By Dr. Michael Kurth

By now, pretty much everyone in Southwest Louisiana is aware that this area is on the brink of an economic boom of historic proportions: one that will transform our communities. There is so much new investment it is hard to keep up with it: the last time I looked, $62 billion was already on the books, and I hear about numbers as high as $90 billion before the boom is over.

Economists identify three sectors of business activity: the primary sector, which consists of businesses that sell their products outside of the region, bringing money into the community and creating new jobs; the secondary sector, which consists of businesses spawned to serve the primary sector; and the tertiary sector, in which businesses provide goods and services such as food, furniture, clothing, healthcare and entertainment to the general population.

Economic growth is driven by the primary sector.

In Southwest Louisiana, our primary sector activities are chemical and petrochemical production concentrated on the west side of Lake Charles; manufacturing and transportation centered at Chennault International Airport, our ports, and along the ship channel; tourism and casino gaming; agriculture and ranching, forestry and paper products north of I-10; and the army base at Fort Polk.

The impact of these primary industries on our overall economy depends on the activity they stimulate in the secondary and tertiary sectors, known as the “multiplier effect.” For example, chemical and petrochemical plants generally pay high wages and purchase many services from local companies. Thus, they have very large multipliers (each direct job may spawn five or six additional jobs in the secondary and tertiary sectors). Casinos and agriculture, on the other hand, tend to have small multiplier effects.

All our primary industries are now doing well, but the petrochemical industry is the epicenter of the coming boom. While President Obama was promising to make the U.S. energy-independent and create millions of jobs with green energy programs, hydrofracking was turning the energy industry upside down by opening access to vast amounts of oil and natural gas trapped beneath shale deposits in North Dakota and our own backyard.

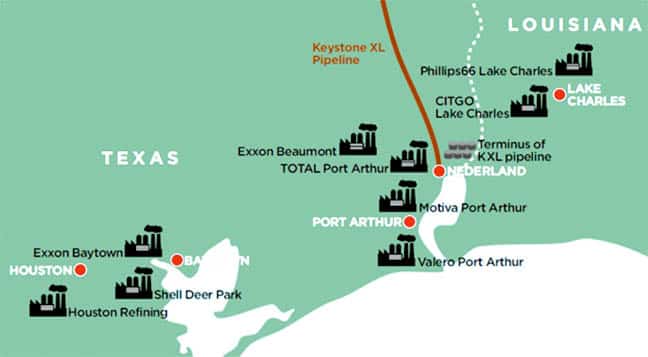

We have two major oil refineries in Southwest Louisiana: Citgo and Phillips66. Both are optimized for refining heavy sour crude obtained primarily from Mexico and Venezuela. If the last leg of the Keystone Pipeline is ever approved, it will bring oil from the Bakken field in North Dakota to our Gulf Coast refineries, including Citgo and Phillips66, allowing them to increase production and export more of their products and by-products to energy-hungry countries around the world.

But as big as oil is here, natural gas is now even bigger. In 2008, hydrofracking unlocked vast natural gas fields near Haynesville in north Louisiana, driving the price of natural gas down from $13 per million BTU to $4 per million BTU. This made Louisiana the cheapest place in the world to obtain natural gas, and the ports on the Gulf Coast the best way to get it to an energy-hungry world.

In other words, Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas are the new Saudi Arabia, and one only has to worry about crazy Cajuns instead of radical Islamic terrorists.

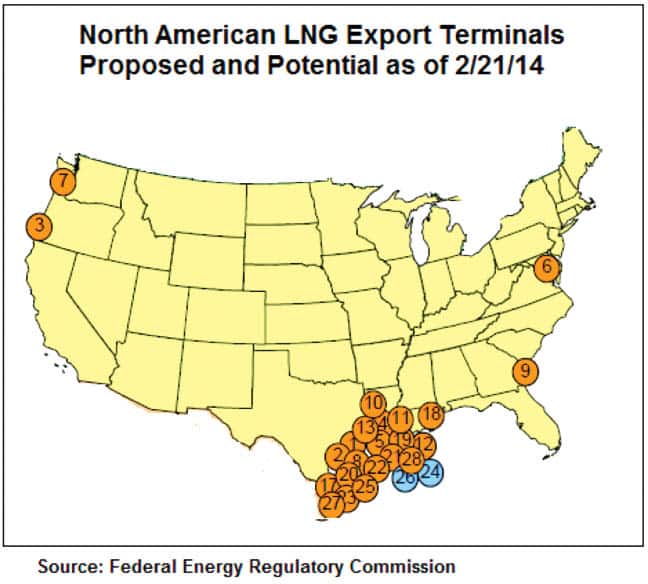

This all happened so suddenly and unexpectedly that multi-billion dollar natural gas terminals that had just been built to import natural gas now have to be reconfigured, at a cost of billions of dollars, to export natural gas. And there is a rush to build even more LNG export terminals.

The map on the next page shows the location of projects that have applied to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for export licenses, including seven located in Calcasieu and Cameron parishes.

While these facilities cost billions to build, they do not provide a large number of permanent direct jobs. They do, however, pay high wages, lots of taxes and create many jobs in the secondary and tertiary sectors.

But not everyone is happy about the natural gas boom. Although natural gas is a clean-burning fuel that can reduce greenhouse gasses, some environmentalists, and organizations like the Sierra Club, oppose its development because they claim hydrofracking damages the environment. So two years ago, the Obama administration imposed a moratorium on exporting LNG except to nations with which we have a free trade agreement, which eliminates pretty much the entire world except Canada and South America.

Recently, however, possibly in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the moratorium was lifted, and the Office of Fossil Energy of the Department of Energy (DOE/FE) approved the application of Freeport LNG in Texas, and hopefully more approvals will soon follow.

Another significant development for the future of natural gas is the widening of the Panama Canal. When it’s completed in 2015, the widening will allow large LNG tankers to pass through the canal and deliver their cargo to Asia and especially Japan, which is almost totally dependent on natural gas since it shut down its nuclear power plants following the Tsunami in 2011.

The premier natural gas project in Southwest Louisiana is Sasol’s world-scale ethane cracker and its gas-to-liquids (GTL) facility, which will make diesel fuel from natural gas. The largest single capital investment in Louisiana’s history, construction of the $7 billion ethylene cracker is scheduled to begin this summer, with construction of the GTL plant scheduled to start in 2016. There are other petrochemical projects on the books, many involving converting gas to liquids (“GTL”), but they are too numerous to go into here.

The big challenge confronting local governments is how to manage the coming boom. There will be two phases: a construction phase that will last about 10 years, peaking around 2016-17, when 10,000 to 12,000 temporary construction workers will be in the parish building these facilities. And then there will be a community-development phase that will begin in four or five years, when the new plants become operational and hire permanent employees.

During the construction phase, most of the temporary construction workers coming to Southwest Louisiana will live in trailers or self-contained “man camps,” like the one being built on Port of Lake Charles property to house 4,000 workers in dormitories that will provide parking, transportation, eating facilities, recreational activities and laundry service. We won’t see many of these workers in our restaurants and stores (most will be working, sleeping and saving their money for their families back home), so their impact on our tertiary sector will be relatively small.

Our greatest inconvenience will be traffic tie-ups caused by trucks hauling construction materials.

In the community development phase, the new plants will begin hiring 5,000-6,000 permanent employees for jobs that will pay $80,000 to $150,000 a year. About one-third will be local residents who are unemployed or under-employed, and most will be married and raising families. They will need homes, schools, shopping, recreation and medical facilities.

How much will our population increase over the next decade-and-a-half? The 5,000 to 6,000 new jobs in the primary sector could mean an additional 15,000 to 20,000 jobs in the secondary and tertiary sectors, for a total of 20,000 to 26,000 new jobs. If each job supports a household with 3.5 members and two-thirds are new residents, these figures suggest a population increase of between 46,000 and 60,000 in the next decade. This is the equivalent of Sulphur, Moss Bluff and Westlake combined.

The preparations we make today will determine what our communities will look like in the future. If we do nothing, we will end up with urban sprawl: communities with no sewer systems, above-ground cables and wires and a hodge-podge of mixed use buildings. If we take steps now to plan for the future, we can have communities with modern infrastructure, parks and green spaces, and traffic that actually flows.

Comments are closed.