Stephen Hebert Is Driving His Bluesmobile In The Great American Race

Story By Brad Goins

Photos By Jason Carroll – monsoursphotography.net

Special Thanks To Port Aggregates

Stephen Hebert retired young. Today he lives with his family in his rural Westlake home. Family and friends often accompany Hebert as he strolls around the grounds with his little dog.

But it’s not a quiet life. Not by a long shot. The country calm is often broken by the explosive roar of a car engine that runs well in excess of 500 horsepower; by the screech of tires that peel out on the driveway as a vehicle accelerates to lightning speed in a few seconds.

Hebert is a lifelong auto mechanic. Today, his big retirement project is taking vintage muscle cars and working on them until they become formidable drag racers. And when he’s made the car right for the track, he drives it in national races.

The fruit of Hebert’s labor is a group of retooled muscle cars. Like many muscle car enthusiasts, Hebert is a big fan of the Hemi engine.

He says the 1966 Dodge Coronet 426 Hemi was the first vehicle that offered the car-buying public the option of getting a car with a Hemi engine. Because the Hemi engine had such power, cars that had one came with only a 90-day warranty. This limited warranty and the challenges of maintenance ensured that the buying public lost its taste for the souped-up car pretty quickly, and it was soon taken out of production.

Today, Hebert owns two of these rare cars. One is the 1966 Dodge Hemi Coronet Hebert calls the Green Machine. An automatic, it was one of only 18 made.

Hebert also owns a 1966 Dodge Hemi Coronet 4-speed trans car — one of just 31 made. These cars could be sold as a matching set one day. Even one of the cars can easily sell for well over $100,000.

The Hemi engine was developed in the early 1960s by Tom Hoover, a physicist and automotive engineer who’d been hired by Chrysler. It was he who assembled the world’s first 426 Hemi V-8 engine.

Hoover’s Hemi engine was so good for stock car racing that in 1964, Richard Petty drove his Plymouth Hemis to nine victories. Chevrolet threatened to sue its racing rival, arguing that the technology being used on the track was inappropriate because it wasn’t available to the general public.

For one year — 1965 — no one could drive a Hemi engine in stock car racing. So in 1966, as was noted above, Dodge offered the Hemi to the public, and Hemi stock car racing was back on the menu. As usual, the new set of rules and regulations didn’t make a whole lot of difference. In 1967, Petty came back with his Plymouth Hemis and won an astonishing 27 races in a single year.

After 1966, the public could get a Hemi, but it came at a price. One of Hebert’s old muscle cars still has the original price sheet attached to its window. The base price was $2,397. With the Hemi engine, the car’s cost shot up by $1,113.

As the movie the Blues Brothers makes clear, old Dodges had a distinct connection with U.S. law enforcement. Hebert notes that the FBI requested two of the 1966 Dodge Hemis, asking that the vehicles be outfitted with trailer hitches so that they could tow crime scene trailers.

The Bluesmobile

Hebert’s refurbished and rebuilt many cars so that they’re race track-ready. Not long ago, he finished building his version of the car used in the movie The Blues Brothers. When he was done, he told his brother-in-law Dennis.

“I built the FBI car,” he said.

“Well, we ought to be the Blues Brothers,” was the response.

With that, the brother-in-law began his transformation into Dennis “Elwood” O’Connell. (One of the film’s two protagonists, Elwood Blues, was portrayed by Dan Akroyd.) When the two men take this vehicle to the upcoming Great American Race, Hebert will sit in the passenger seat as Stephen “Joliet Jake” Hebert (the complement of Jake Blues, as played by John Belushi in the film). By the time race day arrives, both men will have done their best to look the part of the two movie characters.

O’Connell — once an F-4 fighter pilot in Vietnam — makes a good, assertive driver. Hebert, who will be the navigator for the car in this year’s Great American Race, has a big cup of underliners he uses to keep the numbers from running together in his head. (In a minute, I’ll explain just what it is that makes it such a challenge to navigate one of these races.)

Like any good police car/drag racer hybrid, Hebert’s Bluesmobile features a 400-watt siren. That’s 400 watts of amplification for whatever sounds Hebert puts into the vehicle’s police radio. He has a machine that generates a variety of audio clips from the Blues Brothers movie. So racers may soon hear John Belushi’s angry voice screaming full tilt from a giant speaker.

Won’t racing officials be irked by these extremely — and I mean extremely — loud sounds? “At times, we’ll be able to use it,” says a smiling Hebert.

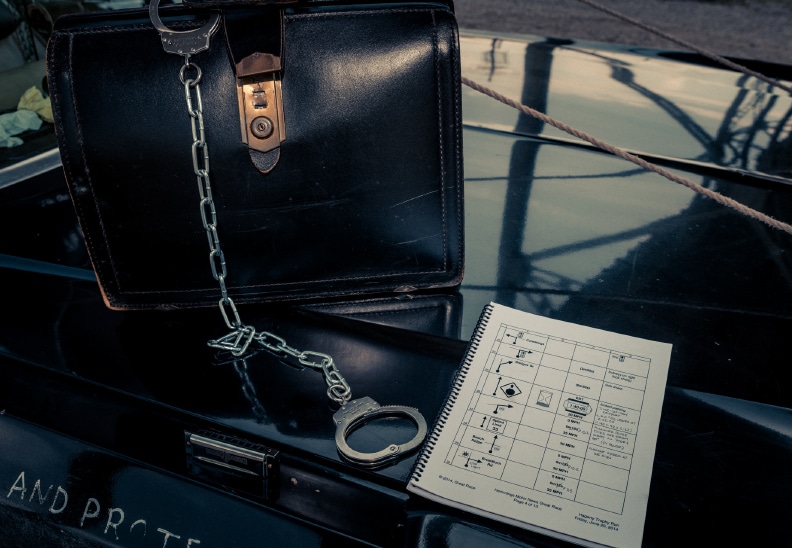

Just as on the exterior of the vehicle in the movie, a police star on each front door of the original car is clumsily covered with black paint. The car bears the handwritten slogan “TO SERVE AND PROTECT.” A large decal on the back reads, “Our Lady of Blessed Acceleration, Don’t Fail Me Now.” The license is a faithful BDR 529, with BDR standing for “Black Diamond Rider.”

The car contains a black briefcase with handcuffs on the handle just like in the movie. The top of the dash is cluttered with old packs of Chesterfields and watched over by a Holy Mary figurine. Hebert’s Bluesmobile also has an 8-track player (which was playing an Olivia Newton John tape on the day I interviewed Hebert).

The vehicle is a 1974 Dodge Monaco, but it’s not a Hemi. This edition had a 440 wedge motor. It was a “police package” — designed specifically for law enforcement — and was plenty powerful.

In the film The Blues Brothers, when Jake is astonished by the speed of the car, Elwood tells him it’s the fastest car around because “it’s got a cop motor, a 440 cubic inch plant. It’s got cop tires, cop suspension, cop shocks.”

In 1974, Dodge released its Monaco Police Pursuit vehicle. It had a 440 High Performance Magnum engine. Obviously, the car was designed for law enforcement agents who were eager to get an edge on criminals who were reckless drivers, speed freaks or unusually talented at getaway driving.

Hebert shows me the car’s original speedometer, which went up to 140. He also notes the word “CERTIFIED” that appears over the speedometer. The word “certified” was a tacit contract with law enforcement that they could get the vehicle to travel as fast as 140 mph.

Producers and directors used 12 of these cars in the filming of The Blues Brothers. Over 100 cars of other makes were wrecked during the filming.

On top of the Bluesmobile in the movie, and the one in Hebert’s garage, is an addition found on no standard issue police car — a giant CLM air raid siren. Hebert readily admits the siren is just a prop. “A real one would crush the car,” he says.

When I rather sheepishly ask whether the huge contraption creates much wind resistance, Hebert immediately admits it does. It’s important to keep in mind that this car, for Hebert, is more about fun than winning. “It’s the cheapest and slowest car we’ve got. But style and attitude is our theme” at this year’s Great American Race. “It’s probably going to be the most fun we’ll have this year … I can’t wait.”

The Great American Race

The Great American Race is a timed event. Each racer must take off at a time calculated down to the second. A total of 120 racers compete, with a new racer taking off every minute.

Each racer is given an exact starting time. Suppose Hebert is the 71st racer on the list. That means he must add 71 minutes to the starting time he is given.

He must also start from the exact starting location he is given. Hebert showed me the instructions for a single day’s race — pages of instructions that tell him which locations he must go to and in what order. In the course he showed me, he was obliged to start at a traffic sign shaped a certain way.

And just finding the right sign isn’t the end of it. As navigator, Hebert is constantly crunching numbers. For instance, he shows me a chart that lets him know that if he wants to get up to 50 mph at the moment he starts, he’ll need to accelerate the Bluesmobile for 8.2 seconds. It’s not just careful navigation, says Hebert; “It’s a math quiz.”

It’s not necessarily a race for super-fast cars. Some like to drive very old antique cars. Why? Such cars get a great handicap.

Hebert mentions the 1916 American LaFrance, which gets a 50-percent handicap in the race. His Bluesmobile will receive no handicap due to its youth.

The Great American Race is limited to cars manufactured in 1972 and earlier. Hebert had to get special permission to drive his 1974 issue Bluesmobile.

The race changes its route each year. The first year Hebert participated, the route ran along Route 66. Last year, it corresponded to the Lincoln Highway, and this year it will follow the Dixie Highway. “For the most part, we’re running the old highways,” says Hebert.

This year, the race’s grand master will be “Big Daddy” Don Garlets, whom Hebert calls the “godfather of drag racing.” (Garlets is considered the inventor of both the slingshot drag racer and the top fuel car.)

At each day’s stop, there will be two hours of public viewing of the cars. These viewings have long been celebratory events that draw large, enthusiastic crowds.

This year’s Great American Race will begin in late June in Jacksonville, Fla., and end in early July in Michigan. It’s a 2,300-mile route.

Racing Career

Hebert won the NHRA SPORTSNational drag race in 2009 with the 1968 Barracuda Hemi that he calls Secretariat. He’s continued to compete in the race, which in recent years has often been held in Bowling Green, Ky.

Of course, it’s not easy to win a race. “There’s plenty of ways to lose,” says Hebert. One way is with fouls. No driver in any stock car race can accelerate before the starting light turns green. One year Hebert was disqualified for starting 3/100 of a second before the light changed color.

Driving Secretariat, Hebert has won at two national drag racing events and been runner-up at two others. He says, “I am the only reason the car does not win every event.”

All sorts of things have been done to keep down the weight and wind resistance of this good-looking bright blue racer. The car has fiberglass fenders; Hebert explains, “if they did it at the factory, we can do it … Anything that was done at the factory, a drag racer can do.”

Secretariat’s seat belts come up through the roll cage; the glass is much thinner than that of standard-issue windows. The car must come in at the NHRA’s weight limit of 3,200 pounds.

Hebert explains that it was only in 1968 that Hemi engines were offered in “the small A body cars.” Only 70 Dodge Darts and 70 Plymouth Barracudas were made with the Hemis in this body in ‘68. The cars are now very rare.

Hebert says he makes Secretariat a persistent winner by popping it up to 10,000 rpm.

Green Machine

One of Hebert’s racers is called the Green Machine. It’s striking — a beautifully unrestored and well maintained vintage muscle car. And it has fierce power. Hebert calls it “the perfect race car.”

He last ran the Green Machine — a shiny, olive green 1966 Dodge Coronet Hemi 426 — at the Great American Race. It was the second time he’d driven the car in the race. The splendid racing machine was performing just as it should until a wheel bearing broke.

At the time this Coronet was available to the public, all Dodge coupes with Hemi engines were convertibles. It’s clear that the top of the Green Machine has been welded at the spot where the convertible top once rose up. On the underside of the car, one can see the huge torque box that was once used to stabilize the structurally weak convertible top.

At one point, Hebert shows me a recent bill of sale for a car of the same make. The price is $660,000.

The Fastest Muscle Car Of All

Hebert’s 1968 Chrysler-Hurst Dart Hemi was a joint venture between Chrysler and Hurst. When Hurst was finished working on the basic vehicle produced by Chrysler, the car had the two rows of four cylinders that were standard for the Hemi engine. The horsepower announced to the public was 425. Many thought the actual HP was probably about 535. Street Muscle Magazine declares that the car is the “fastest muscle car of all time.” And Hebert says, “these things are engineering marvels.”

Its price (high for the time) was $5,000. Hebert says the vehicle is now “strictly a museum piece,” and shows me the rot that is clearly visible on the original tires. The car still bears the black and grey primer with which it was first coated.

What a person such as Hebert does with this vehicle is “take the skin off, build a chassis car, then put the skin back on.” Look inside the passenger window and you’ll see the huge roll bars and straps you typically associate with the interior of stock car racing coupes.

Hebert’s Background

Hebert recalls that in the early 1970s, his mother told him, “You’re not going to amount to anything. You just work on cars.”

Hebert must have taken the message to heart; he learned to work on something else.

The first thing he did was build his mother a new handicap-accessible home. Then, when he could, he went back to working on cars.

Eventually, he learned enough to develop geospatial software and hardware that was able to map places on land as well as under water. He built up his company to the point that it had 174 employees and developed classified proprietary mapping techniques still in use today.

By 2008, the U.S. Dept. of Defense had taken notice. Hebert sold his operation to Northrop Grumman and bought a big chunk of the company’s stock. At the age of 52, he found himself retired and financially independent. He could go back to doing what he’d wanted to do all along: working on cars.

The Ugly Stick

Let’s wind up by taking a look at one more of Hebert’s racers.

As accustomed as driver and brother-in-law O’Connell is at wrestling powerful race cars down the track, he declines to take the wheel of one of Hebert’s cars: The Ugly Stick. O’Connell thinks the car just has too much power to handle.

The car is a 1966 Dodge Coronet 426 Hemi. Hebert has seen to it that the bad boy is badder than ever, as it now houses a 650 horsepower engine. Hebert says he “put overdrive in it” to make it the power factory it is. Hebert can get the car up to 161.11 mph in 1,300 feet. “It is a bad boy street car,” he says.

On the back is a decal that reads “You’re beat with the ugly stick.” And as far as exterior aesthetics go, the car does look ugly. There appears to have been little if any maintenance of the car’s original paint job. Rust now plays a major part in its look. So do dents.

But Hebert values this car for its speed and power; not its looks. He took me out for a brief ride in The Ugly Stick. I expected it to do a lot and it did even more.

As Hebert rushed down deserted rural roads, I felt my back being pressed back hard against my seat. I’d experienced a bit of this in a retooled GTO in high school.

What was entirely new to me was the vibrations under my feet. They were powerful, steady, forceful, non-stop vibrations that produced a variety of loud rumbling sounds. At times, I felt as if my feet were jumping 3 or 4 inches off the floor. This was a first for me.

I guessed that if this sort of vibration went on for long, it must have some sort of effect on human feet. I don’t want to think what it must do to a human body to sit in one car seat and race for eight consecutive hours.

I said a little about this to Hebert, and he conceded that such events as the Great American Race take a toll on the body.

Still, it’s hard to gauge the value of the exhilaration one feels when a driver lets loose in a monster race car. Such exhilaration might be worth a fair amount of inconvenience and pain.

Maybe that sort of exhilaration is important to Hebert. At any rate, it’s clear that he derives a great deal of joy from doing what he does. As far as I can see, his cars keep him smiling.

Comments are closed.