In two great mid-20th century novels — Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and Robert Stone’s Hall of Mirrors — characters state that they only feel relief when they hold their lovers. These aren’t enthusiastic endorsements of romance.

In both books, romance is a safety valve one turns to for a temporary relief from the effects of what Dwight Eisenhower called “the military-industrial complex.” In Mailer’s novel, characters are harried by the clash between two mighty autocracies — Western democracy and Eastern communism — that use the overwhelming power of mass production to suck the autonomy out of life. In Stone’s novel, characters adrift in the soulless, rootless culture of Vietnam-era consumerism turn to romance in desperation.

Forty-two years after the publication of Hall of Mirrors, filmmaking brothers Brandon and Jared Drake released a film dystopia and Zach Galifianakis vehicle titled Visoneers.

This film, which Indie Express described as depicting “the digital technology de-voided, dream-deficient, mega-corporate dominated world,” shows the modern American trapped in a home life entirely devoted to consumerism or a bureaucratic work life so tedious it causes workers to explode — I mean, literally, blow up into little pieces — in the office place.

This film dystopia differs from one such as Blade Runner in that Blade Runner depicts the U.S. as it will be, say, 30 or 40 years from now, while Visoneers depicts as it will be 10 minutes from now.

While Visioneers had some real funny moments, what had me most interested in the film was my curiosity as to what was it going to propose as an alternative for the debilitating bleakness of contemporary life. I was shocked that the filmmakers came up with nothing more innovative than a romance. The protagonist (Galifianakis) strikes up a romance with a young woman living out in the country who hasn’t been corrupted by rampant consumerism. That romance is supposed to solve the problems of the world.

The Drake brothers did one thing right in respect to this flimsy means of escape: they ended the narrative with the development of the romance. There was no chance for the viewer to see what problems would arise from the romance.

Ending the story with the beginning of the big romance is one of the oldest narrative tricks there is. Any fictional story that endures over generations is sure to be loaded with conflicts. Just as surely, any romance that develops on this planet is sure to be loaded with conflicts. If a writer’s been leading up to the development of a romance during the course of a 500-page epic poem, a 1,000-page novel or a 200-page play, Lord knows he’d better stop when the big romance starts if he doesn’t want to double the length of his narrative.

Stopping when the romance starts has another big advantage: it enables the reader to do what he or she very much wants to do — believe that after this larger-than-life romance develops, it’s going to be nothing other than peaches and cream and reward the long-assailed protagonists with the relief, comfort and peace they so richly deserve after their pages of travails.

Let’s say we’ve being reading War and Peace. We’ve seen the horrible, bloody deaths in battle; the cruel betrayal of Pierre by his wife; the grating arrogance of Napoleon; the terrified families struggling to survive the evacuation from Moscow; Moscow in flames; and Pierre as a prisoner of war, crawling with lice. After all this, surely — surely — Pierre and Natasha will finally find happiness in their romance.

But, of course, we never really find out, do we? Tolstoy was already pushing it by drawing War and Peace out to a length of 1,500 pages. He certainly wasn’t going to extend it to 2,300 or 2,400 pages by describing the conflict, quarrels, disappointments, sullenness, resentment, grudging reconciliations and various other problems that developed over and over in the course of Pierre’s romance.

The great prose poet of romance — Jane Austen — almost always ends her novels with the beginning of the great romance. And when she doesn’t, as in the novel Persuasion, it’s because the great romance has become impossible. The effect is exactly the same as ending the narrative at the moment the romance begins.

A recent film, Becoming Jane, makes an interesting argument to the effect that Austen ended her narratives with the beginnings of the protagonist’s romance because Austen decided early on that she didn’t have what it takes to have a romance in real life. According to the film, romance was impossible for her. As a compensation, she wrote great stories that ended with romances that were impossible — impossible because the reader would never learn a single detail about what happened when the romance finally went beyond the stage of proposals and wedding plans and became an established state of affairs.

By ending her novels as she did, Austen avoided writing about the situation described by one of the great Victorian novelists, Margaret Oliphant, when she wrote “Life, even to a happy woman married after long patience to the man of her choice, was not the smooth road it looked, but a rough path enough cut into dangerous ruts, through which generations of men and women followed each other without ever being able to mend the way.” In the novel in which she wrote this — the 1864 work The Perpetual Curate — Oliphant avoided the challenge of writing about this troublesome state … by ending the novel at the moment the romance began.

The English Victorian novel may be the sort of literature that best presents romance as a positive, rewarding thing. It doesn’t do this by describing romance in the passionate, ecstatic terms that steam off the concluding pages of Austen novels. In the passages in which Victorian fiction paints romance in a positive light, it shows it not as an enthusiasm of the young, but as a very long-term relationship that has evolved slowly — and with difficulty — over the course of many years.

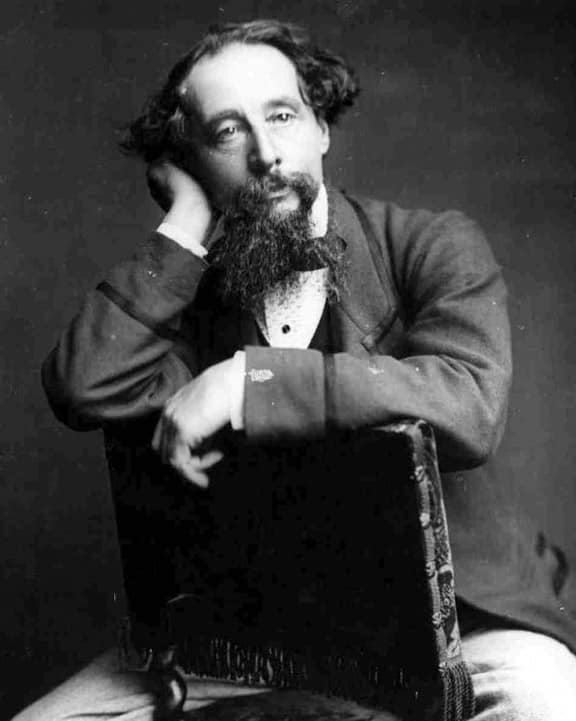

This sort of romance is seen as offering solace not in passion, but in companionship, communication (or the ability to remain silent when that is required), and, when it is helpful or sought after, the offering of advice. It’s ironic that the novelist who most frequently portrays this sort of long-term romance is Charles Dickens, who is not generally thought of as one of the passionate writers of romance.

The sedate, quiet, decades-long Victorian romance exists in the context of what we would today call the extended family. In the plot of the Victorian novel, a man or a woman returns home after a day of struggle and seeks relief in the familiarity and understanding, or at least tolerance, of the family.

In much of Victorian literature, female characters experience little other than companionship with other members of the family inside the home. Male characters who are classified as gentlemen may also find their moment-to-moment existence tied up almost entirely in home life.

In the prime of the Victorian era, the investment in home life is immense. Whatever everyday comforts are to be found are, except in extraordinary cases, to be found there.

By the end of the Victorian age, this comforting scheme of romance as a long-term relationship developing in a home that housed an extended family was undergoing a rapid disintegration. As the British aristocracy lost influence and wealth, and the middle and working class experienced robust growth, partners tended more and more to form relationships that crossed class boundaries — a kiss of death to romance. The exponential increase of industrialization, assembly line production of goods in massive quantities, ever more lavish consumerism and the breakneck speed of technological enhancement of travel and communication tore apart the sort of family portrayed in a Dickens novel. As the 20th century began, young adults found it more and more difficult to see a good rationale for staying in the family home.

The changes are crystal clear as the Victorian era and its literature draw to a close. In 1891 and 1895, Hardy’s novels Tess and Jude the Obscure depict romance as a sort of non-stop torture program for individuals severed from family ties. George Gissing’s 1897 novel The Whirlpool depicts romance as a painful losing battle against avaricious consumerism.

Gissing’s 1905 novel Will Warburton — written four years after Victoria’s death — is sympathetic towards the idea of romance. But once again, the author plays the trump card. He ends the book as the romance begins.

Comments are closed.