A Local Group Uses The Legend Of Jean Lafitte To Promote SWLA’s Biggest Festival

Story By Brad Goins

Main Photo by Jason Carroll

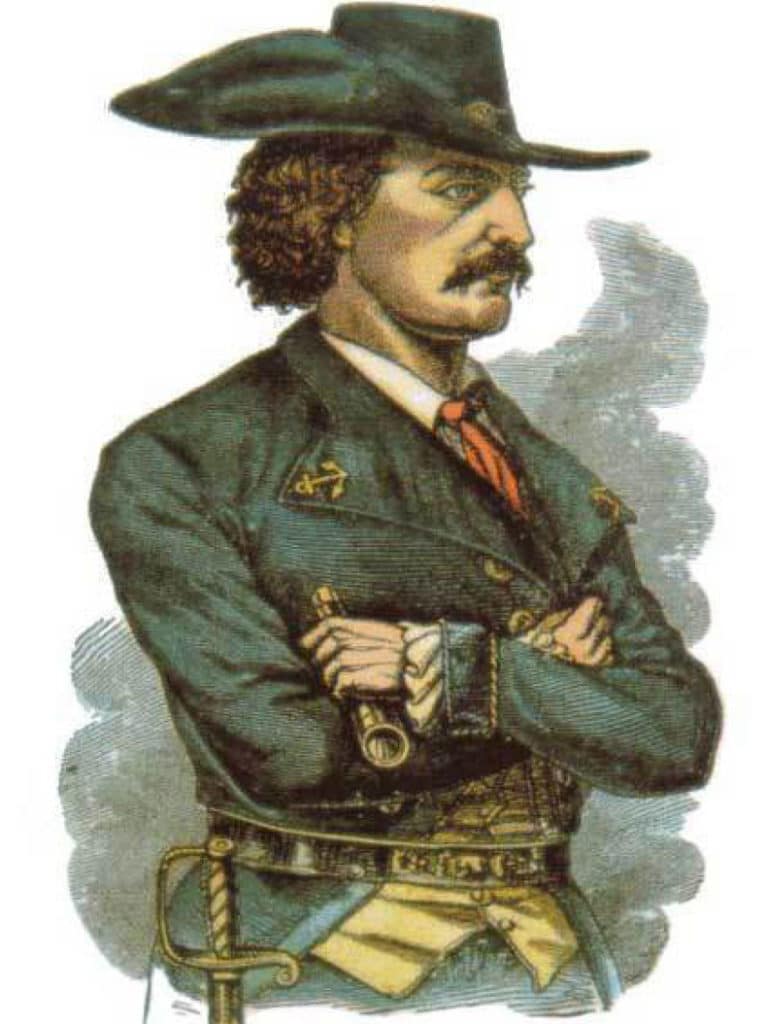

If we could go back half a century, virtually every American adult would be familiar with the name Jean Lafitte and would know, at the very least, that he had been a pirate and had played a part in the Battle of New Orleans.

In 1958, Yul Brynner had starred as Jean Lafitte in the popular movie The Buccaneer. This highly romanticized film depicted Lafitte as rallying his pirate mates to fight for the Americans at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. With their heroism, they manage to trounce the powerful British fleet and Army invading the Crescent City. (The film was a remake of Cecil B. DeMille’s 1938 movie The Buccaneer — another salute to Lafitte. DeMille was too weak to direct the remake, so he gave the directorial duties to his son-in-law Anthony Quinn. The Buccaneers was the only movie Quinn ever directed.)

With the Buccaneers fresh in the public’s mind, Johnny Horton released the single “The Battle of New Orleans” in 1959. It reached No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and won the Grammy for Best Country and Western Recording in 1960. Although the song’s lyrics don’t mention Lafitte, its subject matter would have reminded most listeners of Brynner’s depiction of Lafitte.

Horton’s song was a staple of popular radio during the 1960s. I certainly would have been able to sing it from memory by the time I was 7 or 8.

Since the 1960s, references to Jean Lafitte in American culture have been all but nonexistent.

The only reason the name was still known to the country 50 years ago was that the victory at the Battle of New Orleans was one of the high points — one of the moments of collective inspiration — in American history. The U.S. had performed poorly in the War of 1812. All four of its attempts to invade Canada had been repulsed — some by Canadian armies. Worse still, the British Army had burned down the country’s young Capitol in Washington, D.C.

The Battle of New Orleans was, naturally, seen as the great U.S. victory the country had been hoping for during the war years. Thus, it wasn’t surprising that the story of the battle that went down in history became as much myth as history. The Battle of New Orleans had, in fact, no military significance. The peace treaty between the U.S. and Britain was signed before the battle began. To the degree that the battle had value, it was in buoying the spirits of discouraged Americans.

While most historians agree that Jean Lafitte and at least a few of his pirate colleagues did fight on behalf of the Americans in the battle, few, if any, believe that Lafitte played a leadership role in the battle.

SWLA’s Lafitte

One year before Yul Brynner’s Jean Lafitte appeared on the big screen, a group in Lake Charles organized a festival celebrating aspects of Lafitte’s career that hadn’t been addressed to any great degree in the film The Buccaneers.

Lafitte liked a good fight and wasn’t afraid of law enforcement. As the story goes, he saved up a formidable pirate’s treasures that he hid somewhere in the waters of Southwest Louisiana.

This popular story is also about half fact, half myth. It is certainly true that Lafitte did some trading on the beach in front of what’s now called Shell Beach Drive. He was a good friend of the namesake of Lake Charles — Charles Sallier — and liked to visit at the cabin on the beach where Sallier lived with his family at a time when the site of the future Lake Charles was just a widely distributed collection of a few waterside cabins and shacks.

Lafitte may or may not have had an affair with Sallier’s wife. In response to his suspicions of an affair, Sallier may or may not have shot his wife. Regardless of whether a shot was fired, it seems to be true Sallier jumped on his horse and rode off into the mists of forgotten history, while his wife recovered and lived a nice, long life in the couple’s lakeside cabin. Today, her resting place is a few feet from Christus St. Patrick Hospital.

It is true Lafitte loved the waterways of Southwest Louisiana — primarily because he felt they provided an effective means of evading law enforcement. Lafitte’s men didn’t mind the sweltering heat, treacherous waters and hordes of mosquitos. But law enforcement were less accepting of these conditions, and often avoided the waterways altogether.

Lafitte also found the pirogue a very efficient device for transporting contraband.

Outside Of Southwest Louisiana

Historians are extremely skeptical about the notion that Lafitte buried a treasure in Southwest Louisiana. History shows that when pirates got money, they spent it. They lived for the present; not for the McMansion coming after a few years of serious savings. They were nomadic creatures, and handled their finances accordingly.

As much as Lafitte loved Southwest Louisiana and what would come to be known as Lake Charles, he probably loved Galveston more. Lafitte worked hard to establish a pirates’ settlement in Galveston. Common sense dictates that if Lafitte had any treasure to hide, he probably would have hidden it in Galveston.

At the time of Lafitte’s enterprise, Galveston was part of Mexico, and thus free of the constraints of U.S. law. It’s thought that during the Mexican War of Independence, Lafitte hedged his bets, flying the Mexican flag but providing intelligence to the Spanish.

Although he managed to maneuver through the Mexican War, Lafitte’s Galveston community still faced serious challenges. It was hit by a hurricane. And a botched communication with a nearby Native American community kept Lafitte embroiled in a local conflict.

The day finally came when the U.S. Navy caught up with Lafitte. Navy guns and men entirely destroyed the Galveston settlement. Lafitte fled further and further south.

He’d make his last mistake when he fired on a Spanish ship off the coast of Honduras. The ship fired back and Lafitte was hit. He was buried at sea in the Gulf of Honduras on Feb. 5, 1823.

Obscure Beginnings

It’s little known that Lafitte began as a legitimate mariner. He and his brother ran ships that brought legal imports into the New Orleans Port. But the U.S. Embargo Act of 1807 made it illegal for American ships to dock at all foreign ports.

It didn’t take Jean and his mariner brother Pierre any time at all to realize that they were being cut off from some of their most profitable Caribbean imports. After a brief period, Jean and Pierre decided that the most sensible option was to create a fleet of boats that ignored the Embargo Act and traded in illegal imports — that is, contraband. They established their first base of operations in Barataria, a marsh due south of New Orleans.

History is pretty emphatic that slaves made up part of the contraband that Lafitte dealt in. Both Mexico and the U.S. were likely displeased that Lafitte used loopholes in Mexican law to transport slaves from Galveston to New Orleans by means that were illegal under U.S. law.

A Celebration Of Buried Treasure

It was the simple, popular story of Jean Lafitte as a devil-may-care, swashbuckling privateer that was the inspiration for the Contraband Days Festival that would come into being 130 years after Lafitte’s death. This is evident in promotional material that’s used for the festival today:

“Almost three centuries ago, a notorious and ruthless pirate named Jean Lafitte and his band of buccaneers were fleeing enemy ships …” The text goes on to say that “legend has it that Jean Lafitte’s favorite hideout was Contraband Bayou in Lake Charles,” and as a result, Lafitte buried his legendary treasure in Contraband Bayou and was responsible for the bayou’s name.

And the group that would build its lore around Lafitte’s legend would eventually bear the name Contraband Days.

It began in 1957, when a group of local businessmen from the Downtown Division of the Lake Charles Assoc. of Commerce — which would later become the Chamber of Commerce — formed the group Lake Charles Contraband Days, eventually known simply as “Contraband Days.” The group assigned itself “the purpose of developing a program to use Lake Charles areas in recreational and cultural activities and attract tourists.”

It opted to focus on the legend of Lafitte and his Contraband Bayou treasure as the basis of a broadly developed pirate theme.

The first Annual Contraband Days was held in June 1958. It was a one-day event, which featured a boat parade, a water ski show and boat races.

Central to that first simple celebration was the one thing that distinguishes Contraband Days from the typical county or state fair: an emphasis on water, water sports, boats, ships and those who travel on the water.

The abbreviated form of the Contraband Days Festival would run through April, 1965, when financial difficulties persuaded the event’s leaders to give it up. In March of that year, the Lake Charles Assoc. of Commerce agreed to take over the fledgling celebration. The new group’s aim was to expand the celebration from a one- or two-day event to a full-fledged festival that lasted many days.

A Burned-Out Bar On Highway 14

Almost immediately, a group was formed to promote the new, expanded Contraband Days Festival. That group was called The Buccaneers.

The name came from an old bar on Highway 14 that had burned out. The sign for the long-deserted night spot read “Buccaneer Lounge.”

As part of the first expanded Contraband Days Festival, the Buccaneers screened the 1958 Buccaneer film starring Yul Brynner as Jean Lafitte at the Arcade Theater, which was a going concern in Lake Charles at the time. The movie had never stopped being popular, and enthusiastic audiences picked up on the connection between the movie and the new festival and flocked to the theater.

In their first year, the Buccaneers also held a large celebratory party in another Lake Charles spot that’s no longer around — the Chateau Charles.

In addition to electing officers, the group began its long-standing tradition of naming one member a year as an honorary Jean Lafitte.

After their first year in action, members of the group began to wear red jackets and serve in welcoming committees that greeted important visitors to Lake Charles.

By the late 1960s, the Buccaneers were thriving. They gradually developed their local entertainment activities by dressing in pirate attire and costumes during the festival. The group’s Jean Lafitte figure of the moment led the members of the Buccaneers in a staged effort to capture the Lake Charles mayor and take over the city as a ritual for beginning the Contraband Days festival. Some Buccaneers dressed in “City Militia” attire. Armed with “real cannons,” they tried — in vain — to prevent Lafitte and his buccaneers from landing in Lake Charles.

This scenario was designed to be entertainment for both tourists and local residents. The same scenario is still played out today at the beginning of every Contraband Days Festival. And at the end of every festival, the Buccaneers withdraw from the city to seek pirate adventures in other ports of call.

Public Service

The Buccaneers perform renditions of this or other pirate scenarios at schools, conventions and so forth throughout the year. How they perform in these scenarios is dictated by the situation. When The Buccaneers “raid” a school, they might read to the young students or sit down and have lunch with them in the cafeteria. But a 9 pm “raid” at a casino will take quite a different approach.

The Buccaneers of Lake Charles provide the primary part of the festival’s pirate-themed entertainment. Members of the Buccaneers parade through the grounds in full pirate regalia at specified times during the festival.

Both during the festival and at other events during the year, they pass out beads, doubloons and other pirate paraphernalia. They stage small parades and street dances as well. The group’s ultimate purpose is always to promote the Contraband Days Festival to all and sundry.

Contraband Days is the organization that plans, organizes and budgets for the festival’s events.

Those who are interested in having the Buccaneers provide pirate-related entertainment for their group, cause or event can contact Keith Jagneaux at buccaneersoflakecharles@yahoo.com or Mark Lavergne at lakecharlesbuccaneers@yahoo.com.

Comments are closed.