased.”

In 1857, the small city incorporated as “Charleston.” It acquired a mayor and aldermen and a “public burying ground for protestants.” Although a portion of this “Magnolia” or “Corporation Cemetery” can still be seen at the northeast corner of Moss and Church Streets, most of it was removed for the creation of I-10.

In 1867, the settlement was incorporated again, this time as “Lake Charles.”

The Michigan Men streamed in, bringing with them the knowledge and creativity that spawned Lake Charles’ distinctive residential architecture. Although the arrival of the Michigan Men is now seen as a good thing, Cormier reminds the reader that some at the time would have seen them as the notorious “carpetbaggers” or “scalawags” of the Reconstruction — ambitious northern entrepreneurs set on building businesses out of Southern ruin and disorganization.

One Michigan man, William Ramsay, acquired 150,000 acres of virgin woods in the Lake Area. He aggressively marketed the area’s woods, sending samples of cypress and heart pine to contractors through the North.

Ramsay also created mills that manufactured not boards, but “windows, doors, shingles and shutters.” And he paid his workers in currency — not in company script.

All 17 of the once bustling lumber mills of the Lake Area are lost, as is most of the cypress and heart pine that made them known throughout the country.

Railroads And Rice

Lake Charles was cutting down its timber fast. It was a good thing for the fledgling city that the railroads were coming.

Since Lake Charles was largely isolated by its waterways, a trip from New Orleans was an arduous six-day affair that went partly by water, partly over land. The opening of the Lake Charles Louisiana-Western Railroad and Depot in 1878 cut that travel time to 8 hours.

In addition to the Southern Pacific and Kansas City Southern Line and Depot, the late 19th century saw the creation of a railway line by leading local businessman Jabez Bunting Watkins. The Watkins/Iron Mountain/Missouri Pacific Depot was located right across the street from where the transportation center stands today.

Spurs from the railroads brought abundant resources to “serve the developing cattle, rice, sulfur, lumber and petrochemical industries.”

Watkins had good reason for building up a local railroad empire. In 1880, he had bought no fewer than 1.5 million acres of land in Southwest Louisiana. To the entire U.S., Watkins promoted the area as an agricultural paradise where prices were low and abundant fruit could be grown with little labor. He advertised his wonderland by means of national newspaper ads, direct mail and his railroads, and poured funds into the promotion by means of his national bank.

Watkins’ efforts would usher in the area’s next big boom. With the land virtually deforested, Watkins enlisted the aid of agricultural expert Samuel K. Knapp to build a rice-growing empire. By 1912, the business had grown to the point that the price for all 100-pound bags of rice in the U.S. “was set on the docks of the Lake Charles Mills.” In another 14 years, Lake Charles would be the site of the world’s largest rice mill.

This and other business developments enabled Lake Charles to increase its population by 400 percent during its railroad era (1880-1920). The swelling numbers included second-generation German, British and Irish; French and German Jews; and immigrants from Syria, Lebanon, Italy, Denmark, Hungary and Scandinavia.

‘The Original Streetcar Division’

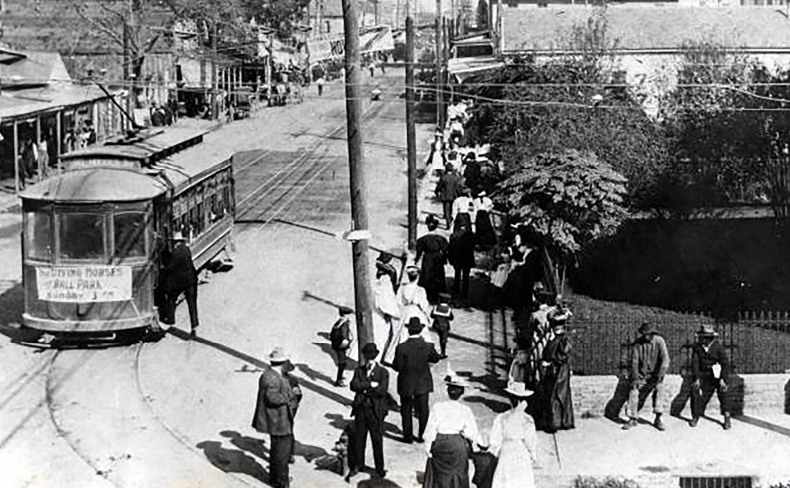

In 1891, the earliest mass transit took the form of “mule-driven cars” that carried passengers back and forth between wild and rowdy Railroad Avenue and Ryan Street, the early city’s center for shopping.

It took 15 years, but all lines eventually ran on electricity.

In the 1910s, mass transit was seen as a good means of expanding the city. Streetcar lines ran seven days a week, 24 hours a day — a system that puts today’s minimal mass transit to shame. Cormier writes, “the entire city benefitted from improved streetcar access to education, jobs, church and entertainment.”

Cormier says Margaret Place was “the original streetcar division.” Its streetcars took riders to the Barbe Pleasure Pier and Casino and other popular destinations for entertainment and diversion.

Readers may be surprised to learn that this early transit system split into two routes at South Street (today’s DeBakey) and Miller Ave. (today’s 7th Street). As late as the 1920s, the city’s effective southern boundaries were far north of where they are today.

Cormier maintains that “the direction of growth [of Lake Charles] has been generally southward and toward the east.” He feels that the major leap in this growth took place more than 100 years ago, when the Lake Charles Country Club was established at Prien Lake.

One of the Lake Charles divisions, subdivisions or “villages” that Cormier examines is the Charpentier District — a village of almost 50 blocks — that was the destination for many of the “Michigan Men” who oversaw the creation of many of the local homes of the leaders in the lumber industry. Many of the homes in the district used the cypress and pine harvested during the timber boom.

A Disaster Waiting To Happen

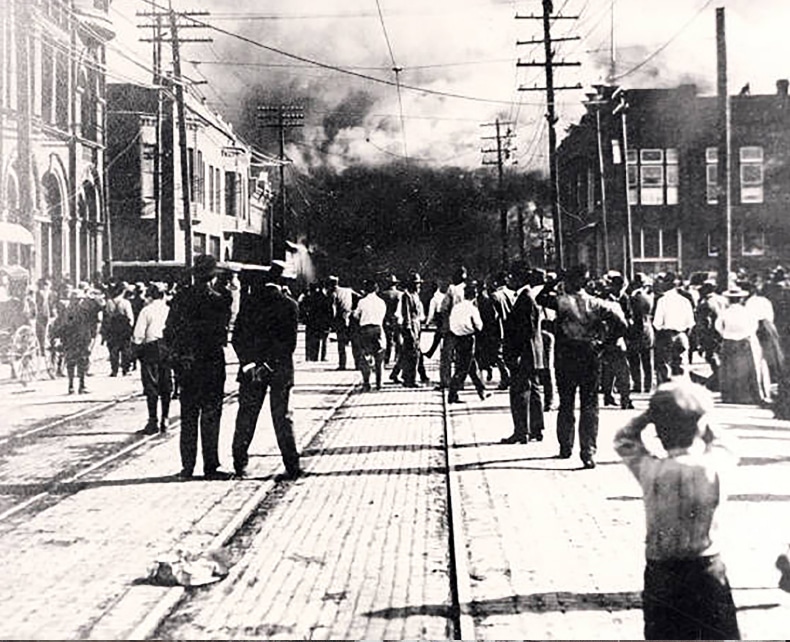

In this era, Lake Charles was built with a wood-centered style of architecture that would cost the city terrible losses in the Great Fire of 1910. Cormier carefully sets the stage for the event by noting that not only were most commercial buildings in the city made of wood, but their roofs were covered with cedar shingles that enabled sparks to spread easily from building to building. Only a few buildings, such as The Majestic Hotel, as well as Gordon’s Drugs (now the Pujo Street Cafe), were made of brick.

Lake Charles’ population was 15,000 on the Saturday afternoon of April 23, 1910, when a small trash fire sat burning behind a downtown opera house. The buildings in the city were tightly packed together, with Lake Charles’ de facto boundaries set at Railroad Avenue to the north, Boulevard (now Enterprise) to the east, the Pithon Coulee to the south and the river to the west. A total of 350 buildings were crammed onto the town’s main thoroughfare — Ryan Street.

Gale force winds blew sparks from the trash fire onto the opera house. Its construction of heart pine was “rich in pitch and tar.” Its well-maintained floors were “regularly oiled and waxed.” It was a tinder box. And like many other downtown buildings, it was linked to adjoining buildings with connecting walls.

Wind quickly spread sparks from the opera house flames to the Catholic church (then made of wood). As the flames spread to more and more buildings, firefighters started using dynamite to create firebreaks.

The Majestic Hotel had its own power and water supply. It continually hosed down the buildings around the hotel, thus saving them from fire. It would go on to house people who were made refugees by the fire, which would eventually make a third of Lake Charles homeless. Rice mills provided free boiled rice for the homeless.

The fire’s reach extended from Ryan Street to Kirkman. It would eventually burn up seven full blocks and destroyed 109 buildings.

A New Kind Of Architecture

After the fire, it was time for the city to re-assess. Lake Charles called in the New Orleans architectural firm of Favrot and Livaudais to lead the way in the creation of modern, fire-resistant buildings. There would be a conscious move away from buildings that were “quickly run up from materials at hand” and “utilitarian in form.” The new buildings would generate respect and admiration, as well as commerce.

Favrot and Livaudais’ first effort was the ornate Mediterranean-style City Hall of 1911, whose tile roof, and building materials of brick, marble, terra cotta and bronze, would not be susceptible to flames.

The two created the new Immaculate Conception Church with its Romanesque design and deep red brick. The church resumed its function of being “the only Catholic Church to serve a region of over five thousand square miles.”

The firm went on to design several downtown landmarks built to survive the ravages of fire.

‘A Powerhouse Industrial Combination’

The decline of the rice industry and the influence of two world wars brought new business booms into the area. WWI brought the massive military training airbase called Gerstner Air Field — the training grounds for such future military leader as Gens. Claire Chennault and Jimmy Doolittle. Cormier notes that not all of this base was lost, as one building was moved to Kirby Street, where it currently houses the Church of Christ, Scientist.

WWII brought the Lake Charles Army Airfield (which serviced the Third Air Force) and the Korean War brought the Lake Charles Air Force Base, which was named for Gen. Chennault in 1958. It was used by the Strategic Air Command until it was returned to public and commercial use in 1963.

WWII also accelerated Lake Charles’ standing as a center of petrochemical refining. Usually revivals, Continental Oil (Conoco) and City Services united for the war effort to make petrochem products needed to run U.S. tanks and war planes.

Cormier succinctly describes the conditions that enabled subsequent development: “The unique juncture of resources, water access (via barge, port and intracoastal canal), pipelines and highways made for a powerhouse industrial combination on the western shore.”

Cormier takes great care in explaining how water transport was dramatically enhanced by citizens’ efforts in the 1920s to alter the Calcasieu River so that it could accommodate almost all boat traffic to and from the Gulf. Working without any government assistance, citizens “reshap(ed) the river, straightening the course of the lower Calcasieu River, cutting through a series of horse shoe bends and dredging the shallow lagoon-like lakes to shorten and deepen the route to the Gulf.”

When the last dredging effort was completed in 1941, the distance of water travel from the Gulf to Lake Charles had been reduced from 75 miles to 33.

Not every development in transportation worked in the city’s favor. When the interstate was constructed in the 1950s, it “block[ed] street flow a mere three blocks from [the city’s] busy core. The interstate at this point appeared to be designed to move traffic through Lake Charles and not into Lake Charles, a merchant’s fear …”

Suburbanization And A Civic Center

It should be noted that Cormier’s section on “Suburbanization” is indicative of another emphasis that’s not found in other historical writings. His sketch of 75 years of suburbanization places particular emphasis on Oak Park and Graywood.

Cormier also provides a thorough examination of the effect of the Lake Charles Civic Center on the Lake Charles downtown. The Center had been intended to draw support from surrounding hotels. But it was completed, Cormier says, “too late” to do this.

Probably a more important factor in the Civic Center’s failure to launch was “the perceived disconnection to the downtown it borders.” Cormier cites city planner Andres Duany, who says the massive parking lot, Lakeshore Drive and a block of law-oriented office buildings create “a psychological and physical barrier” between the Civic Center and the downtown.

The Paramount, The Pitt And The Palace

Cormier’s main concerns in the book ensure that it isn’t devoted to a large degree to the city’s cultural and social life. However, a chapter devoted to popular culture does provide illuminating information.

For instance, Cormier explains that early in the 20th century, Lake Charles was known for its “Sunday shows.” The Sunday show developed because entertainment acts that had closed their New Orleans runs on a Saturday night could head through Lake Charles the next day and get in one more Louisiana show before leaving the state. Such famous figures as Houdini, Isadora Duncan and the Barrymores stopped off in Lake Charles to perform at the Arcade Theater, the Pleasure Palace or the Lyric Theater.

Cormier’s treatment of Rosa Hart, while by no means exhaustive, is enjoyable and informative reading.

Toward the end of the book, Cormier devotes a section to the 11 lost buildings that have been recognized by the Calcasieu Historical Preservation Society’s plan to commemorate “Lost Landmarks” with historical signs that tell the story of the landmarks’ lost history.

Among these lost buildings is Ball’s Auditorium (formerly at Enterprise and St. John Street), at which the likes of James Brown, Ray Charles and Otis Redding once performed.

Cormier also notes that more than 20 movie theaters have been lost in the city’s long regression to the multiplex of today. Among these lost theaters are the Paramount, the Pitt, the Delta, the Ritz and the Palace.

An Enjoyable Experience

This review only touches on a small part of the information included in Lost Lake Charles. I’ve tried to choose this sampling of information in such a way that it reflects Cormier’s areas of focus.

Cormier’s prose is smooth and readable and his historical narrative moves at a steady pace. At 136 pages, the book can be read in one long afternoon.

For history lovers, or those especially interested in Lake Charles, a reading of this volume will be an enjoyable experience. And its emphasis on certain areas that haven’t really been covered before means that even researchers are likely to learn some things they didn’t know before.

Cormier’s Lost Lake Charles is published by Arcadia Publishing’s prestigious The History Press, which has already published a couple of fine books of Lake Charles history and photography.

Comments are closed.