Cajun Dancehall Heyday: A History of Traditional Cajun Music in the Lake Area of Southwest Louisiana and the Golden Triangle of Texas by Ron Yule. (2017, DeRidder, Fiddle Country Publishing, 365 pp.)

Review By Brad Goins

The great deed has finally been done and the result is a coffee table book that looks quite spiffy and can double as a handy reference tool.

As was mentioned, the volume is encyclopedic in length, scope and organization. Much of the book is devoted to alphabetical listings of descriptions of musicians and musical acts. There are many dozens of photographs. The volume’s 11-by-17 inch pages total 365 in number.

Early Cajun Music

The Manuel Family -B. D. Williams, Ralph Richardson, Abe Manuel, Lenny Benoit, Pop Benoit, and Joe Manuel, 1942. Photo courtesy of Ralph Richardson.

Yule’s introductory section on early Cajun music in Calcasieu Parish focuses on musicians who came into their own in the 1920s. One of these was Arsene St. Mary, a Little Indian Bayou resident who played not so much “the real stomp down zydeco” as music his friends called “off the wall,” which was a term for “older folk songs which were seldom recorded.”

He actually wound up playing the “rub board” (frottoir) in California, where he moved in 1964.

With the end of World War II, says Yule, returning soldiers gave the accordion a new place of importance in Cajun music. When Harry Choates’ “Jole Blon” went to No. 4 on Billboard’s charts in 1946, the country learned what Cajun music was. Such Lake Charles instrument builders as Sidney Brown, Valentine Lopez and Charlie Ortega got busy building diatonic accordions, also known as “melodeons.” These increased the versatility of accordion players, who, by pushing a single melody button, were able to play one note as the instrument was pushed and another note as it was pulled.

“Chun” Vincent Family Creole, late 1940s. Linda “Pishue” Vincent (Dahlen), “Chun” Vincent, Dorothy “Dottie” Vincent (Manuel). Photo courtesy of Dorothy Manuel.

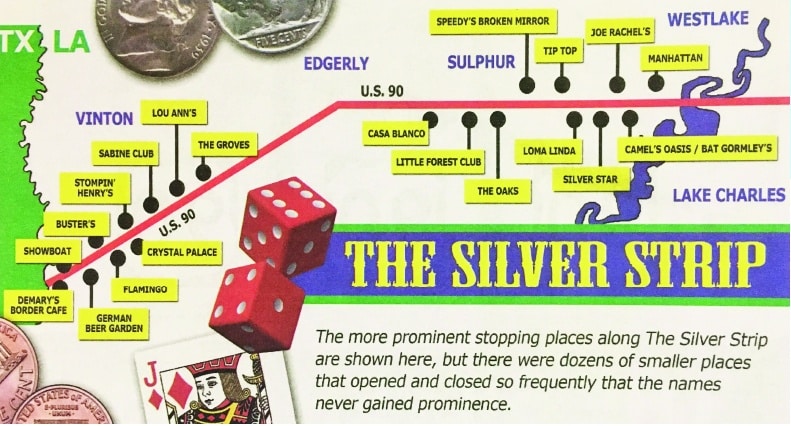

The reader is given a map and a brief run-down of the “Silver Strip” of rowdy night spots that once crowded the stretch of Highway 90 west of the Calcasieu River. The stretch included 26 clubs from Vinton to Westlake that Texans who were willing to take the ferry could go to to indulge in beer and gambling. These were hot spots for Cajun music and dancing until the style of music began to lose its dominance in the area in the 1960s.

Radio And TV

Part of Yule’s introduction covers the effects of recording and radio and television broadcasts on the development of Cajun music.

Radio shows with live Cajun music tended to be broadcast around supper time in Southwest Louisiana. Among these was Eddie Schuler’s 5 pm show on KPLC radio. A longer show was Louisiana Barn Dance, which presented 1 1/2 hours of live music performed at Speedy’s Broken Mirror on Highway 90 at night. The show, which was also called Hillbilly Jamboree, began on KWSL (now KAOK), then moved to KPLC.

Louisiana Hillbillies at KTAG, Lake Charles, 1954. Bradley Stutes, Dottie Manuel, Amos Comeaux, Abe Manuel, Wiley Barkdull. Photo courtesy of Dorothy Manuel

As for television stations, both KTAG (a UHF station) and KPLC were showing Cajun performances on the TV screen in Lake Charles by 1954. Photographs in the book show the Louisiana Hillbillies (with Dottie and Abe Manuel) playing on KTAG in 1954, and the same band playing 11 years later on Saturday Night Down South, a live music show KPLC ran during most of the 1960s.

The Musicmakers

After a brief introduction to music in the Golden Triangle of Texas, a long section titled “Lake Area Musicmakers” provides descriptions of many dozens of Cajun music acts — most of them from much earlier times. The entries are arranged alphabetically according to the names of the acts.

These entries are divvied up among sections titled “The Pioneers (Pre-1945),” “The Legends Are Born (1946-1955”) and “The Tradition Continues (Past 1955).”

Louisiana Hillbillies at Saturday Night Down South – KPLC, 1965. John Lemaire, Abe Manuel, Dottie Manuel, Hermon Lasyone, Glen Croker. Photo courtesy of Dorothy Manuel

An entry on the Hackberry Ramblers spans seven pages, and covers such events as their 1965 trip to the Berkley Folk Festival.

Terry Clement, who started performing “French music” in Crowley in 1949, is quoted as saying, “rock and roll and swamp pop almost killed the Cajun music clubs. Nobody wanted French bands. To survive, we eventually started playing rockabilly and swamp pop.”

In his ultimately successful quest to get back to Cajun music, Clement recorded for both Khoury’s Records and Eddie Schuler’s Goldband label in Lake Charles. When he sent a recording of his tribute song “Jacqueline” to the widow of President Kennedy, he got a thank you note from the White House.

‘Most Men Carried A Very Big Sharp Knife’

The reader is given a map and a brief run-down of the “Silver Strip” of rowdy night spots that once crowded the stretch of Highway 90 west of the Calcasieu River.

The stretch included 26 clubs from Vinton to Westlake that Texans who were willing to take the ferry could go to to indulge in beer and gambling.

These were hot spots for Cajun music and dancing until the style of music began to lose its dominance in the area in the 1960s

One of the alphabetized entries is Lyle Ferbache and Andrew Brown’s fairly lengthy essay on the Pine Grove Boys. The piece describes just how hard life could be for a devoted French musician in SWLA.

Bernella Fruge, wife of band member Atlas Fruge, said, “[Being] married to a musician was a tough life. They had it in their blood and they needed to play. They missed most family activities because they had a club date. Of course, they were always playing on the weekends.

“The ones who had husbands that worked and played music had it worse. Their husbands weren’t home day or night.”

The Pine Grove Boys played at the Avalon Club in Basile every Saturday and Sunday. Fruge played the accordion; Nathan Abshire, who was idolized by many young Cajun musicians, played accordion. The club was often crowded, with several hundred in attendance. And things could get a little rough.

“It was an era when most men carried a very big sharp knife with them,” said Bernella Fruge.

She was working as a stand-in drummer when heavy-drinking fiddler Will Kegley put his hand on her leg. She hit it with a drumstick. Kegley touched her again; Atlas told him to stop.

Kegley wandered over to the bar, then returned to the stage and stabbed Atlas five times in the back. When he turned to face Kegley, Atlas was stabbed two more times in the chest.

Atlas survived the attack, but the Pine Grove Boys were done. Kegley went to jail; Atlas travelled to Texas to play with other musicians.

While The Pine Grove Boys would eventually reassemble with a new line-up, Ferbrache and Brown say their effort to make a go with Swallow Records in 1965 was doomed. The British Invasion had fundamentally altered the world of American music. Swallow Records focused on Cajun musicians who could incorporate British pop styles: Belton Richard, Vince Bruce and Doris Matte.

Ferbrache and Brown write, “The big dance hall days had ended and most other clubs were in the process of shutting down … the rough days of the rowdy honky-tonks were no longer.” They quote Terry Clement as expressing similar sentiments: “We went from playing Cajun music to rock and roll, swamp pop to country. If your band wasn’t versatile, you didn’t work much. Cajun bands were having a hard time of it.”

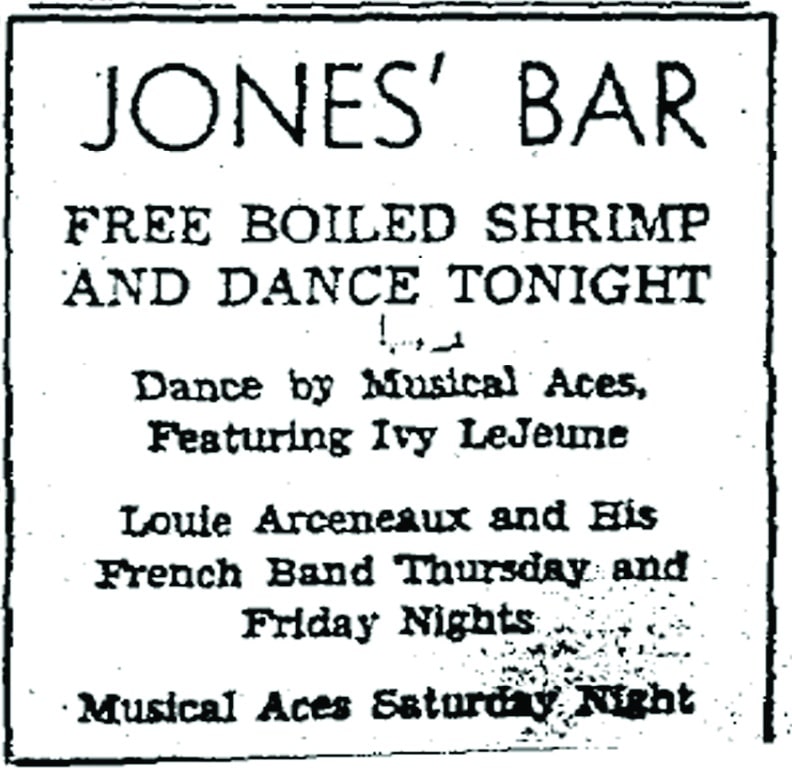

Jones’ Bar

The “Lagniappe” section of the book includes Yule’s “Dances at the Vanicors with Amade” and uncredited essays on The Hurricane of ‘57 and its influence on Cajun Music and on Jones’ Bar.

Jones’ Bar (punctuated in a variety of ways in ads of the time) thrived in the 1940s north of Lake Charles off Highway 171 on English Bayou.

Typical of the area’s Cajun music spots at the time, Jones’ Bar was a dancing spot that attracted its share of patrons who were spoiling for a fight. It was first mentioned in the Lake Charles American Press in 1943 when one of its patrons rested in critical condition in a local hospital after he was stabbed in the venue.

As Carroll Broussard, of Harry Choates’ Jolie Blon Boys, recalled it: “It was a rat place. One night, a guy gets cut; about two nights later they get into a gang fight; and then the last time, they had an armed guy running the place. He comes running after his wife through the bar with a shotgun. But what put the icing on the cake was, when it came time to pay us, they said we owed them money on the bar bill … That’s when I quit [the band].”

Jones’ Bar may have tried to counter its violent image by frequently advertising giveaways of boiled shrimp.

The potential for violence notwithstanding, the Hackberry Ramblers, Iry Lejeune, Harry Choates and the Pine Grove Boys all played at Jones’ Bar at some time.

In seven years, it was gone — sold and renamed Duke’s Bar.

John Lomax And The Broussards

Also appended is Ron Yule and Wade Falcon’s essay “The Broussards at the National Folk Festival.”

In 1934, John Lomax travelled south in search of folk songs he could record for the collection of the Library of Congress. He visited Angola Penitentiary, where he befriended folk singer Lead Belly.

Lead Belly was due for release. He offered to drive Lomax through the deep south, introducing him to indigenous folk music along the way. At least one of the trips brought Lomax through Southwest Louisiana.

Some SWLA musicians felt that Lomax’s recordings would be the break-out that would finally give Cajun music national popularity. Among these were two bands made up of musicians with the last name of Broussard. The Broussard Family came from Lake Arthur and Lawrence Walker and the Acadian Band from Rayne.

Set on riding the Lomax wave, the two Broussard bands won the Lafayette competition that enabled them to be the first Cajun bands ever to perform in the National Folk Festival, which was being held in Dallas in 1936. Another first at that year’s festival was the inclusion of “Negro music.”

An American Press story about the event quoted humorous lines from the song “Allons a Lafayette”: “Don’t ever get married. Flour costs too much.”

The Texas crowd was estimated to number 36,000.

The Broussard Family Band was invited to play at the National Folk Festival in the subsequent year, when the host city was Chicago.

In a sad note, Yule writes, “It seems very few people recalled the monumental events in Dallas and Chicago, and the history of the story practically faded away.” For its real break-out, Cajun music would have to wait until the 1950s, when such performers as the Balfa Family, the Hackberry Ramblers and Canray Fontenot played regularly at the National, Newport and Berkley Folk Festivals.

‘I’ve Exhausted Every Lead’

Cajun Dancehall Heyday’s massive discography is 75 pages long. Long as it is, it’s bound to be incomplete. Yule says repeatedly in the book that due to haphazard book- and note-keeping at the time, the details of many recordings have been lost. Musicians recall that a certain recording was made and released, but no one still has any documentation or any copies of the disc. “I’ve exhausted every lead there is,” Yule told me.

A directory of the region’s musicians runs 23 pages.

Appendices also include a list of dance halls and clubs where Cajun music was played and brief lists of local radio and TV stations and accordion makers. The bibliography runs eight pages and the index six.

Don’t let the dates in this book fool you into thinking Cajun Dancehall Heyday is all about old music. Yule follows some of the more recent acts (and even a few of the older ones) right up to 2016.

This book may never be surpassed as a source of information about Cajun music — and especially recorded Cajun music — in Southwest Louisiana.

You can get a special introductory offer for this large, attractive book by sending $40 plus $5 for shipping (check or money order) to:

Ron Yule

P.O. Box 819

Deridder LA 70634.

If you order more than one book, postage on each additional book is free.

For more info on the book, contact Fiddle Country Publishing at 337-463-5884 or ronyule@gmail.com.

Comments are closed.